In name succession ceremonies, exhibiting excellence in traditional skills is considered a guarantee of leadership in developing and transmitting the traditional arts. Two new leaders have risen in the Youki marionette family, with differing perspectives evident in their respective celebrations. Isshi IV honored the traditional procedures while Magosaburō XIII included a new play suggesting where the winds of change may take Edo string puppetry.

Mari Boyd is professor emeritus at Sophia University, Tokyo. Researcher of modern Japanese theatre including performing objects and intercultural theatre, she is author of Japanese Contemporary Objects, Manipulators, and Actors in Performance (Tokyo: Sophia University Press, 2020).

The Edo Marionette Theatre Youkiza (Edo Ito-ayatsuri Ningyō Youkiza, hereafter Youkiza), founded in 1635, one of the oldest, active Edo string puppetry troupes in Japan, and Marionette Troupe Isshiza (Ito-ayatsuri Ningyō Isshiza, hereafter Isshiza), a branch family troupe of the Youkiza, find themselves at an important moment of transition with the 2021 investiture of Youki Kazuma[1] as Youki Magosaburō XIII (hereafter Magosaburō) (Figure 1) and of his cousin, Youki Keita, as Youki Isshi IV in 2022. Name changing is typical in traditional Edo period puppetry as in other family-based premodern performing arts like kabuki and nō. How do the two new leaders envision the relations between their 388-year heritage and the changing realities of the contemporary world and what measures are they and their collaborators taking to bridge the gap? In this context, gender representation becomes a focal area of consideration.[2]

Both cousins are already launched on leading their respective companies in the next generation of work. While the trajectories of their careers are surprisingly similar, the dynamics and decisions of the companies differ. As Isshiza’s case is more in line with conventional name changing procedures, it will be discussed first.

Isshi IV

Name Succession

Name succession in the classical performing arts and occupations that require special traditional skills, to summarize theatre historian Hattori Yukio, refers to the hereditary transference of the occupational reputation of ancestors, parents, masters, and other predecessors. For example, Youki Keita, born in 1982, debuted at age six in the traditional dance piece Renjishi (Father-Son Lion Dance) and Hal and Falstaff with his grandfather, Magosaburō X, i.e. Youki Isshi I; and later, his father’s guidance was a major factor in his preparation for the 2022 investiture.

Traditional performance rehearsals do not depend on a director in the modern sense. Junior puppeteers watch and model themselves on what their seniors do. Excellence in following traditional style or forms (kata 型) is considered one of the most important criteria of tradition, not uniqueness or innovation.

Material culture researcher Yatabe Hidemasa warns, however, “Those who try to preserve only the surface form (katachi 形) of kata will lose the spirit of creativity” (Yatabe 2007, 212). His view is that attentive training in the replication of basic movements like sitting, walking, or breathing will “naturalize” them and enable that person to connect and resonate with the external world (p. 209). This method of fostering a “naturalized” mind and body seems to have much in common with skill training in martial arts or alternative healing, such as osteopathy, chiropractic, or massage, that seek first to attain conventional alignment and functionality of bodily parts, from which a sense of centeredness can emerge. Applied to performance, this holistic method grows awareness of neutrality, centeredness, and expressivity.

Furthermore, Yatabe contends that the concept of kata “presumes both creation and decreation” (p. 212). Once a kata is established, the possibility for change arises when our desire for creativity continues— new vistas, methods, materials, to chart or illustrate the dynamic world we live in (ibid.). We will return to this point when we discuss Magosaburō’s name succession program as it takes us beyond what naming ceremonies are usually expected to do.

The hereditary transference of the leader’s title and authority includes ceremonial recognition of other changes in rank in the company. According to custom, so as not to be confused with Isshi IV, the father, at age 74, has taken a different name for himself, “Edo Dennai,” from a famous Edo period master puppeteer he respects. Furthermore, the hereditary transmission in the traditional arts is not always smooth in contemporary times as the younger generation can be reluctant to rise due to disinterest in the art. Keita was a “prodigal son,” who left the overwhelming pressures of stage life behind. But return he did, in 2000 at age eighteen, and his investiture’s celebratory production was held in Tokyo, May 2022.

One important hereditary aspect about the Youki line is that it is known for its onnagata, a male puppeteer manipulating female puppets; the “princess” role such as Yaegaki, discussed later, is considered one of the most difficult female characters to develop, requiring physical suppleness, emotional range and depth, feminine delicacy and voice, along with strength of character. The onnagata character the Youki family prefers for its name succession ceremony is Oshichi from a famous onnagata dance scene, “Hinomi yagura no dan” (Grocer’s Daughter Oshichi and the Fire Watchtower, hereafter Oshichi) excerpted from the 1773 play Date Musume Koi no Higanoko (Oshichi’s Burning Love).

