Late in his life, and influenced by the isolation of the COVID-19 pandemic, the death of his wife Elka, and his frustration with the persistence of US-supported wars around the world, Bread and Puppet Theater director Peter Schumann began a new phase in his art and theatre making by creating hundreds of paintings on discarded bedsheets, and then using them in different ways in Bread and Puppet productions of the early 2020s, especially productions focused on the wars in Ukraine and Gaza. The article argues that this reflects Bread and Puppet’s continuing interest in exploring new forms, as well as its recognition of such traditional forms of painting performance as cantastoria.

John Bell is the Director of the Ballard Institute and Museum of Puppetry, and an Associate Professor of Dramatic Arts, both at the University of Connecticut. He was a company member of the Bread and Puppet Theater from 1975 to 1985, and received his Ph.D. degree in theater history at Columbia University in 1993. He is a member of Brooklyn’s Great Small Works theatre collective, and a co-founder of the Honk! Festival of Activist Street Bands. He plays trombone with the Good Trouble Brass Band of Somerville, Massachusetts.

Bread and Puppet Theater occupies an unusual place in the world of theatre. Started sixty-one years ago in New York City by Peter Schumann—a German sculptor, painter, and dancer who had arrived in the United States in 1961 with his Russian/American wife Elka and four children—the company represents an aspect of twentieth-century performance which has barely survived into the twenty-first: that of an independent, non-commercial traveling and stationary theatre which embraces social and political drama, incorporates objects, music, dance, and text in inventive ways, and centers on the impetus of a director who shapes the form and content of the work, particularly through the design of visual elements. Schumann’s recent focus on the performance possibilities of large-scale paintings as visual centerpieces of puppet shows is a dramatic, late-in-life innovation in form. But it is also in keeping with his vision of Bread and Puppet Theater as a constantly evolving performance medium combining objects, music, text, dance, and performers to tell stories re-presenting and commenting on the nature of contemporary social, personal, and political life.1

Bread and Puppet and 1960s US Performance

As a director-oriented activist theatre company, Bread and Puppet is a contemporary example of a theatre model which flourished in post-World War II United States culture in such ensembles as Judith Malina’s The Living Theatre, Ronnie Davis’s San Francisco Mime Troupe, Luis Váldez’s El Teatro Campesino, Miriam Colón’s Puerto Rican Traveling Theater, and Marketa Kimbrell’s New York Street Theater Caravan, but which no longer typifies live performance in the US.2 Schumann’s theatre emerged and developed in mid-1960s New York City in the company of other innovations in US performance: the Happenings movement, Off-Off Broadway theatre, and American puppetry. Schumann’s work was similar to these three different forms of late-twentieth-century performance in many ways but, as a new form of “avant-garde” political puppet theatre, it was also markedly different.

Like the Happenings movement (in which he actively participated), Schumann’s work combined performers, dancers, and artists with sculptures, paintings, and live music, in actions with abnormal dramatic structures. But unusual for that movement, Schumann specifically used puppets and masks, routinely told political stories, and rather than limit performances to galleries, lofts, and other indoor spaces, performed as needed on streets, sidewalks, playgrounds, courtyards, and parks.

Similar to Off-Off Broadway theatre, Schumann’s work often took place in alternative theatre spaces, and included political content, non-realistic texts and characters, and poetic rather than realistic dialogue. But different from Off-Off Broadway theatre, his shows regularly used choruses and narrators as central performers, particularly focused on masks and puppets as primary carriers of meaning, frequently used proscenium stages with wing-and-drop scenery and painted curtains, and (again) routinely stepped away from indoor theatres for outdoor performances in public spaces.

Similar to 1960s US puppetry, Schumann’s work was fascinated by the modern possibilities of puppets as powerful performers of stories for adult audiences, appreciated the cultural power of global puppet traditions, often utilized fairytale dramaturgy, and celebrated puppetry as a combination of multiple art forms. But different from US puppetry of the time, Bread and Puppet shows augmented traditional forms of marionette, hand puppet, and rod puppet shows by using masks of all sizes, flat cut-out puppets, and giant puppets; used radical contrasts of scale (between the miniature and the gigantic); often used large performance spaces and large companies of eight to twelve performers rather than smaller puppet stages and small companies of one to three performers; introduced such new forms of object performance as crankies and cantastorias; performed stories about social injustice and war, including an implicit critique of US political norms; and (again) performed not only on indoor and outdoor puppet stages, but also on streets, in parks, and in other public spaces with such forms as parades, circuses, and pageants. So, while intimately related to trends in late twentieth-century US performance, Bread and Puppet also created its own unique and (as it turns out) highly influential forms.3

The distinct nature of Bread and Puppet Theater productions is especially evident in Schumann’s use of paintings and graphic designs as central elements of performance, including his most recent 2020s work with bedsheet paintings. Schumann’s early interests in sculpture easily shifted into the creation of masks and puppet heads, and his interests in dance also shifted easily into the creation of mask and puppet choreographies. But his interest in painting, drawing, woodcuts, and other forms of graphic design did not so easily morph into active theatricality. His woodcut banners could be used in parades and gallery installations, and he could use his drawing skills to create long paper panoramas for crankies. Larger-scale paintings could be used as scenic backdrops and legs in proscenium-arch wing-and-drop stages, or as the bodies of giant puppets (such as Yama, the King of Hell, in The Birdcatcher in Hell [1971]). But it was not until the 2020s that Schumann’s paintings began to take center stage as active elements in Bread and Puppet productions, in a period coincident with the COVID-19 pandemic, US-funded wars in Ukraine and Gaza, the death of Schumann’s wife and long-time partner Elka Schumann, and his stark recognition of his own mortality. Supported by a dynamic, international performing company of talented, young puppeteers; the infrastructure of the Bread and Puppet Farm in Glover, Vermont; income-producing summer performances there and equally remunerative traveling shows the rest of the year; and the robust income stream of the Bread and Puppet Press, Schumann has been able to develop multiple new productions that explore the theatrical presence of the bedsheet paintings as centers of puppet-theatre action.

