Ralph Chessé: A San Francisco Century. Curated by Glen Helfand, May 16–August 18, 2024. Jewett Gallery, San Francisco Main Library, San Francisco, California

Ralphael Alexandre Chessé (“Ralph,” 1900–1991) creator of Brother Buzz, the long running children’s program that captivated San Francisco youth from 1952 to 1969, was a founding father of Bay Area puppetry. Through his company, his leadership in the Works Progress Administration (WPA) in the 1930s, and his teaching at San Francisco State College, Chessé played a key role in shaping puppetry in the region (see Bruce Chessé n.d., 2020; Ralph Chessé 1964, 1987; Fisler 2019, Comier with Foley 2022, and Richards 2023). In the Edward Gordon Craig-inflected theatre of early twentieth-century America, which held the über-marionette as more artful than the actor, Chessé championed the puppet in his permanent theatre, staging both classics (Shakespeare, Molière) and avant-garde plays (O’Neill). He became a West Coast model marionette master. Among his trainees were Lettie Schubert (1929–2006), matriarch of the San Francisco Bay Area Puppetry Guild, and his sons Dion and Bruce Chessé, stalwarts of the Northwest puppet scene. So, on May 18, 2024, as this exhibit opened at the San Francisco Public Library, Bay Area Puppet Guild members, who are all Chessé’s artistic grandchildren, great-grandchildren, and great-great grandchildren, appeared in force to hear comments by son Bruce Chessé on his father’s legacy, to get a sneak peek at new shadow work by Fred Reilly, and view this exhibit (Figure 1).

The display invited rethinking, a hallmark of our time. Someone who we Bay Area puppeteers thought of as a mainstream American twentieth-century puppet master was now re-calibrated as a Black puppeteer (descended from his Black great-grandmother) passing in a White world. The exhibit covered his long career (including his struggle in earning a living as an artist and at times working on the docks) until he finally found a home in children’s programming in the Golden Age of television (1950s to 1960s) with a show funded by Latham Foundation, an organization founded in 1918 to teach children humane treatment of animals via puppetry (Latham n.d.).

After detailing aspects of Chessé’s biography and briefly outlining the exhibition’s core focus, I will trace its design and comment on how the puppet in art exhibits is often recast from performing object to static sculpture. No doubt Chessé would have savored emphasis on this fine art valuation and celebrated his San Francisco homecoming. Still, he might be surprised to find himself being highlighted as a person of color via the audio clips by his offspring, wall text, and inclusion of family memorabilia that illuminates the exhibit.

One must understand Chessé’s biography to grasp why the curator chose to present the exhibit now—both given his quintessentially San Francisco life and current trends to redress exclusions of artists of diversity from important venues.

Ralph Chessé was born in New Orleans in a Creole family with a great grandmother who was a slave in Haiti. On an earlier census in Louisiana, the family was listed as “Negro,” but moving north and west to San Francisco by the 1920s, the light-skinned Chessés “passed” as Caucasian. Chessé had spent a few months in 1918 studying at the Chicago Academy of Fine Arts (now the Chicago Art Institute), but was largely an autodidact in art. He worked at Le Petit Theatre in New Orleans as an assistant stage designer, head of make-up, and actor in 1919; tried Hollywood and the film industry as a techie in the early 1920s; spent 1925 at the Neighborhood Playhouse in New York as scene painter and make-up man; and fully settled in San Francisco to work in theatre and puppetry by 1926, until moving to Oregon during the last years of his life.