Whether Isshi IV will also become an onnagata puppeteer, only time can tell. As a branch troupe, Isshiza is not obliged to produce an onnagata. The members can manipulate both male and female characters, as they are freer to continue according to their own company policy and aesthetic sensibility.

Isshi IV’s Vision: Co-existence of Tradition with Contemporary Collaboration

Isshi IV, with Dennai’s assistance, will plan the projects and programs. As the senior member of this partnership, Dennai feels that he is the conduit for the voices and wisdom of the deceased to assist Isshi IV to develop his traditional skills and aesthetics. “Enabling the past and the present to co-exist and interact while sensing keenly where the winds of the future may take them is their starting point. Without such imaginative endeavors, the art of string puppetry will not be adequately transmitted” (Isshiza 2022: 13).

Isshi IV’s Name Succession Program

A festive program of three excerpted traditional plays were performed with live chanting to three-stringed shamisen music and sound effects, plus one modern play (1890) for their succession ceremony celebrations. As is common in name succession events, the puppeteers are unhooded so that the principal name-changing performers can be easily identified.

This program was carefully arranged to display the father and son first together in a friendly Ninin Sanbasō (Double Sanbasō), a celebratory ritual dance; then apart in different plays with onnagata roles—Dennai manipulated Oshichi and Isshi IV, Princess Yaegaki; and finally together again, playing antagonists with Isshi IV as a warrior and Dennai, a female shapeshifter.

The classical Princess Yaegaki is considered a greater onnagata challenge than Oshichi. The daughter of the Uesugi clan leader and heroine of Honchō Nijūshikō (Twenty-Four Examples of Filial Piety by Chikamatsu Hanji,1766), Yaegaki has her climactic moment in the Kitsunebi (Firefox) dance scene. Her lover, Takeda Katsuyori, her father’s enemy enters the Uesugi castle in disguise, to reclaim a magical war helmet, a Takeda heirloom (Figure 4). Her father recognizes Katsuyori and secretly arranges for his murder. Fearful for her lover and herself, Yaegaki prays to the god or kami of the Suwa shrine, who sends sacred white foxes to accompany her and the magical helmet she carries as she crosses a frozen lake to save her lover from certain death. At the climax, she dances furiously as the fox spirit takes possession of her.

The finale was the Modoribashi (The Legend of the Demon Woman at Modori Bridge, 1890) by Kawatake Mokuami et al. Although “modern,” this work is packed with many exciting aspects of traditional spectacle—displays of samurai bravura, eroticism, transformation, encounters with demons, and sword fighting. When the woman figure is not reflected in the river, the warrior Tsuna realizes she may be supernatural. She transforms into a hideous demon and a lively sword fight ensues on a temple rooftop. Tsuna succeeds in slicing off one of her arms, but the maimed demon escapes by rising into the air.

Isshi IV was highly effective throughout and will surely develop rapidly with more stage experience. In the first piece, Ninin Sanbasō, he sometimes glanced at Dennai to make sure he was in sync with his senior. He also seemed more comfortable in the sword fight with the demon in Modoribashi than portraying the nuanced changes in Yaegaki’s figure during her final dance. At present, he is lean and muscular in appearance, and forceful and intense in manipulation, rather than supple and fine-tuned.

In this way, the Isshi father and son focused predominantly and successfully on displaying traditional skills and acumen congruent with what is expected at a name succession celebration. We will now proceed to his cousin Magosaburō XIII.

Magosaburō XIII

Name Succession

Magosaburō, born Kazuma in 1978, debuted at the age of six with Kotobuki-jishi (Celebration Lion Dance), and received his present title in 2021 (Figure 5). His father, born in 1943, retains his title, Magosaburō XII, and as he is also a master of magic lantern performance,[3] now uses his magic lantern title Ryōkawa Senyū III (hereafter Senyū), instead.

Like Isshi IV, Magosaburō went through a period of estrangement from the age of fifteen. In 2003, he returned home to perform puppetry again, but continued to have strained relations with his father and other relatives. He accepted the title, but how he would perform as Magosaburō was a concern for the company.

Magosaburō’s Vision: To Uphold and Perform both Traditional and Contemporary Works

Magosaburō’s vision for his company, as stated in a 2021 interview, is to ensure that the traditional repertory is maintained and transmitted. He intends to increase traditional productions during his tenure so that the two categories of traditional repertory and new productions will be represented (Youki Kazuma 2021). Knowing that some skills can only be learnt from performing traditional plays, Magosaburō intends to revive the bridge style of manipulation that employs strings two meters long, requiring the puppeteer to keep his balance with his knees bent. He knows from Senyū that he must use the whole body, especially the lumbar region, and not depend on the fingertips.