Bedsheet Paintings and the COVID-19 Era

From 2020 to 2023, Peter Schumann has created over 600 large-scale paintings on recycled bedsheets, many of which he has then incorporated into a series of large and small theatre productions, parades, pageants, and exhibitions. This flurry of activity continues the approach Schumann has practiced since the early 1960s: puppetry as a combination of visual arts, dance, music, and text—but it also reflects the nature of his late-in-life experience of personal loss, the COVID-19 pandemic and a deepening sense of frustration with the state of US government policies and our organized violence around the world.

Schumann approaches this project with a fury of energy unusual for an artist in their late eighties, in an almost daily practice. Working alone in a small studio next to his house in Glover, Schumann staples a clean bedsheet to the plywood studio wall, and then allows the developing movements of hand, brush, and acrylic paint on cloth to guide his emerging designs. To this writer’s unsophisticated eye, the paintings seem to emerge from a kind of stream of visual consciousness inspired by the daily news he sees and hears, as well as poetic and philosophical texts. His paintings have always reflected an expressionist style that he has made his own, as well as specific influences from such artists as the Renaissance painter Matthias Grünewald (1470-1528), whose version of Mary Magdalene’s praying hands in the Isenheim Altarpiece is refracted again and again in the bedsheet paintings. Schumann develops images of nature, modern society, and war in a strikingly colorful palette, in contrast to some earlier monochromatic modes of work focused on either black, gray, blue, brown, or red. Perhaps like a dramatist sketching out bits of dialogue for a play, Schumann uses the paintings to develop ideas and images he then develops: as themes for new productions or specific scenes in those productions; as performing objects to be used in specific scenes; and, in printed form, as the content of Bread and Puppet publications.4

The imposed isolation caused by the COVID-19 pandemic in early 2020 shut down Bread and Puppet’s public performance possibilities, and the death of Peter’s wife and partner Elka Schumann in August 2021 was a further life challenge.5 While Bread and Puppet Theater productions did continue during the pandemic (COVID-safe performances took place outdoors at the Bread and Puppet farm throughout the summers of 2020 and 2021, a time when most theatres across the US had shut down completely), Schumann found solace and energy through his painting, which he could do in safety in the relative isolation of his home studio.

As a Bread and Puppet Theater database of the bedsheet paintings reveals, early series in 2020 and 2021 addressed a familiar variety of Schumann’s ongoing concerns: rye bread, mechanized warfare, “How to Grow Tomatoes,” and the differences between “Essentialist” forces such as sunrises and “Non-Essentialist” human activities of political domination, bureaucracy, and mechanized warfare.6 As the bedsheet painting series progressed throughout 2021, Schumann began to focus on specific themes. A “Handout” series of 31 paintings included giant hands dominating landscapes or domestic scenes; these particularly made use of Grünewald’s proto-expressionist image of Mary Magdalene’s praying hands in the Crucifixion scene of the early sixteenth-century Isenheim Altarpiece, an image which Schumann had quoted as early as the 1970s in his Fourteen Stations of the Cross passion play. Other 2021 series addressed such subjects as “Obligations” (the forty paintings in that series included “Angry Obligation,” “Anti-War Obligation,” “Excellent Abnormality Obligation,” and “Mother Earth Obligation”); “Ecstatic Decrepitude” (comments on aging); “Delphinium Revolution” (in which lush images of the flowers complement hands holding red “Revolution” banners); and “Crucifixions.” A thirteen-painting series focused on Schumann’s production of Aeschylus’s play The Persians, which was developed in the summer of 2021, and performed in Vermont, Chicago, New York, and Connecticut.