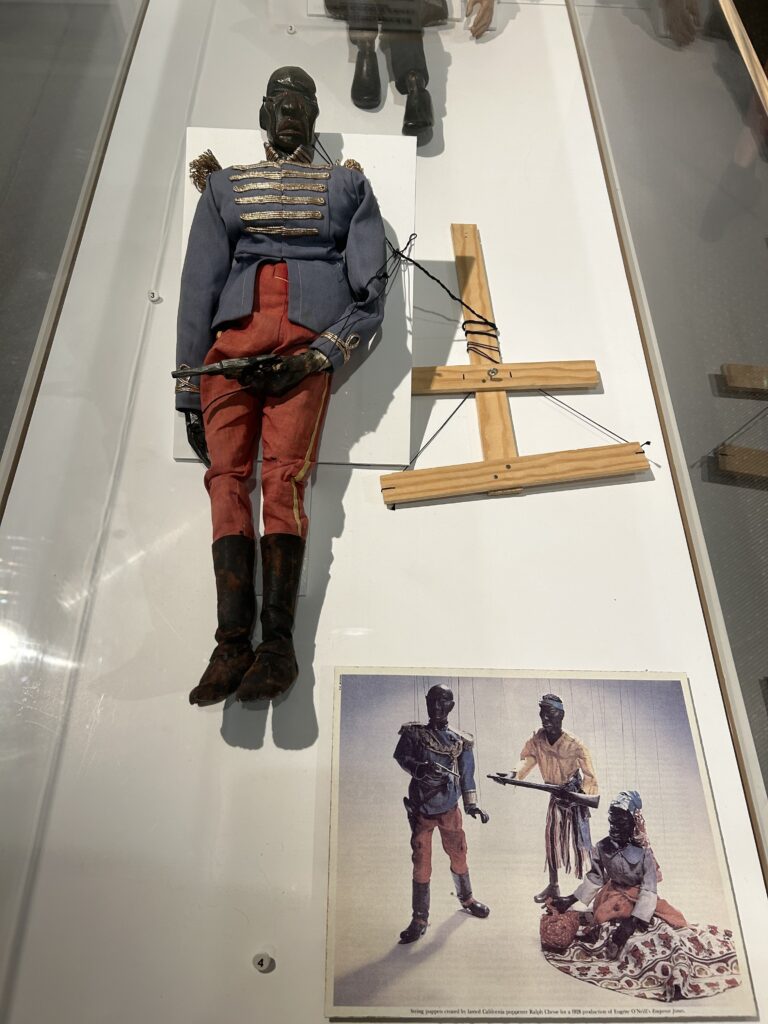

Throughout his early career, along with his passion for theatre, he painted and exhibited. But it was his mentor in San Francisco, James Blanding Sloan (1886–1975), an artist-designer-producer who, from the mid 1920s, set Chesse on the puppet path. As an aspiring actor, Chessé was seldom cast in major roles given his short height; hence, design and make-up were his entrees into theatre companies that cast him in supporting roles. Sloan’s Montgomery Street puppet theatre in San Francisco in the 1920s helped Chessé envision an artistic future: a theatre where he could play any heroes he chose since figures could trump actors. Sloan’s 1928 Heavenly Discourse by Charles Erskine Scott Wood, for example, had anatomically correct nude figures with scenes of God fondling Eve. Chessé saw puppetry could break boundaries, if not with impunity (Sloan was initially hauled in by the police), at least without jail time (the show quickly reopened to packed houses). Chessé, as a puppet master, could play his Hamlet and Macbeth or could take multiple parts in the same production (Emperor Jones and Smithers in O’Neill’s The Emperor Jones, Figure 2). At the same time, Chessé would control visual design, direct, write or adapt the script, and create the posters. The gesamtkunstwerk was possible when you were a marionette master.

During the 1930s depression, Chessé became director of the San Francisco puppetry unit of the Federal Theatre Project (FTP), and, by 1937, California State Director of the FTP puppetry program, moving temporarily for that task to Los Angeles. He developed a memorable Pinocchio for the FTP, which played at Treasure Island during the Golden Gate Exposition (1939). FTP’s public theatre model helped embed puppetry in government-funded recreation programming in the Bay Area. And Chessé’s puppets, designed for FTP, ended up with the Oakland Parks Department where Vagabond Puppet Theatre, led by his students Lettie Connell Schubert and Bruce Chessé, would, over time, flourish. During World War II, Chessé worked on the Bay Area docks, designed wallpaper, and developed puppetry in department stores like San Francisco’s Emporium). By 1949, he was teaching puppetry in adult education classes at San Francisco State College.

This exhibit aimed to present Ralph Chessé as he was—a multitalented visual artist of color, and West Coast über-marionettist, a theatre artist who controlled nearly all aspects of his presentation. Puppetry allowed him to oversee more elements than he might in actors’ theatre. Chessé’s deep connection to San Francisco was clearly presented. The path through the exhibit began and ended with paintings, giving them pride of place, and included memorabilia, photos of the artist and family, studies for his 1930s mural at Coit Tower in San Francisco, puppets, film clips of Brother Buzz, theatre posters, and production photos.