Name succession is not simply a family affair of passing on the Magosaburō name. Youkiza is very aware of their obligation to maintain and transmit the Edo string puppetry heritage as a national and Tokyo-based intangible cultural folk property, and the weight of this responsibility has sometimes led to misrepresentation.

In the Youkiza JAPAN section of the Japan Video Topics (JVT) series in 2010, the narrator introduced Youkiza’s method as follows: “Even when doing foreign or new plays, they use their traditional manipulation style” (2010). In contrast, Magosaburō made a nuanced statement, which both disclaimed and affirmed the important connection between the new and the old. “It is not necessarily the case that traditional manipulation will be used in new works, but it can be applied based on the fundamental techniques and timing of breath. Therefore, I feel that new works and tradition are closely connected” (Youki Kazuma 2021).

Youkiza honors the traditional repertory, but also devises many ways to meet the needs of the new, leading to hybrid enrichment. How performers maneuver to keep the new and the old apart and when and how they choose to fuse the two are some of the fascinating aspects of Youkiza’s art and key to understanding the company’s longevity.

Analysis of Magosaburō’s Name Succession Program

The program comprised an “odd couple” of Oshichi, the traditional onnagata dance already discussed, and Jūichiya aruiwa Hoshi no Kagayaku Yoru ni (Eleventh Night or On a Starry Night, 2020, hereafter Eleventh Night), a new adaptation of Shakespeare’s Twelfth Night, or What You Will by resident Korean playwright-director Chong Wui-sin.[4] Oshichi, the onnagata showcase the Youkiza family employs, is fifteen minutes long, while Eleventh Night is a two hour-long comic global mélange, extremely unusual for this traditional occasion. In fact, Magosaburō, Senyū, and Chong Wui-sin have audaciously led the troupe into a kata-breaking name succession program that first displayed a traditional dance of true passion and, second, undermined its onnagata with wild comedy.

In clarifying the dynamic relations between the traditional and the new, I will discuss the construction of onnagata in Oshichi and then analyze how it is undermined in the contemporary play, with Youkiza’s tacit consent. Furthermore, I will investigate how long-forgotten ambulatory styles are reestablished as the norm for men in the new work.

Edo Society, Culture, Puppets, and Onnagata

Generally, the Edo string puppetry is designed to reflect the feudal Edo culture and the social status of samurai, farmers, and townspeople, complicated by politics, wealth, and other values. The town of Edo had a kimono culture, which reinforced social status by keeping it visible through restrictions on the materials and colors of clothing.

Youkiza’s female string puppets are generally 50 to 60 centimeters tall with a torso, flexible netted midriff, limbs, but no feet (Figure 6). A full-length kimono renders Japanese female characters’ feet practically invisible; puppeteers can easily propel the legs into moving forward or even carry the puppets.

Oshichi, the ideal onnagata piece, is performed untouched by recent alteration. Manipulated by Magosaburō, she climbs up the watchtower and strikes the alarm drum to catch her lover’s attention. This scene is a choice opportunity to display traditional onnagata expertise in expressing desire, courage, female clumsiness (on a ladder), as well as desperation. The conventional portrayal of Oshichi glorifies her as a noble-minded townswoman who is committed to saving her lover.

The principle in performing quality traditional puppetry today is to honor and replicate the conventions. The traditional dance kata are respected. It is the bringing to life of the expected passionate spirit of the character that is important, without inserting novelty or implicit criticism of the formulaic gender representation.

Gender Formation in Eleventh Night

As this was Chong Wui-sin’s fourth collaboration and third play (one was a revival) with Youkiza, he was already familiar with the lead puppeteers along with the puppets’ structure and range of mobility. His agenda was to create a comical theatrical mélange through undermining stereotypes, as well as rationalizing traditional aspects no longer appropriate to the contemporary self-image of the Japanese.

In gender formation, Chong Wui-sin specified that male puppeteers take the female puppet roles and vice versa. The exceptions were father and son Magosaburōs. As both habitually perform male characters along with female ones, Magosaburō doubled as Viola/Cesario and Sebastian, except when the twins were on stage together; at such moments, Senyū played Sebastian, along with his major character, Sir Toby. The puppeteers were forbidden to adjust the pitch or tone of their voice to match their character’s gender. A guest nouveau-kabuki[5] onnagata actor, not a puppeteer, performed four male roles including the Fool and the Wise Old Man. This deliberate emphasis on “betwixt and between” characters destabilized and contributed a dreamlike or nightmarish quality to the play.