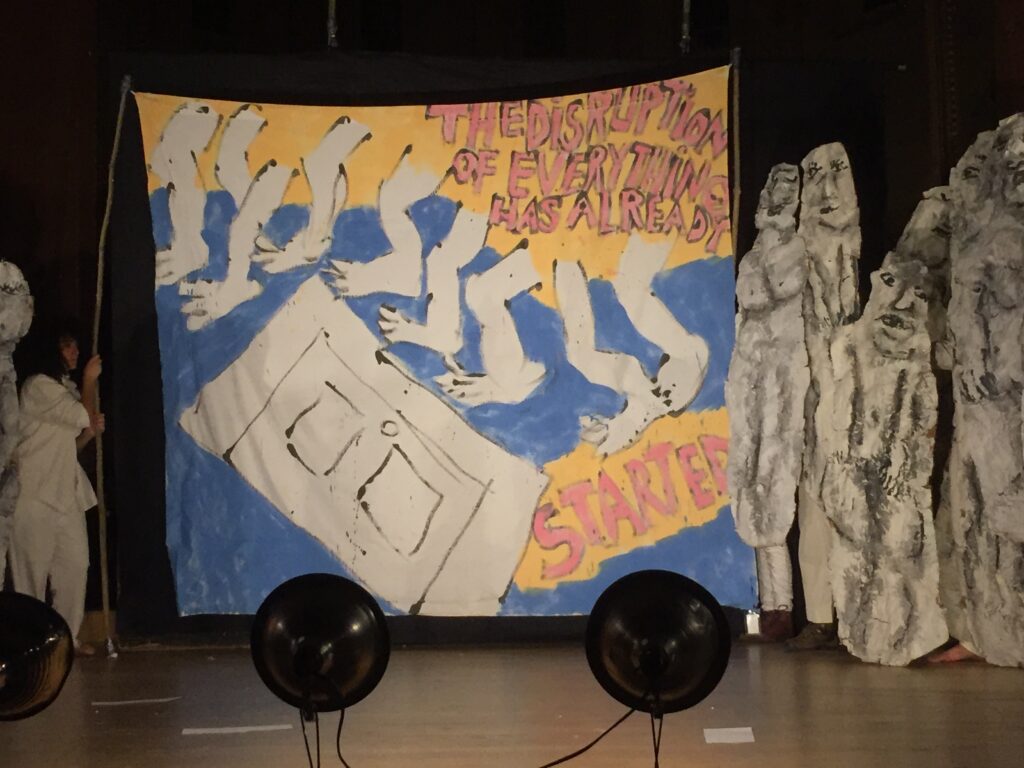

Following the Russian invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, Schumann focused more of his attention to that organized violence, from a perspective highly critical of US and NATO positions. Such banners included “Exit,” featuring a giant skeleton leaning over a white door labeled “Exit;” and “The Disruption of Everything Has Already Started,” which features nine disembodied white legs trampling over another white door. Later bedsheet series that year focused more specifically on the war in Ukraine, including three Bread Not Bombs” paintings, and forty-nine “American Apocalypse Promotion Report” paintings including one, “Strength and Determination,” featuring a strategy concept attributed to Trump administration defense analyst, Elbridge A. Colby: “An Aggressive World War Needs to Be Prepared.”7 Schumann’s suspicion of NATO and US intentions in the Ukraine War was unusual on the American left, and led to disagreements within the Bread and Puppet company and community, with audiences, and in the press.8

Schumann continued to address a variety of themes from 2022 into 2023, such as the Russian anarchist visionary Peter Kropotkin (1842-1921), who would become the focus of the 2023 touring production Inflammatory Earthling Rants (with Help from Kropotkin), as well as a theme of that summer’s main Bread and Puppet event, The Heart of the Matter Circus and Pageant; and the character “Mother Dirt”, who in Schumann’s work appears as an all-powerful force of Nature, both as the repository of the dead and the source of regenerative life. A production featuring Mother Dirt was developed as a summer 2023 indoor show in Bread and Puppet’s Paper Maché Cathedral in Glover, and Schumann later created a related Mother Dirt Mass as an ongoing community ritual performance in Glover and on tour.9 Over the summer and fall of 2023, Schumann’s painting continued to focus on Kropotkin (a less volatile subject than the immediacy of the Ukraine War); a whimsical series of fifteen “Unite” paintings riffing on Karl Marx’s “Workers of the World Unite!” slogan from the Communist Manifesto (Schumann’s variations included “Dust of the World Unite,” “Storms of the World Unite Against Stupid Capitalism,” and “Peepers and Poopers of the World Unite Against the Real Shit”); and twenty-five “Heart of the Matter” paintings, a series featuring bright red hearts in various situations (on a ladder, broken in two, as the torsos of humans, in the palms of hands, etc.). By early October, a series of twenty-three “Diptych” banners took on an almost formal tone, as Schumann experimented with the horizontal breadth of two sheets side by side, and a limited gray, black, and white palette.

Then came the October 7 Hamas attacks from Gaza on Israeli civilians and soldiers, and Israel’s crushing response, not only against Palestinian combatants, but also thousands of Palestinian civilians, and aerial bombardment flattening two-thirds of all the structures in northern Gaza. This destruction and death, made possible in large part by United States funds, touched a deep nerve in Schumann. It is safe to say that all of Peter Schumann’s work has, in one way or another, been informed by his traumatic experiences as a child in Germany during World War II—experiencing aerial bombardment, life as a wartime refugee, and seeing the bodies of Allied soldiers washed ashore after their prison ship had been bombed by Allied planes. In November 2023, during a personal discussion of the war in Israel and Gaza, Schumann remarked with deep exasperation and frustration that ever since 1961, when he had arrived in the US, the United States had been at war somewhere around the world: in Vietnam, Central America, or the Middle East. This frustration with what he sees as the United States’ permanent state of war became palpable in his next bedsheet painting series, entitled “Genocide,” some of which he used in productions created through the end of 2023 and early 2024, including more performances of the Mother Dirt Mass in Glover, participation in street protests against the Israel-Gaza war in New England, and performances in New York City of The Idiots of the World Unite Against the Idiot System Circus and The Mother Dirt Mass.10

Bedsheet Paintings in Performance

Schumann’s bedsheet paintings are a striking accomplishment of visual art, but like other aspects of the Bread and Puppet director’s artwork, they also function as performing objects in puppet shows, workshops, and exhibitions. In addition, the bedsheet paintings seem to play a new and innovative role in Schumann’s theatre making, different from the processes he has followed in previous decades. Schumann’s drawings, paintings, and woodcuts have always been functional elements in the development of theatre productions, not only as scenic presences in those productions, but sometimes instead as two-dimensional evocations of what would become three-dimensional puppet designs, sketches of scenographic moments or choreographies, or tonal and emotional referents for particular scenes. However, in rehearsal processes building scenes for new shows, Schumann’s primary focus has typically been on how combinations of performers, masks, puppets, texts, and music can create particular scenes to function in succession to tell a complete story. The advent of the bedsheet paintings (to my mind, as a longtime observer of Bread and Puppet processes) marks a kind of shift in method, as the paintings themselves begin to appear as active elements in Bread and Puppet shows.

I wonder if this shift reflects a change in Schumann’s priority of interests, which over the years have balanced dance, mask work, puppet manipulation, music, texts, and different scales and structures of performance (street shows, pageants, circuses, proscenium stages, parades, operas, masses)? As a dancer in his 80s, Schumann might have found it harder to embody the kinds of movement he invented in his 30s; as a sculptor, it might be that working with loads of heavy clay is more of a chore than it used to be. Working now with companies of young, talented puppeteers sixty years or so younger than him is probably more challenging than dynamics at play in the 1960s and 70s, when his collaborators were his own age, or only a decade or two younger. Perhaps the option of quiet, solitary art work with brushes, paint, and blank bedsheets simply makes sense at this time of life?

