Dracula-Lucy’s Dream. By Plexus Polaire and Puppentheater Halle. Director Yngvild Aspeli. Dramaturges Ralf Meyer and Pauline Thimonnier. Inspired by Dracula by Bram Stoker. Theatre du Blavet, Inzinzac-Lochrist, France, March 10, 2023 and La Patinoire, Avignon, France, July 7-24, 2023. A Doll’s House. By Plexus Polaire. Directors Yngvild Aspeli and Paola Rizza. Based on A Doll’s House by Henrik Ibsen. Bayard Square, Charleville, France, September 16-17, 2023 and Théâtre Dijon Bourgogne, Dijon France March 12-20, 2024.

Yngvild Aspeli, the artistic director of French-Norwegian company Plexus Polaire, believes that puppetry can hold its own as theatre—not just as a subgenre. Her productions use the fantastical and metaphorical affordances of puppetry to explore the sometimes murky depths of human experience. The ambitious productions emerge from the deep consideration of a literary work, asking what a “physical treatment” could contribute (conversation with the author, March 13, 2024). She has developed performances from well-known works, such as Herman Melville’s Moby Dick (2020), as well as Gaute Heivoll’s Before I Burn, which became Ashes (2014), and Sara Stridsberg’s Drömfakulteten (English translation: Valerie: Or the Faculty of Dreams), which inspired Chambre Noire (2017). Here I review the company’s two most recent shows, Dracula: Lucy’s Dream (2022) and A Doll’s House (2023). Dracula, which I saw in Inzinzac-Lochrist and in Avignon in 2023, is a phantasmagoric exploration of Lucy Westenra, the nineteen-year-old at the center of Bram Stoker’s novel, largely forgotten in popular culture. A Doll’s House is an adaptation of Henrik Ibsen’s classic play, which I saw in Charleville-Mézières in 2023 and Dijon in 2024.

These densely hallucinatory, hour-long journeys reveal salient themes about the human experience in ways unique to the interplay of puppet and human. Like her other productions, the plots are transposed to visual and material dreamscapes which feature Plexus’s hallmark: meticulously fabricated, human-scale, hyper-realistic puppets animated by, through, and among the human actor-animators. The worlds that the puppets and humans build together also include masks and prostheses within a set that also transforms, alchemizing with the objects. The puppets’ realism extends to their responsive bodies, which allow the human character to animate the puppet character, physicalizing the relationship they share. So well-choreographed are the interactions that one loses a sense of who is animating whom. In fact, Aspeli uses this very question to develop the material metaphors central to the dramaturgy. The externalization of an internal state, like psychological torment, fascinates her. In Dracula, Aspeli exploits puppets’ ability to shape-shift and transgress in a play about complicity and control. In A Doll’s House, appearance and authenticity are explored through real and constructed bodies. The two productions are distinct, illuminating the breadth of strategies that she employs to explore the dark ambiguities of human nature.