The usual ways of adjusting puppets’ movement, clothing, and character are by working on the strings, costumes, and manipulation. The Youki range in string number is from the basic seventeen to fifty. Costumes are designed carefully to conceal awkwardness of large motor movements. Olivia’s gender bending and Viola’s male disguise are examples of how ingenious or inconspicuous adjustments can make crucial differences.

Onnagata Disassembled: Lady Olivia

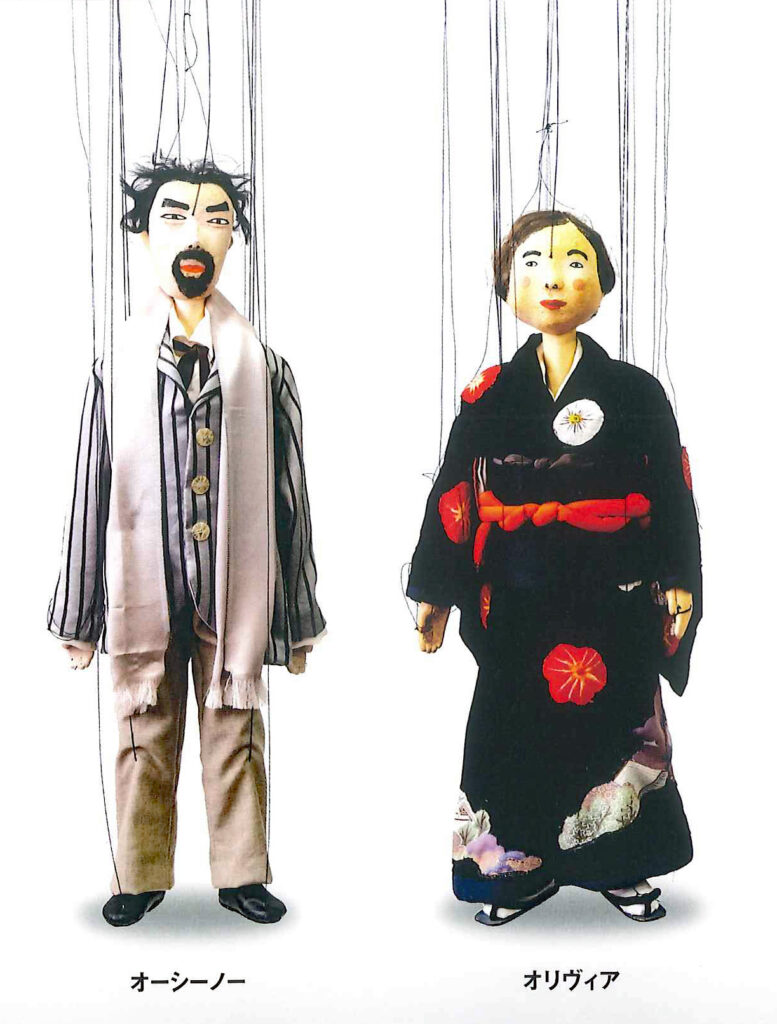

The overhauling of Lady Olivia’s gender behavior indicates that Chong Wui-sin is determined to remodel the beautiful onnagata into a comical woman energetically determined to have her way (Figure 7). Unblessed with beauty, his Olivia is otherwise equipped with the trappings of an onnagata character—good birth and wealth. In formal mourning for her deceased brother, she wears a Mori Hanae-like full-length black mourning kimono with large red and white flowers and pronged tabi socks and sandals.[6]Pursued by the infatuated Duke Orsino, she falls in love with his “beautiful-boy” page Cesario.

However, as soon as Olivia speaks, her puppeteer’s raspy male voice booms out. A closer look indicates that she has splayed feet and her mannish stride is wide enough to allow her kimono hem to open untidily and reveal layers of undergarments. An offstage question by this writer to the puppeteer in charge revealed that the Olivia puppet’s chest came from a male puppet torso, which is thicker, broader and less flexible than the usual woman puppet’s frame. Chong Wui-sin planted dissonance with the onnagata image delicately formed by Magosaburō in the first part of the program, and transformed Olivia through structural modification, costuming, and manipulation into a roaring comic character.

Male Gait: Viola in Disguise

Viola, the heroine of the play, is confronted with a gender issue from the initial shipwreck scene (Figure 8). Upon receiving artificial resuscitation from the Wise Old Man, Viola recovers from almost drowning, leaves ship to look for her lost twin brother, Sebastian, and takes a male name and disguise. Once Viola transforms into Cesario, she never appears again in female attire.