Whatever the reasons, this period of bedsheet painting has also helped create a particular period in Schumann’s theatre work, one that foregrounds the possibilities of paintings as performing objects. In what follows I would like to look at five of the different ways that bedsheet paintings have performed in Bread and Puppet productions from 2021 to 2023, as content-defining backdrops; cantastoria images; narrated centerpieces of exhibitions; text and character sources; and kinetic, puppet-like actants in collaboration with performers.

Paintings as Puppet Show Backdrops

In the summer of 2021, as part of Bread and Puppet’s weekly Domestic Resurrection Circus and Pageant outdoor performances, company members Joshua Krugman and Torri-Lynn Francis created Palestine, a pre-Circus sideshow (one of many performed simultaneously) about the history of Palestine. The show used bedsheet #25 from Peter Schumann’s “Handout” series, which features a set of clasped hands flanked by two rearing horses, looming over a black-and-white perspective image of a room with a table, four chairs, and three windows. After the backdrop was raised from the ground on two pulleys, Krugman (in a white Washerwoman mask and costume) silently represented Palestine, while Francis recited facts about Palestine’s history and quotations from Palestinian writers, and manipulated a number of different objects, including a chair, a basket, and a bouquet of flowers. According to Francis, while she and Krugman chose bedsheet #25 “sort of randomly,” she felt its design influenced their show. She writes that “the chair and movements felt inspired by what the images were in the painting and the colors [of] the white lady and white/gray combinations.”11

Brooklyn-based theatre company Boxcutter Collective was created by performers who met each other while working with Bread and Puppet Theater. While they generally write, design, and build their own productions, in 2022 they collaborated with Peter Schumann on Divinity Supply Company, a serious/comic look at the origins of laughter, inspired by Mikhail Bakhtin’s 1940 classic Rabelais and his World. Schumann contributed a number of his bedsheet paintings, as well as set designs and puppets, to the show, and Boxcutter members added their own texts, music, and movement ideas, many based on clowning and physical comedy. They performed an excerpt from the show at a puppet festival at Opus 40 sculpture park in Upstate New York in August 2023. A blue, yellow, and white bedsheet painting depicting God, according to Boxcutter Collective member Tom Cunningham, “was painted by Peter based on a text I had written, which was based on a footnote about an Egyptian creation myth in Rabelais and His World.” While the first part of the show was performed in front of a black backdrop, Schumann’s bedsheet banner was dramatically unfurled, comically announcing God’s arrival. A photo documenting that moment shows the Boxcutter performers bowing before the image “in a parody of religious ecstasy” (as Cunningham puts it) while Handel’s “Hallelujah Chorus” plays. While the painting functions as a backdrop, its dramatic arrival, and the performers’ direct response to it, as God, show the dynamic possibilities of the bedsheet painting as a stage character.12

Paintings as Cantastoria

Schumann’s bedsheet paintings have also functioned in a role more traditional for Bread and Puppet, as cantastoria images narrated by puppeteers, sometimes as elements of larger shows. The related international picture performance traditions of cantastoria (Italy), bänkelsang (Germany), par (India), parda-dari (Iran), pien (China), etoki (Japan), and wayang beber (Indonesia) all involve the performance of images through sung or spoken narration by performers who point to specific parts of the paintings during their storytelling.13 Bread and Puppet Theater’s 1971 anti-war cantastoria, Hallelujah—perhaps its most well-known adaptation of the form—includes masks, puppets, singing choruses, and texts in multiple languages, and initiated Peter Schumann’s continuing exploration of the form as a fast and direct way of storytelling through images.

As a Prologue to the 2021 Bread and Puppet production The Persians, Schumann invented “Homo Sapiens, Humanity, and the Chair,” a scene framing Aeschylus’s 472 BCE tragedy, that consisted of bedsheet paintings stapled in sequential series to two sets of wooden poles. In conjunction with a masked Homo Sapiens character (Barbara Leber) and an unmasked Humanity character (Ira Karp), the paintings were narrated as cantastoria explaining how Humanity, stuck to its Chair, “realizes its chair-sitting destiny,” but becomes unglued from the Chair (perhaps in order to engage with the world in an active rather than sedentary way) to introduce the Aeschylus play to the audience. Humanity announces that “The Persians, written by Mr. Aeschylus,” is (as Schumann wrote) “no celebration whatsoever, but instead a giant lamentation for the defeated archenemy.”14

![Figure 6. Bread and Puppet Theater company members (l. to r.: Joshua Krugman, Barbara Leber [in mask as Bob the Butcher], Amelia Castillo, Esteli Kitchen, and Joe Therrien) rehearsing a cantastoria version of a series of bedsheet paintings mounted on poles and crosspieces, for The Persians at Theater for the New City in New York City, December 2021. (Photo: John Bell)](https://pirjournal.commons.gc.cuny.edu/wp-content/blogs.dir/22962/files/2024/07/Bell-Figure-6-1024x881.jpg)