As noted, the display focused on his artistic progression from the 1920s–1980s, but rethought his work to an extent in the light of current BIPOC (Black, Indigenous, Person of Color) awareness in American culture. Prominent as one entered/exited the exhibit were his oil paintings, ranging from Black Madonna (1927, borrowed from the Oakland Museum and showing a Black mother and child) to Big Sister (1967, portraying Janis Joplin and the Holding Company, the band in which Chessé’s nephew was a musician). Such two-dimensional works began and ended the show, highlighting him as a painter. After entering the space, pictures, photos, and later puppets and playbills were laid out in rough chronology.

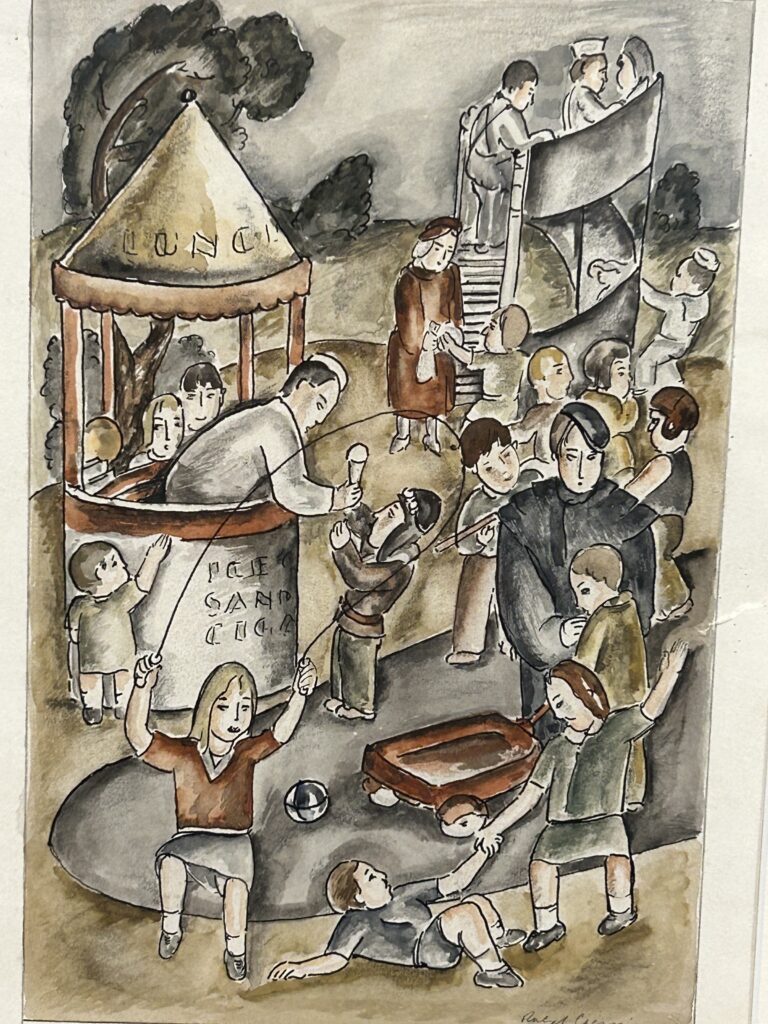

Mementos near the opening wall showed family portraits, and discussed the family’s census reports in New Orleans (where they were variously noted as M for mulatto, N for Negro, and W for White [Richards 2025]). A news clipping after Chessé’s migration to the Bay Area had a San Francisco Bay Chronicle headline of 1966 announcing that the Chessés were “The Barrymores of the Bay.” The 1927 oil painting, Black Madonna, alerted viewers to Chessé’s use of Black themes. Sketches, photos, Chessé’s book (The Marionette Actor, 1987), filled out this biographical introduction. Two dimensional sketches of his most famous puppet, Brother Buzz (Figure 3), and a photo of Chessé holding a hand puppet were the only puppet-centric aspects presented in the introductory area. The next wall introduced him as a muralist and showed his political orientation as he documented San Francisco life. Designs for his Coit Tower mural, featuring children at play and visions of San Francisco dock workers, shared traits of his1930s–1940s visual work (Figure 4). Ashcan realism, Diego Rivera murals, and early Soviet era graphics seemed apropos of this phase of his work. The exhibit highlighted the realistic depictions of lower class subjects in positive portrayals.