To appear more masculine, the Wise Old Man advises her to walk ganimata, which means to walk bandy-legged. In fact, there are two kinds of traditional male gaits: ganimata and nanba. Neither can be seen commonly in the urban areas of Japan anymore as Japan decided to recreate its national image as a modern and democratic state since the Meiji Restoration in 1868. In modern physical education, to meet the major objective of building modern male bodies capable of military service, military style calisthenics and marching practice were implemented in 1885 in schools nation-wide to correct posture and adopt the Western manner of walking (Yatabe 207, 49). Both gaits became associated with feudal times.

Ganimata was a half-crouched posture that was considered the default mode for male characters in Edo string puppetry. Etymologically, “gani” is a distortion of “kani” or crab and “mata” which means crotch or groin. This style could include standing with legs splayed so as to look strong. Also, allowing the kimono to open out, as Olivia sometimes does, and to reveal the sandals and lower ends of the loin cloth, is standard for male characters in comedy. In Eleventh Night, as the puppets are standing more upright than traditional male puppets do, their comical grotesqueness is less obvious.

When the key word ganimata comes from a reliable character, a clear cultural signal is sent to the twenty-first century Japanese audience. Ganimata may appall them as excessive bad taste, but in the social context of Eleventh Night, it puts Viola as Cesario on the correct course to mingle with the powerful men in the feudal society of Illyria. Furthermore, this dramaturgical maneuver enables the puppeteers to justify the traditional manipulation without modification.

The nanba walk is said to consist of a wide-stride where the arm, leg, and shoulder on the same side appear to swing simultaneously. The Japanese characters for nanba used to be 難波, a popular area in Osaka city, or 難場, literally a difficult place or situation. Considered a fast way to walk for premodern messengers, or an impressive way of presenting oneself, it was sometimes called “samurai walk,” as it creates an air of authority, energy, and radiance. Senyū agreed, in a telephone interview (February 2023), that in Edo string puppetry nanba is also used to indicate an active attitude along with positive release of energy. He added that with small puppets, the hand and shoulder tend to be pulled along by the leg movement though the swinging can be controlled through manipulation.

One common explanation of this walk is that the kimono encourages such movement. In wearing a kimono with ample sleeves, the arms are relatively still, as you would not swing or pump your arms a great deal when you walk. In the usual Western style of walking with the opposite arm and leg moving together, the kimono will loosen as the cords and sashes loosen from the twisting of the body. Study of traditional screen paintings or ukiyo-e seems to indicate that some figures are walking in nanba, but there is yet no agreed upon theory. Today, nanba continues to be researched by sports specialists, martial arts practitioners, orthopedic therapists and the like.

Scene Samples from Archival Video Clips (See Video Resources)

The script for video clip 1: Duke Orsino’s ganimata / nanba Footwork (see text below).

Orsino orders Cesario to court Lady Olivia. Duke Orsino, madly in love with love, persuades Cesario to court Lady Olivia in his stead. Carried away by his own passion, the duke exhibits a variety of footwork together with symptoms of love sickness on an outdoor flight of stairs. For this section, the playwright’s stage directions for the speeches are in parentheses and the use of nanba and other points are indicated in brackets and in bold. Ganimata is not marked out as it is the default pattern and too numerous to indicate. Lastly, Orsino speaks in a local dialect while Cesario uses polite speech.

Eleventh Night, Act I, Scene l: 21-23 Orsino’s Residence

At Orsino’s residence. Afternoon. Orsino enters calling out for Cesario. Viola enters.

VIOLA: I am at your service, my lord.

ORSINO: Oh no, I am a goner. This love sickness is driving me crazy, Cesario. You know everything about me. I have shown you the book of my heart’s secrets. Is that not so? (Viola nods.)

ORSINO: Now listen, Go to my lady’s residence right now. Even if you are denied entry, [nanba steps] stand by the gate until you receive permission to present your message directly to her. Even if your legs grow roots, you must not leave. Now go.

VIOLA: But the rumor is that she is in deep mourning, so she would not allow me an interview.

ORSINO: Be clamorous. Make noise! Raise a commotion. Make noise! Cast aside your good manners. Make noise! Go tell her of my love. This is an order.

VIOLA: If I am granted an interview, what then?

ORSINO: Confide my burning passion to her. With my true heart as love’s bittersweet weapon, bring down her defenses. She is bound to listen when she hears words of love from your sweet lips.

VIOLA: I think not, my noble lord.