Paintings as Puppets: Inflammatory Earthling Rants

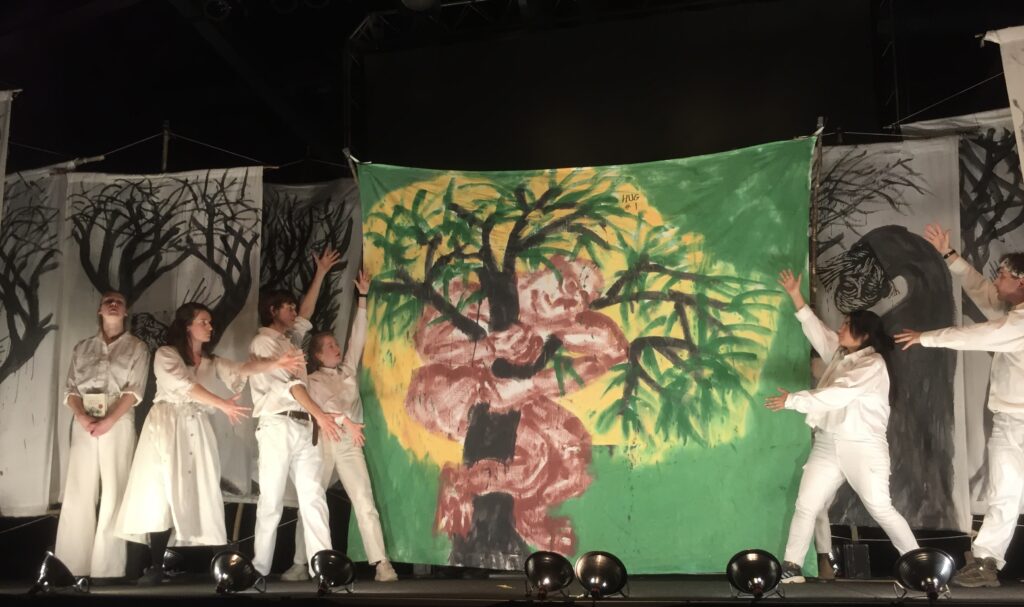

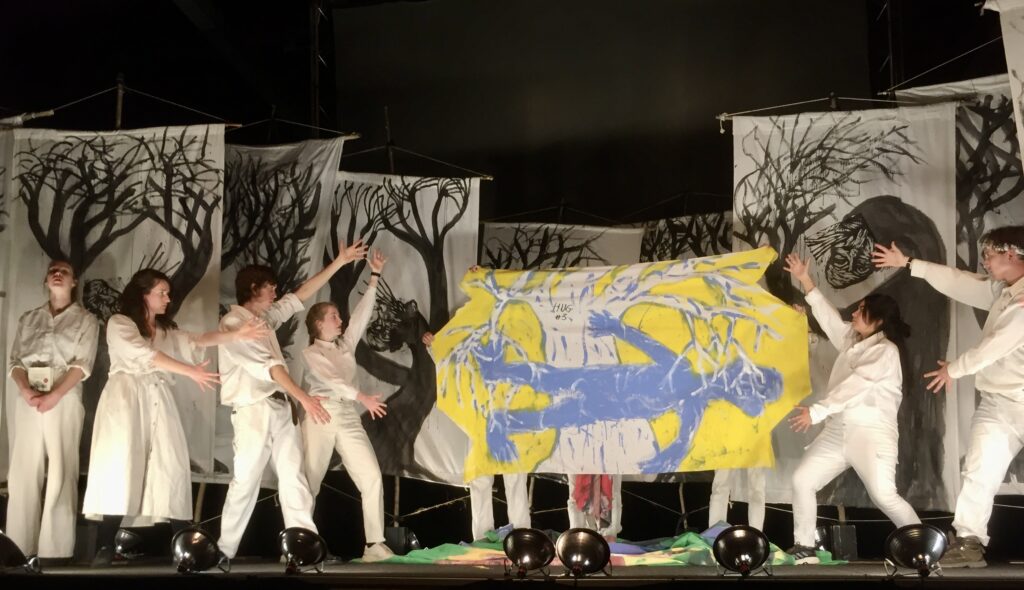

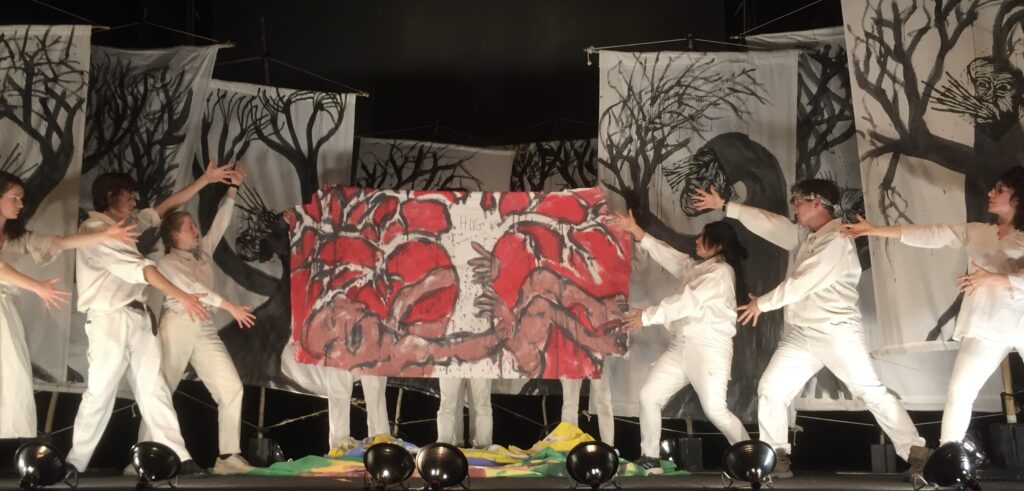

Peter Schumann’s interest in the writings of Russian anarchist Peter Kropotkin led to the 2023 creation of Inflammatory Earthling Rants [with Help from Kropotkin], which combined scenes from Kropotkin’s life and philosophical ideas about human cooperation rather than competition, with texts and images about the cooperative lives of trees, based in part on texts by Peter Wohlleben.15 While the production combined a familiar combination of performers, masks, puppets, music, and dance, there was a strong and active presence of Schumann’s graphic designs, in the large vertical black-and-white painted banners of trees, and with bedsheet paintings. One scene in the show—using Wohlleben texts, narration, and chorus choreography—marked a particularly concentrated and dynamic use of multiple bedsheets as performing objects, and merits closer attention.