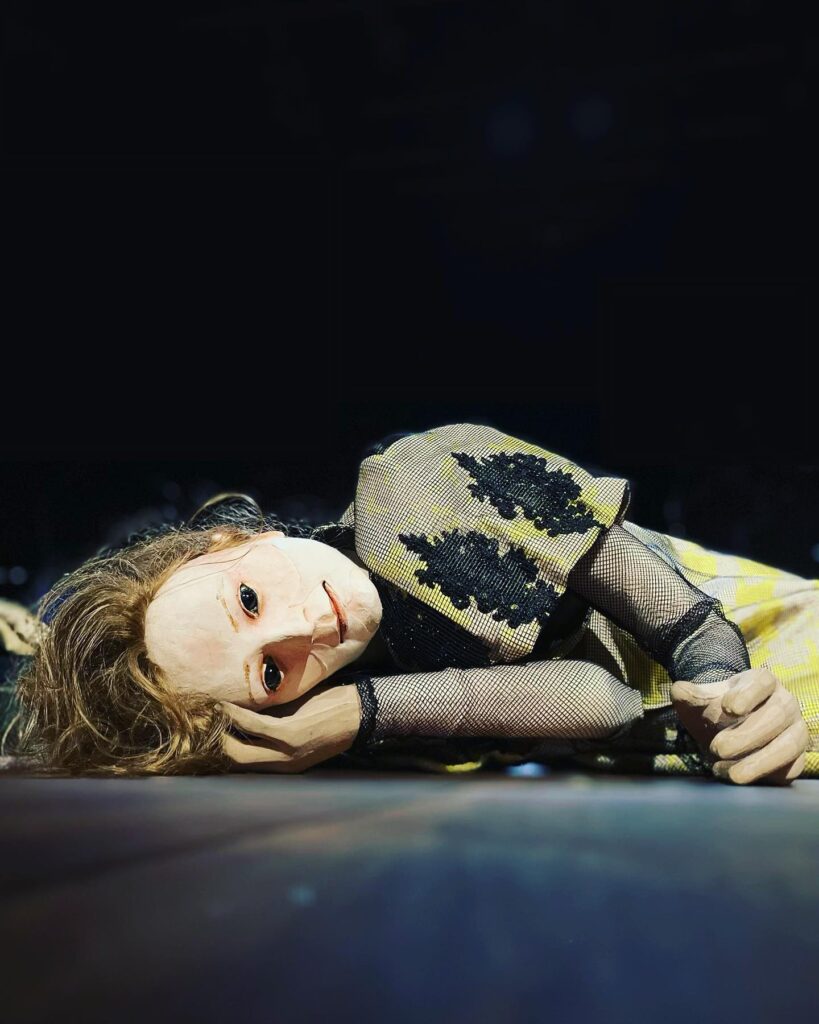

Both Dracula and A Doll’s House feature a female protagonist played by both a puppet and humans. In this way, Aspeli explains, “I give you an illusion and you believe it—then I break it” (conversation with the author, March 13, 2024). Both the illusion and the breaking of it are necessary in the shows’ explorations of transformation and the multiplicity of the self. In Dracula, Lucy’s character is fragmented––embodied by three actresses and a pale, waiflike puppet that Dracula torments and seduces. In this way, Aspeli compellingly disrupts a simple victim narrative by casting multiple Lucys, pointing to the character’s internal struggle with self-destructive desire. The puppet allows for a not-quite human version of the protagonist, her wracked body just a little too slight to be real. Her exposed joints and meticulously-sewn leather toes underscore the gap between her and the human actors. In her most pivotal moment of transformation, the puppet twists her head around and opens her impossibly wide mouth to reveal a set of fangs, hidden all along. Lucy is animated by actor/puppeteers that represent the many people who attempt, unsuccessfully, to save her from succumbing and transforming into a vampire herself. A rotating bed facilitates the switching and morphing of bodies. Interestingly, the actresses don’t look like the puppet (or each other) save for a mass of red hair and a blush-colored satin robe. This is one of many instances where Aspeli inserts a curious discrepancy for the audience to ponder.