ORSINO: Of course [nanba] she will. If a burly servant sweet-talked her, she would turn away. [nanba] But if you, with your glowing red lips, deep eyes, the exquisite curve of your neck, [nanba] your delicate voice that is just like a young girl’s … Even I want to hug you tight. (Orsino falls on top of Cesario and kisses him by mistake.)

VIOLA: …

ORSINO: Lady Olivia will want to meet you. I’m sure of it. You are the right one for this task. If all goes well, [nanba] you will live as freely as your lord and call his fortunes your own. Get to it!

VIOLA: I will do my best to woo your lady.

ORSINO: [Nanba] That’s the spirit. (Orsino exits.)

(Chong 2022, 21-23, all translations by author)

Coming down the steps, Orsino seems to use a heavy nanba stride appropriate for an aristocrat; his nanba is more in the leg and shoulder than the arm, which is not always engaged. He also goose steps, skips along, drags one leg, does an anime-like walk forwards while throwing his weight backwards. He sits girly style (onnazuwari) with knees touching and calves sticking out sideways. No cross-legged sitting is included due to the extra time it takes to get into that position. (Senyū III 2023) Once on ground level, Orsino takes a couple of nanba steps, before exiting. This large variety of footwork illustrates Orsino’s mood swings and enriches the viewing experience for the audience.

The script for video clip 2: The Undermining of Onnagata through Comicality—How Cesario Fares on his Courting Errand (see translation below).

The Fool mediates between Cesario and Olivia while Cesario courts her for Duke Orsino. Uninterested in Orsino, Olivia wants Cesario to call her by her name without honorifics. Olivia and the Fool speak in a dialect and Cesario, in heightened poetic language. Stage directions in the speeches are in parentheses.

Act I Scene 4: 30-33 At the Gate of Olivia’s Estate

FOOL: (Speaking for Olivia to Cesario.) Duke Orsino already knows what I feel. I cannot love him. I told him that a long time ago.

VIOLA: If I were consumed with burning love, suffering, and wasting away my life as Duke Orsino is, I would not understand the meaning of your rejection. I would not understand it at all.

FOOL: What are you going to do then?

VIOLA: I will build a willow cabin in front of your gate and day after day and night after night, I will call out your name. … Olivia!…(Olivia swoons.) Then you cannot feel composed unless you take pity on me.

The Fool lifts up the smitten Olivia.

VIOLA: How is your lady?

OLIVIA: Call me again.

FOOL: (To Cesario) Call her Olivia again.

VIOLA: Olivia…

Olivia swoons again. The Fool lifts her up again.

OLIVIA: Again.

FOOL: Again.

VIOLA: Olivia…

OLIVIA: Oh…

FOOL: (Writhing by Olivia’s side) Oh…

Olivia writhes in pleasure each time Viola calls her name.

OLIVIA: Louder

VIOLA: Olivia!

FOOL:(Writhes, too.) Oh… More gently.

VIOLA: Olivia.

FOOL: With love.

VIOLA: Olivia.

OLIVIA:(Writhing in pleasure) More, more. Call me again.

FOOL: (To Olivia) OLIVIA.

OLIVIA: You fool!

FOOL: Huh?

OLIVIA: Begone.

FOOL: Yes, ma’am. (Exits)

(Chong 2022, 29-39)

In this way, Magosaburō XIII’s investiture program started with traditional and contemporary performances in the same celebratory production. Youkiza assiduously replicated traditional conventions with Oshichi and then, cheerfully and chaotically, romped through Eleventh Night. Youkiza’s collaboration with Chong Wui-sin enabled them to interweave traditional ganimata and nanba gaits into Eleventh Night in a justifiable way and simultaneously disassemble the old-fashioned stereotype of onnagata and even the traditional format of the name succession celebration itself.

What about Magosaburō then? As the star of the show, he was able to display his present onnagata skills in Oshichi, but his efforts were curtailed in Eleventh Night as he was committed to performing a woman successfully conducting herself in male disguise.

Post-investiture production: Metamorphosis

Of the Youkiza productions that have followed the naming ceremony celebrations, I think Magosaburō discovered his best role in 2022 when he played Gregor Samsa in Metamorphosis. Franz Kafka’s 1915 novella is well known. A company employee awakes one morning to find himself transformed into a huge insect. His alienation from his family and employer deepens until he finally starves himself to death. The set shows the inside of the apartment with the living-dining room and Gregor’s bedroom separated by a tall, heavy door that opens and closes and a conventionally “invisible” wall.