The sequence begins when the first banner—a green, brown, and yellow painting of a man embracing an entire tree (#1 in Schumann’s “Tree Series”)—is brought onstage as a bundle shrouding one of the eleven white-costumed puppeteers; a second puppeteer stands behind her, thus creating a four-armed gesturing figure; the rest of the company stands left and right, facing them. After all the puppeteers execute a sequence of slow, silent hand gestures and poses, two puppeteers grasp the bunched-together painting bundle, attaching it at its top to two poles, while the company stamps the floor in rhythm and gestures to the center. When the painting is fully unfurled, a Narrator on stage right opens Wohlleben’s book and reads from it: “Why are trees such social beings?”16

As the company gestures, the banner is dropped to the floor, revealing a second banner shrouding the same four-armed figure. The chorus’s sequence of hand gestures and stamping is repeated as the second bedsheet painting is unfurled, mounted on the poles, and then made fully visible as “Tree Series” #4, a variation of the first image, with the man now climbing rather than embracing the tree, on a purple rather than green background. Again, the Narrator recites a text adapted from Wohlleben: “On its own, a tree cannot establish a consistent local climate. But together many trees create an ecosystem that moderates extremes of heat and cold, stores of water, and generates humidity. And in this protected environment, trees can live to be very old.”

This banner is also lowered to the floor, revealing another iteration of the four-armed shrouded figure, which transforms, in the next gesture and stamping sequence, to reveal a third banner, which shows the man (now blue) lying (or floating) horizontal to the vertical tree (now white), on a yellow background. The Narrator reads: “If every tree were looking out only for itself, then quite a few of them would never reach old age. Regular fatalities would result in large gaps in the tree canopy, which would make it easier for storms to get inside and uproot more trees. The heat of summer would reach the forest floor and dry it out. Every tree would suffer.”

The same movement sequence with chorus and bundled figure is repeated, for a fourth and final time, as the last banner is revealed (“Tree Series” #3): the tree and the man, with a red background this time, and the man lying on the ground, grasping the tree’s trunk. The Narrator reads again from Wohlleben’s The Hidden Life of Trees: “Every tree is valuable to the community and worth keeping around for as long as possible. And that is why even sick individuals are supported and nourished until they recover. Next time, perhaps it will be the other way round, and the supporting tree might be the one in need of assistance.”

The dynamic and transforming mutability of the paintings as performing objects is fascinating to see as an audience member. Looking at production photographs, it occurs to me that by twinning human and tree together in the bedsheet paintings, the show wants to visually underline the connection between Kropotkin as cooperative anarchist and trees as cooperative plants, so as to buttress Kropotkin’s (and Schumann’s?) belief in continuities of mutual aid among living things. In addition, the progression from man in tree to man lying on the ground brings to mind Schumann’s many meditations on death (and the human return to “Mother Dirt”), following the passing of Elka Schumann in 2021.

Chilean Puppeteer Denise Rogers Valenzuela has a first-hand perspective on the sequence, as a performer in many bedsheet-based shows over the past four years, including Inflammatory Earthling Rants. She writes that the banners “become a character—which could also be understood as a puppet, animated from within and behind.” She adds:

When the banners are unfurled and displayed like 2-D paintings, they hold the connection to the bundle character—at least for a few seconds—as a layer that it sheds from its body. Each banner shed could be seen as that which the character is, or brings to communicate with the chorus it interacts with—and, by extension, the audience. After transiting between this 3-D character, a layered lump with four arms, into a 2-D painting, it enters a third state at the end. To me, the way these banners exit via the puppeteer’s pragmatic manipulation flickers between evidencing the materiality of the paintings as sheets (which we shake like laundry before putting on the line) and animating fabric as puppets, whose mode of movement to get from A to B is undulating.17

Valenzuela’s dense interior reading of the Wohlleben scene—from her perspective as a puppeteer directly involved in the manipulation, transformation, and narration of the bedsheet paintings—points to the dramatic possibilities of such paintings as active theatrical agents, not simply backdrops against which other puppet or human activity transpires. As Valenzuela explains, the paintings transform from bundles of painted cloth, first to puppet-like characters animated by puppeteers, and finally to their more traditional cantastoria function, as two-dimensional images whose storytelling possibilities are completed with narration and chorus gesture. As a development in Schumann’s theatrical use of the bedsheet paintings since he began painting them obsessively in 2020, the Wohlebben scene in Inflammatory Earthling Rants marks a particularly complex innovation in their use.

Conclusion: Bedsheet Paintings and the Necessary Re-invention of Puppetry

An important aspect of twenty-first-century puppetry is the way its techniques continue to expand and transform. No longer limited to Western-oriented forms of marionettes, hand puppets, and rod puppets, the definition of puppetry is now enmeshed in a larger realm of “performing objects” which includes a wider range of global cultural traditions, new mechanical and digital technologies, and philosophical examinations of “things” and “matter” as actants. In the puppet world, combinations of shadow theatre with video projection and digital animation have become common; and the inclusion of crankies in puppet slams and in crankie festivals across the US also marks the increased variety of forms connected to puppetry. In the film world, adventure epics routinely combine massive and dynamic pictorial backgrounds as the green-screen contexts in which actors (often masked or combined with puppets) perform spectacular actions with mythic aspirations.18

Schumann’s own approaches to puppetry over the past sixty years have marked a particular low-tech, DIY version of this, and his recent bedsheet painting productions are a development in the picture-performance modes he has been working with since he introduced the crankie to US theatre in the 1960s, made woodcut banners theatrical actants in parades and stationary performances, and developed the cantastoria as a dynamic modern storytelling device. Schumann’s bedsheet paintings, like other aspects of his work over the past sixty years, reflect his personal, political, and philosophic concerns, as well as his changing fields of interest in terms of media (painting, sculpture, drawing, music, dance, writing); and thus are particularly challenging to analyze as theatre and performance: while one might want to consider Bread and Puppet productions by their influential technical and dramaturgical innovations, one is inevitably forced (as this article shows) to also consider the complexities of Schumann’s embrace of political theatre as an artistic mode. One realizes such complications come with the territory of puppet performance, which in global historical contexts are always also deeply connected with religion, ritual, political ideology, and the irresistible urge of puppets to criticize and comment on the status quo.