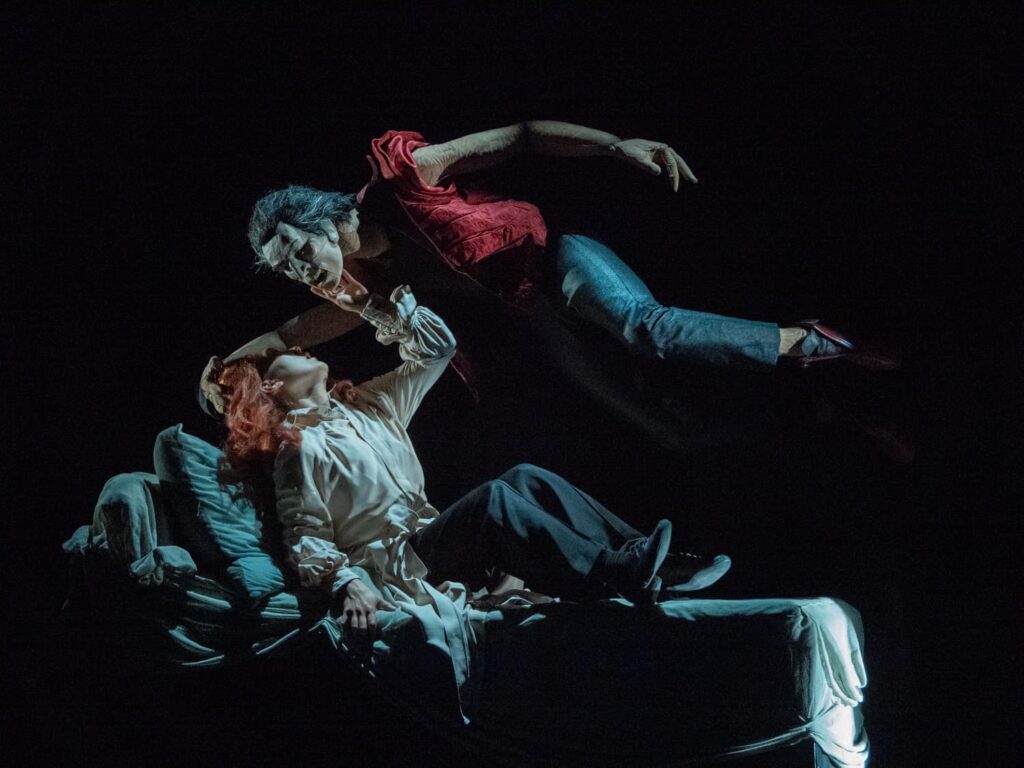

Dracula is a tall puppet with long limbs. The Lucy actresses cleverly animate him, clutching his head in their hands, bringing his fangs to their own necks and his hands to their pelvises, writhing in ecstasy. These erotic pairings follow rules: puppets don’t act upon puppets and humans don’t act upon humans. Rather, the humans seduce and are seduced by puppets, touching, caressing, groping, and biting. There are ontological reasons for this; these are fantasies and terrors produced (animated) by Lucy herself. The ambiguity characteristic of the Gothic heroine requires that she participate in her own demise. Dracula’s penetration into Lucy’s psyche is evident in the diffusion of his presence. He re-appears as a series of identical masks that the other actors (of all heights) slip on, allowing him to multiply oddly and much to Lucy’s terror. As a puppet, he defies the rules. In one moment, he shares a convincing embrace with an actress and, in the next, he levitates, fragments, and floats away—barely touching down in a pair of obscene red leather booties (that create a visual punctuation in a field of black and blush). His body parts can be animated as separate puppets––most disturbingly his torso! His disembodied head merges with spider-like creatures, provoking disgust and anxiety (and, at times, humor).

Drawing on imagery from the novel, the continuum of dog and wolf reveals the slippage between good and evil. In this suspenseful piece, Lucy pursues a playful but menacing dog whose elongated, supple neck catches the light with its glossy velour, anatomically echoing the vampiric theme. As she wanders through shifting architecture, Lucy is confronted by a terrifying creature: a gruesome mask worn upside-down on the body of a contorted puppeteer. The movable pillars and kaleidoscopic projections echo the protagonist’s fragmentation and create a gothic immensity. This is an example, too, of the subtly disorienting rotation interspersed throughout that lends an immersive and synesthetic feel, heightened by the sound of breath and heartbeat that envelop the theatre. Lucy’s vital signs locate the audience inside the puppet’s body, as we watch her attendants work to stabilize her. Almost textless, we hear “Lucy” repeated in Dracula’s rasps and the hushed voices of the frightened attendants.

Unlike Dracula, A Doll’s House is dialogue-driven. One of two actor-animators, Aspeli herself performs Nora Helmer. Jacques Lecoq trained teacher and co-director of the production, Paola Rizza collaborated on the shaping of the physicalization of this classic play. In a self-referential gesture, Aspeli moves among the puppets that populate Nora’s domestic sphere, animating them while drawing attention to the built-in relationship of control in puppetry. Nora even animates husband Torvald, who infantilizes her. In my 2024 Puppetry International review, I described what I see as Aspeli’s intentional “de-skilling” of her animation in order to make it visible as such. In this way, she uses the concept of animation in a metatheatrical way:

Aspeli (as Nora) exchanges her subtle touch for intentional stiffness, moving about a house full of life-size dolls on stands. The glassy stares and slumped shoulders of her family and acquaintances are only disrupted when Aspeli playfully inserts her hand into the backs of their heads to move their mouths and make them speak… she is intentionally pulling back from bringing the puppets to full life. Humorously, she breaks the illusion, as she stops animating the manikin-like Mrs. Linde and picks her up. Holding her flopped over at the waist… [she] is now nothing more than a limp doll. (35)

As the plot progresses, the previously overt animation allows Aspeli to show Nora’s loss of control: she has set the audience up to share Nora’s shock and horror when a puppet suddenly speaks or moves on its own. The puppetry offers powerful visual metaphors for the breakdown of Nora’s delicate pretenses to hide her fraudulent loan (Nora’s crime and “great secret” from her husband). Her world is made more complex by the appearance of her own disheveled and hopeless-looking “double,” whom she must contend with. Simultaneously, a human Torvald also appears, played by Viktor Lukawski; the puppet husband and human wife now each have a double. As Nora the actress seeks to rid herself of the doubles, Torvald clings to the material proxies and the appearance of a respectable family, arranging his manikin-like children on the sofa. As in Dracula, there are rules for the interaction; human Torvald will not interact with human Nora—only with her puppet. At one moment, in an expression of rage, he lifts her puppet double up over his head by the throat: a surrealistic visualization of the potential of his fury. These moves, both subtle and bold, are made possible by the lifelike effigies. But despite using the visual language of the fantastical, Aspeli ultimately reveals something painful and quotidian by materializing the disconnect within many intimate relationships and the, sometimes, terrifying surge of emotions triggered by a partner.

The use of puppetry allows Aspeli to literalize (and even embellish) the animal references found in a text. In A Doll’s House, Nora can become a bird by donning a large helmet mask, alluding to many of Torvald’s pet names for her. Spiders, however, also appear as a motif. Aspeli draws on Nora’s iconic, frenzied tarantella dance, once thought to be both the cause and cure for a tarantula bite. Spider puppets of increasing size emerge from the woodwork, like the anxiety in the corners of Nora’s mind. During her feverish dance, Nora is devoured and regurgitated by an enormous spider. In blacklight transformations, she dons the spider’s head as a mask, appropriating the compellingly abject anatomy of the spider’s bulging abdomen and long legs—so unsettlingly shapely and feminine. Any animal brings additional content that must work dramaturgically. For example, the spider has folkloric and pop-culture associations with the female and the dangerous, which derive, perhaps, from the fact that many female spiders devour their mates after copulation. Nora’s assumption of the spider’s body serves as her character’s initiation into a different sort of feminine energy, signaling a transformation.

The surreal materiality offered by puppetry allows Plexus Polaire to push the envelope in A Doll’s House and Dracula, creating both an absurdly erotic gothic nightmare and a poignant depiction of the disintegration of a seemingly happy marriage. In each, we experience playful disquietude. When Aspeli takes off the Victorian dress at the end of A Doll’s House, she returns to her street clothes and the real world. She pauses at the door to look back at actor Torvald, stripped bare in his humanness, with the cherished effigies of normalcy dismembered around him. Captured in this powerful visual metaphor that concludes the wild ride of this dark puppet show are the painful negotiations within and between the self and others, the struggle for authenticity, and the destructive but generative rites of initiation. Likewise, in Dracula, it is puppetry that makes visible the paradoxes embedded in the allegory of the vampire. Lucy’s fabricated body allows the audience to inhabit her in a way not possible with a human actress. As we watch the puppet writhe, surrounded by a heartbeat, we are inside––as much as outside––her battle against the transgressive potential of her fantasies and the addictive nature of desire. Plexus Polaire’s physical treatment of the unseen forces embedded thematically in these texts materializes anxiety, arousal, torment, and despair to reveal the surreal landscape of the human interior.

Felice Amato

College of Fine Arts, Boston University

References

Amato, F. “(Of)humans and Puppets at the 2023 World Festival of Puppet Theaters in

Charleville-Mézières.” Puppetry International 55 (2024): 34-37.