As this was Shirai Keita’s[7] first experience in directing a marionette play, he was accommodating, learning what, if any, differences there were between directing puppets and humans. His “outside eye” input was very effective in the blocking and timing of the performance as the puppeteers were relatively unused to devising such aspects. Dramaturgically, he stayed with the main events and alienation theme of the original play. However, the dream of a picnic that is only mentioned in the original is staged in childlike images by covering the dead insect Gregor on the floor with green fabric decorated with pink and yellow flowers. In sheer delight, Gregor’s sister dances merrily on top of the green mound that hides the insect’s corpse, a danse macabre that callously celebrates the survival of the fittest.

The male gait did not arise much with this play. Furniture, ornaments, and characters partially blocked the audience’s view so that the puppets’ gait was not as exposed as in Eleventh Night, minimizing ganimata and nanba tendencies. Splayed feet stance when standing still is common among men today in many countries, making the sign functional in representing the play’s European men. At the same time, the splayed feet of the older housekeeper with a broom to do “battle with insect Gregor” was a deliberate sign of her primitive nature. All the female characters had feet and shoes: the mother wore mainly long dresses and the uniformed household help curtsied regularly adding a dance-like step into their movement.

The highlight of the play was the puppet insect (Figures 9 and 10). That Kafka did not specify the type of insect suited Tanihara Natsuko, an award-winning designer, who paints “beauty in the confluence of negative personal memories and the darkness of humanity” by using glitter, sequins, and metal powder as well as oil and acrylic (Tanihara n.d.). From her picture, the Youkiza art team created a locust-like puppet with two sets of miniature humanoid bandy legs and feet; a human face in perpetual agony on a long snake-like neck that emerges from the insect’s chest; and an insect head with red bulging eyes sitting on its shoulders. Three figures were used to illustrate the process of deterioration: the first looked young and clumsy; the second had a handle-like device attached so that it could crawl up walls and hang from the ceiling; and the last had a rotting apple half buried in its back, gray hair, and blood-stained tears flowing down its human face. Magosaburō ended Gregor’s insect life by cutting the strings. In that moment of stillness and silence Magosaburō’s enormous capacity for projecting pathos and alienation was revealed. He universalized traumatic stress and communicated it on stage.

Youkiza’s Metamorphosis is then also about rebirth for the company; Magosaburō has shown his readiness to take on the artistic leadership for the long journey ahead. Audiences including this writer responded to Gregor’s lacerated heart and Magosaburō’s ability to convert distress into a master’s art.

The Future and Conclusion

What may the future hold for these two developing leaders? As noted, Youkiza started with their traditional and contemporary fare together in the same celebratory production; the following year, they performed Metamorphosis. Now they have moved on to various performances, modern, premodern, comical and serious. Isshiza, which has an excellent track record of producing the Western historical avant-garde, such as works inspired by Antonin Artaud, dedicated almost all of their time to upgrading and displaying their traditional skills with their inherited repertory until March this year.

Concerning international collaborations, COVID-19’s deathlike grip on human health and attention has been waning, giving opportunities for the companies to vary their programming. Magosaburō, with the senior family members, has initiated a collaboration with playwright-director Chong Tse Chien of the Finger Players collective in Singapore to mount a mainstage production this December. He has already devised a contemporary string puppet version of Lafcadio Hearn’s Hōichi, the Earless (Miminashi Hōichi 1904), a well-known tale about a biwa hoshi (minstrel).

An international collaboration is also in the offing for Isshi IV’s troupe. They are scheduled to go to Oslo, Norway, this year to collaborate with director Lars Øyno at the Grusomehetens Teater company (Theatre of Cruelty), on Franz Kafka’s unfinished novel Hunter Gracchus. It will be their first contemporary collaboration since their name succession celebration.

The leaders and members have reflected on their companies’ past and future and confirmed that continuing the Edo string puppetry heritage is a worthy way to contribute to puppetry as art as well as to preserve a historical form. Magosaburō XIII’s program displayed how the principal puppeteers and collaborators have found dramaturgical ways to apply, justify, and even mock traditional aspects when creating new productions. Isshi IV’s program focused more straight forwardly on showcasing their traditional fare.

In this way, the approaches and activities of the head and branch families in their separate celebrations and post-investiture productions have offered Youki family’s traditional artistry and innovative creativity with promise of more to come and Youki fans would like to dream of one day viewing onstage Magosaburō XIII performing onnagata to Isshi IV’s male role (tachiyaku).

[1] Japanese, Korean, and Chinese names will be used in their normal order with the family name first and given name following.

[2] My discussion of the performances is based on my use of private videos in the archives of the Isshiza (2022) and Youkiza (2021). Some short clips that illustrated some of my analysis are available in a Zoom lecture I gave posted by Ballard Institute and Museum of Puppetry (2022). Some additional footage on Youkiza can be seen on YoukizaJAPAN (2012) and the URLs can be found under Video Resources in the References.