Peter Schumann’s recent productions with bedsheet paintings as consistent and dynamic centers of attention underline his sense of puppet performance as a site of constant innovation, and call to mind his repeated advice to puppeteers during the creation of new productions that “it hasn’t been invented yet.” This sense of the necessity of re-thinking and re-inventing is not only a notable achievement for an artist in his ninetieth year, but moreover a useful marker for the goals of puppetry in the twenty-first century.

Notes:

1. Photographs of most of Peter Schumann’s bedsheet paintings are documented in the following publications he has authored:

Bedsheet Mitigations. (Burlington: Fomite Press, 2020).

Handouts and Obligations . (Burlington: Fomite Press, 2021).

Declaration of Light. (Burlington: Fomite Press, 2021).

Kropotkin Says. (Burlington, Fomite Press, 2023).

Gaza Genocide Bedsheets. (Burlington: Fomite Press, 2023).

2. These activist theatre companies were later complemented by somewhat less political, but equally group-oriented “experimental” companies such as Joseph Chaikin’s Open Theatre, Richard Schechner’s The Performance Group, and such related ensembles as The Wooster Group and The Talking Band.

3. There are numerous resources about Bread and Puppet Theater, as one might expect about a sixty-year-old theatre company. See the References list below for some of these resources.

4. Most aspects of Bread and Puppet production design reflect Peter Schumann’s own specific aesthetic approach, while the actual construction of puppets, masks, and their structures and costumes is largely a group effort. The bedsheet paintings are a solo project by Schumann as painter, although the ways they are used in performance are developed in collaborative rehearsals with his puppeteer colleagues.

5. See Max Schumann, “Elka Schumann In Memoriam,” Bread and Puppet webpage (2021). https://breadandpuppet.org/elka-schumann-in memoriam#:~:text=A%20third%20stroke%20took%20Elka,and%20husband%20at%20her%20side, accessed January 13, 2024.

6. Schumann’s bedsheet paintings have also been documented in a “Bedsheet Database” spreadsheet in a Bread and Puppet Google Drive by company members Ziggy Bird Mackenzie and Raphael Royer. The database is organized by year and series, and includes titles, images, quotations, and other information. Here is a list of the series titles, by year (from 2020 through 2023) and the number of paintings comprising each series: a total of 639 paintings:

Peter Schumann’s Bedsheet Painting Series 2020-2023

2020

Non-Essentialists (12)

2021

Handout (31)

Obligations (40)

Quo Vadis (31)

Crucifixions (9)

It Is What It Is (24)

Declaration of Light (10)

Persians (13)

Hay Bale Plastic (12, painted on discarded plastic hay bale covers instead of bedsheets)

Delphinium Revolution (7)

Ecstatic Decrepitude (2)

Half-Life (12)

Chair (22)

Pillow Case Slogans (13, painted on pillow cases)

2022

Miscellaneous (13)

Finished Waiting (13)

Idolatrist Society (4)

Libations (8)

Divinity Supply (7)

Bread Not Bombs (3)

Homo Sapiens (11)

American Apocalypse Promotion Report (49)

Clouds (12)

Red Socialist Flags (15)

Tree Series (14)

Tears Series (14)

Light Series (12)

Inflammatory Earthling (8)

2023

Rescue Squad (9)

Mother Dirt (46)

Permit Denied (2)

4 Directions (4)

Absence (10)

Kropotkin (21)

Unite (15)

Miscellaneous (3)

Utopia (4)

Diptych (23)

Genocide (55)

7. Schumann’s source was apparently an article in Monthly Review: An Independent Socialist Magazine analyzing Elbridge A. Colby’s 2021 book Strategy of Denial: American Defense in an Age of Great Power. See Laurence H. Shoup, “Giving War a Chance,” Monthly Review, May 1, 2022, https://monthlyreview.org/2022/05/01/giving-war-a-chance/, accessed January 8, 2024.

8. The dynamics of political discussion within the Bread and Puppet company deserve their own analysis, which is not possible in the space of this article. While the larger Bread and Puppet community generally seems to agree on liberal-to-leftist understandings of global, national, and local affairs, the Ukraine war marked an unusual split. While traditional leftist news sources such as Democracy Now! tended to see the Russian invasion of Ukraine as unjustified and unprovoked, Peter Schumann’s views paralleled those of such groups as Code Pink and The Nation Editorial Director Katrina vanden Heuvel, who considered US and European efforts to expand NATO to include countries directly contiguous to Russia as provocatively aggressive. Within the Bread and Puppet community, these differences of perspective reflected, in part, a generational gap: Schumann’s ongoing distrust of US foreign policy has been informed by his experience of constant US warfare in Southeast Asia, Latin America, and the Middle East since he emigrated to the United States in the early 1960s. Many Bread and Puppet company members, 50 or 60 years younger than Schumann, may not have harbored such deep misgivings about NATO’s actions, while also maintaining a deeper skepticism about Russia’s motives. Back-and-forth discussions among the Bread and Puppet company (including Schumann) about Ukraine continued throughout 2022 and 2023, resulting in differently nuanced cantastoria performances, Schumann fiddle lectures, circus acts, and agreements to disagree, but did not lead to more dramatic dissension or resignations; Schumann maintained his role as the company’s director and determiner of dramaturgical content. Company feelings about the Gaza war, as that conflict developed in late 2023, appear to be much more uniform in reflecting a critique of Israel’s role in the deaths of thousands of civilians. For a left-leaning critique of Schumann’s Ukraine perspective, see Jon Kalish, “Why Bread and Puppet, the anti-war theater group, is curiously quiet about Ukraine,” VTDigger January 8, 2023. https://vtdigger.org/2023/01/08/why-bread-and-puppet-the-anti-war-theater-group-is-curiously-quiet-about-ukraine/, accessed January 8, 2024.