Finally, the viewer came to the rear of the exhibit—three walls where the puppet took over. We saw a miniature mock-up of his theatre on Merchant Street; Brother Buzz (1950s–1960s) KPIX TV clips, club pin, membership card, scripts, and, of course puppets, from both TV and puppet theatre works (Figure 4). Figures from Chessé’s most important productions (Merchant of Venice, Macbeth, The Emperor Jones, Hamlet, Salome, Don Juan, Ali Baba, etc.) were displayed. Except for the rounded, plump, friendly looking figures of the children’s TV show, one has a sense of his puppet figures being stretched and thinned. Beauty is not in realism but in the extension of the human form. Scholar Paulette Richards also noted in an email the similarity of his work to Haitian painters of the same era and the elongation of African masking/imagery which appealed to Chessé’s aesthetic sense (Richards 2025). Graphic design is in the contrast of dark with light. Exiting the exhibit, one sees late paintings: a girl in a bikini (Blue Bikini, 1960), Janis Joplin and the Holding Company (Big Sister, 1967). We are in San Francisco’s Summer of Love, with the performing arts behind us and returning to the world of two-dimensional visual art.

The exhibit organization serves as a reminder that theatre and film, however powerful, are time based, contextual things. Puppets can invade art galleries and are accessed in museum collections, but they generally do not make it there for their puppet-ness, or as active performing objects, but because they are historical markers or created by someone known for fine art. Without set, voice, music, or the specific dramatic interaction in a scene, the figure is posed—perhaps with its companion (as we see Brother Buzz floating next to his female side-kick, Busy Bee) but seldom in medias res (Figure 5). The object’s valuation is as art or historical figure. When you put a puppet in a case and buffer it with space, or juxtapose a gaunt Hamlet with an elongated Emperor Jones, you let the viewer see the figure as a separate work of art. This highlights the “style” of this artist and puppet maker. Puppets of course do appear in contemporary art galleries, but most often when the reputation of the creator as a visual artist is strong (i.e. William Kentridge). The object then will be presented for visual contemplation, beautiful but not as it might be staged in a show.

This exhibit highlighted Chessé as a visual arts master reflecting his Black identity and affinity. Ralph had Black ancestors, though this was unknown to his sons until after his death. To Caucasian puppeteers who met him in the puppet circles of the 1970s he was one of us, our elder master artist. Did his ancestry help explain why The Emperor Jones, which he staged in multiple productions, was one of his great successes? The White centricity of mainstream puppetry of the 1970s and our understanding of Chessé as a normative member of the marionette art renaissance has been washed away—we reencounter and rethink his work in an era of “Black Lives Matter.” Ralph Chessé, who we all acknowledged as a leader of twentieth-century California puppet theatre, is now seen as an artist hiding Black heritage in plain sight.[i] His oil paintings and sketches of San Francisco life open the door to the art gallery and his puppet figures follow, rising to their moment on the pedestal.

Kathy Foley

University of California, Santa Cruz

Notes

[1] Though not highlighted in information in the exhibit, Paulette Richards (2025) reports “Chessé maintained membership in the Harlem Artist’s Guild even though he never went to Harlem during the time he lived in New York. This is a strong indication that at least internally, he maintained his sense of being an artist of color.”

References

Chessé, Bruce. [n.d.]. “Ralph Chessé, 1900–1991: Painter, Sculptor, Puppeteer, Actor.” Chessé Arts.https://chessearts.com, accessed May 9, 2024.

______. 2020. “The Bruce Chessé Story.” https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gEUL04-uRRo, accessed May 9, 2024.

Chessé, Ralph. 1964. “Oral history interview of Ralph Chessé, 1964 October 22” [interview with Mary McChesney]. Smithsonian Foundation Archives of American Art https://www.aaa.si.edu/collections/interviews/oral-history-interview-ralph-chess-12664, accessed July 12, 2024.

______. 1987. The Marionette Actor. Lanham, MD: George Mason University Press.

Comer, Kellie with Kathy Foley. 2022. “Ralph Chessé. Puppetry International No. 51 [“Special Feature: PIR Review: Four Black American Puppeteers”]: 38–41, accessed May 9, 2025.

Fisler, Ben. 2019. “Black and Blackface in the Performing Object: Bullock, Chessé, Paris, the Jubilee Singers, and the Burdens of … Everything.” Living Objects: African American Puppetry Essays. https://digitalcommons.lib.uconn.edu/ballinst_catalogues/18, accessed July 12, 2024.

Latham Foundation. [n.d.]. “Brother Buzz 1950s-60s TV Series.” https://vimeo.com/showcase/5048493, accessed May 9, 2025.

Richards, Paulette. 2023. Object Performance in the Black Atlantic: The United States. NY: Routledge.

______. 2025. Personal email, May 16, 2025.