[3] Magic lantern feats, introduced to Japan in the 18th century by the Dutch, became popular entertainment in the 19th century with phantasmagoria, using rear projection format with portable lanterns. https://www.magiclanternsociety.org/about-magic-lanterns/the-magic-lantern-in-japan/, accessed 20 April 2023.

[4] For more information on Chong Wui-sin’s status as a resident Korean in Japan and his working relations with Youkiza, see Boyd 2020, 76-78. Alternate spellings are Chong Wishing, Chon Wishin, and Chong Ui-sin.

[5] Nouveau-kabuki refers mainly to Kanō Yukikazu’s all-male Hanagumi Shibai company (1987-), which fuses traditional kabuki with contemporary performance texts and styles. Kanō is a frequent collaborator with the Youkiza.

[6] Mori Hanae (1926-2022) was a noted Japanese fashion designer, active 1951-2004. Olivia is the only character to dress in kimono; the others wear various kinds of Western outfits.

[7] Shirai is director and actor at Onsen Dragon Theatre Company (Gekidan Onsen Doragon, 2010-).

References

Boyd, Mari. 2020. Japanese Contemporary Objects, Manipulators, and Actors in Performance. Tokyo, Sophia University Press.

Chong, Wui-sin. 2020. “Eleventh Night or On a Starry Night: An Adaptation of Shakespeare’s Twelfth Night” [Unpublished playscript].

Edo Marionette Theatre Youkiza [Website]. n.d. https://youkiza.jp/english, accessed 3 July 2023.

______. 2021 “Program for the Investiture of Magosaburō XIII.”

Hattori, Yukio. 1980. “Shūmei” (Name Succession). Encyclopedia Japonica 1st ed., ed. by Ooga Tetsuo. Tokyo: Shogakukan.

Marionette Troupe Isshiza [Website]. https://www.isshiza.com/english-2, accessed 12 July 2023

_____. 2022 “Program for the Investitures of Isshi IV and Edo Dennai.”

Ryōkawa Senyū III. 2023. Telephone interview by Mari Boyd, 15 February.

Shirai, Keita. 2020. “Henshin: Adaptation of Metamorphosis by Franz Kafka” [Unpublished playscript].

“Tanihara, Natsuko. n.d. Artists MEM.” https://mem-inc.jp/artists_e/tanihara_e/, accessed 24 May 2023.

Yatabe, Hidemasa. 2007. Utsukushii Nihon no Shintai (The Beautiful Japanese Body). Tokyo: Chikuma Shisho No. 638, Chikuma Shobō.

Youki Isshi. 2022. “Interviewing Youki Keita on his Upcoming Name Succession Ceremony to Isshi IV of the Marionette Troupe Isshiza and Youki Isshi III’s Name Change to Edo Dennai.” Spice Online Entertainment Magazine [Interview by Ando Mitsuo, Spice editor], May. https://spice.eplus.jp/articles/302914, accessed 24 May 2022.

Youki Kazuma. 2021. “Youki Kazuma Speaks out on Continuing the 385-year-old Tradition of the Edo Marionette Theatre Youkiza before Assuming the Title of Magosaburō XIII.” Spice Online Entertainment Magazine [Interview by Ishimaru Noriko], May. https://spice.eplus.jp/articles/286883, accessed 25 May 2022.

Video Resources

Ballard Institute and Museum of Puppetry. 2022. “Puppet Forum: ‘Topics in Japanese Puppetry.’” 6 December. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uyXwy146np8, accessed 30 May 2023. [Duke Orsino’s Ganimata/Nanba Footwork (Eleventh Night) at 35.04 and Gregor vs Housekeeper (Metamorphosis) at 41:20. See also https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uyXwy146np8&t=282s].

Edo Marionette Theatre Youkiza. 2021.Youki Magosaburō XIII Name Succession Celebrations. [Private video], accessed 25 May 2023.

Marionette Troupe Isshiza. 2022.Youki Isshi IV Name Succession and Edo Dennai Name Change Celebrations. (Japanese) [private video], accessed 24 May 2023.

YoukizaJAPAN 2012 [2010]. “Edo Period Puppet Theatre 2010/2011.” Japan Video Topics (English). https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kuwlcp2Kh_U, and https://www.youtube.com/user/youkizaJAPAN, accessed 2 June 2023. [See Youki string puppet structure at 1:26-2:33, Youkiza puppet manipulation at 3:28-4:13.]