9. See “Mother Dirt Mass Performed each Sunday,” Bread and Puppet Theater website. https://breadandpuppet.org/paper-mache-mass, accessed January 8, 2024; and “Bread + Puppet (2023).” https://theaterforthenewcity.net/shows/bread-puppet-2023/, accessed January 8, 2024.

10. Schumann’s 2023 Gaza paintings were published as Gaza Genocide Bedsheets (see Endnote 1). For a review of the publication, see Ron Jacobs, “Gaza in Art, Anguish and Anger,” Counterpunch January 12, 2024. https://www.counterpunch.org/2024/01/12/gaza-in-art-anguish-and-anger/, accessed January 15, 2024.

11. Torri-Lynn Francis, personal communication, January 15, 2024.

12. Tom Cunningham, personal communication, January 13, 2024.

13. On the global history of picture performance and cantastoria, see Victor H. Mair, Painting and Performance: Chinese Picture Recitation and Its Indian Genesis. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 1989.

14. Bread and Puppet Theater, The Persians Chicago Version 2022, edited by John Bell and Joshua Krugman. From a Bread and Puppet Theater Google Doc: https://docs.google.com/document/d/1kW4USoipkh6LN6bEA8MNUuRrAKn9kMRc4BJqPffJ-yQ/edit, accessed January 13, 2024.

15. Texts in Inflammatory Earthling Rants (with Help from Kropotkin) were adapted from Peter Wohlleben, The Hidden Life of Trees: What They Feel, How They Communicate—Discoveries from a Secret World. Vancouver: Greystone Books, 2016.

16. The April 12, 2023 performance of Bread and Puppet’s performance of Inflammatory Earthling Rants at Judson Church in New York City is available at BREAD & PUPPET THEATER/Judson Arts, WED APRIL 12. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=R8MS5vJSS4o&t=293s, accessed January 13, 2024.

17. Denise Rogers Valenzuela, personal communication, January 13, 2024.

18. Colette Searls’s study of puppetry techniques in the Star Wars universe, A Galaxy of Things (New York: Routledge, 2023) is particularly enlightening about the ways different forms of puppet, mask, object, and digital performance function in that particular branch of exceedingly popular global culture.

References:

There are numerous references about Bread and Puppet Theater, as one might expect about a sixty-year-old theatre company. Here are a few such resources, annotated:

a) Books and Articles:

Bell, John. “The End of Our Domestic Resurrection Circus: Bread and Puppet’s Counterculture Performance in the 1990s.” TDR 43, no. 3 (Fall 1999): 62-80. A look at the development of Bread and Puppet’s annual outdoor performance event from 1970 to 1998.

Bell, John. “The Influence of Bread and Puppet Theater.” In Restaging the Sixties: Radical Theaters and Their Legacies, edited by James Harding and Cindy Rosenthal, 377-410. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2006. A review of puppeteers and artists influenced by Bread and Puppet.

Bell, John. Landscape and Desire: Bread and Puppet Pageants in the 1990s. Glover, Vermont: Bread and Puppet Press, 1997. An analysis of Peter Schumann’s giant outdoor puppet pageants.

Brecht, Stefan. Peter Schumann’s Bread and Puppet Theatre (2 vols.). London/New York: Methuen/Routledge, 1988. An extensive two-volume study of Bread and Puppet, from its beginnings to the mid-1980s.

Schumann, Peter. “What, at the End of This Century, Is the Situation of Puppets & Performing Objects?” TDR 43, no. 3 (Fall 1999): 56-61.

Schumann, Peter. A Lecture to Art Students at SUNY/Purchase New York. Glover, Vermont: Bread and Puppet Theater, 1987. A manifesto espousing non-corporate and “cheap” art making.

Schumann, Peter. The Radicality of the Puppet Theater. Glover, Vermont: Bread and Puppet

Press, 1990. A manifesto articulating central tenets of Schumann’s approach to puppetry.

Schumann, Peter. The Old Art of Puppetry in the New World Order. Glover, Vermont: Bread and Puppet Press, 1993. A fiddle-lecture manifesto about the possibilities of activist puppetry at the time of the Gulf War.

Strauss, Skye. “A Meditation on Loss.” Performing Arts Journal 45, no. 1 (January 2023): 48-51. A review of Bread and Puppet’s The Persians as performed at the 2022 Chicago International Puppet Theater Festival.

b) Films and Videos:

Halleck, DeeDee, and Griffin, George, dirs. The Meadows Green. 1974. Internet Archive, https://archive.org/details/MeadowsGreen, accessed May 16, 2024. A lyrical documentation of Bread and Puppet’s last Domestic Resurrection Circus at Goddard College’s Cate Farm, in 1974.

Farber, Jeff, dir. Brother Bread, Sister Puppet. 1992. Internet Archive, https://archive.org/details/brother_bread_sister_puppet, accessed May 16, 2024. A documentary film about Domestic Resurrection Circuses in Glover, Vermont, in the early 1990s.

Halleck, DeeDee, and Schumann, Tamar, dirs. Ah! The Hopeful Pageantry of Bread and Puppet. 2002. Internet Archive, https://archive.org/details/ah_the_hopeful_pageantry_of_bread_and_puppet, accessed May 16, 2024. Documenting many years of Bread and Puppet outdoor events in Glover, Vermont, including interviews, rehearsals, and performance footage.

Lipani, Jerome, filmmaker. Bread and Puppet YouTube channel (2014-present). https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PLCpyXonpC4fv4EBMrydmWxHnEb4j48pmO, accessed May 16, 2024. A collection of over ninety videos from 2014 to the present, documenting Bread and Puppet Theater and related performances.