In this article I analyze a series of performances, developed since the 1950s by Mane Bernardo and Sarah Bianchi, that uses the puppeteer’s bare hand, which led to the creation of a technique called pantomime of hands. [1] I will examine the limits of the traditional definition of puppet and the practices it encompasses, along with the notion of experimentation proposed by Bernardo, an idea marked by the tensions between traditional and modern puppet theatre. I aim to place this new technique among others that contributed to the modernization of the puppet theatre in Argentina.

Bettina Girotti holds a PhD in History and Theory of Arts from Facultad de Filosofía y Letras, Universidad de Buenos Aires (Argentina), where she is assistant professor and coordinates the Puppetry area at the Performing Arts Institute “Raúl H. Castagnino.” She is a member of the jury for the Premio Nacional de Titeres Javier Villafañe. She is the editor of Los titiriteros obreros: poesía militante sobre ruedas (2015, Eudeba) and Teatro Independiente: historia y actualidad (with Paula Ansaldo, María Fukelman, and Jimena Trombetta, 2017, Ediciones del Centro Cultural de la Cooperación).

If we do not work with the imagination for the imagination, we will miss one of the most important principles for performing puppet theater shows. (Bernardo 1963, 22)

In 1961, the Argentine puppet company, Títeres Mane Bernardo Sarah Bianchi, premiered Dicen y hacen las manos (Hands Say and Do) at Teatro Agón in the City of Buenos Aires. Unlike their previous plays, the artists set aside traditional hand puppets and, instead, used their bare hands as puppets. This premiere was the result of research, begun in 1954, into the dramatic power that the hand could acquire when forsaking the puppet. By 1961, the artistic duo had been working together for more than two decades. In 1944, Mane Bernardo[2] had been invited to organize the Teatro Nacional de Títeres (National Puppet Theatre) at the Instituto Nacional de Estudios Teatrales (National Institute of Theatre Studies), a company that Sarah Bianchi[3] had joined, initially to craft heads for puppets and paint sets, where she later would begin performing as a puppeteer. After that experience ended in 1947, the artists founded a company that they first named Teatro Libre Argentino de Títeres (Argentine Free Puppet Theatre) and which, after 1954, took the name of Títeres Mane Bernardo Sarah Bianchi.

Their research on the hand as an expressive medium progressed through a series of developments. Before shaping the technique that they named pantomima de manos (pantomime of hands), which theywould later integrate into their shows, Bernardo and Bianchi experimented with different options to break away from conventional puppet forms, such as exploring the effects of gloves or a hand wearing makeup and different forms of animating these alternative puppets. Their research is connected to Bernardo’s theoretical reflections, many of them published in different books, among which Títere: magia del teatro (Puppet: Magic of the Theatre), issued in 1963, stands out. Here, the puppeteer outlines the idea of a tiempo de lo experimental (experimental era), a preliminary theoretical framework for contemporary explorations that she would develop further in later works. According to the first definition of this concept, the history of puppetry can be organized into popular, artistic, and experimental eras; the latter would encompass dialogues between puppetry and other arts.

Pantomime of hands, which I include here in the heterogeneous constellation of puppetry techniques, puts at the forefront—back then and now—the paradoxical status of the hand in traditional puppet theatre, since, although it constitutes a fundamental element of the puppet’s movement, it generally remains hidden, either off-stage or on-stage (present, but concealed).[4]

Here, I aim to review the work with the bare hand—that is, the hand devoid of the puppet— developed by Mane Bernardo and Sarah Bianchi since the 1950s, paying special attention to the adult show Dicen y hacen las manos (Hands Say and Do), staged in 1961, 1962, and 1964 and performed entirely with this technique. To consider this novelty as part of the world of puppetry forces us to examine the limits that a traditional definition imposes on the word puppet and the practices that it encompasses, and invites us to place the pantomime of hands among those developments that contributed, with different nuances, to the modernization[5] of puppetry in Argentina. Due to their long histories, some puppets and their manipulation techniques have been presented as traditional: Western techniques, such as the hand puppet or string or rod puppets (e.g. the Sicilian pupi); and Eastern techniques, such as the wayang or Javanese shadow theatre and the Japanese bunraku, among others. New techniques, the result of diverse attempts to renew puppetry, have taken those considered as traditional as a basis for proposing new forms, new aesthetics, and new connections between the puppet and the puppeteer. My interest lies in the development of the theoretical and scenic reflections that lead us to consider the pantomime of hands as a new puppetry technique[6]. Likewise, I will recover the notion of experimentation proposed by Bernardo, central to her theoretical and artistic approach, and marked by the tensions between traditional and modern forms that puppet theatre underwent during the second half of the twentieth century.

From Hand as Motor to Hand as Character

Bernardo and Bianchi’s research into the pantomime of hands included several phases, which helped the artists improve their creations. During these investigations, they examined new elements. Later they would incorporate the pantomime in various performances, several times in combination with other puppetry techniques. The explorations carried out by Bernardo and Bianchi grew in tandem with their reflections about the relationship between the puppet and the puppeteer, especially in the case of hand puppetry, a technique used almost exclusively by these artists until they finally adopted the pantomime of hands.

In traditional hand puppet technique, the hand puppet is manipulated from below and its body is formed by the puppeteer’s hand. He or she wears the puppet’s clothes, while positioning his or her fingers in different ways to hold the head and shape the limbs. A loan takes place: whoever manipulates the puppet lends a part of his or her body to it, generally the hand, and it becomes a constitutive part of the puppet. The hand thus acquires a paradoxical status: it has a fundamental function in bringing the puppet to life, but it remains concealed. Beatriz Trastoy and Perla Zayas de Lima (1997, 119-20) describe the existence of a paradoxical relationship according to which “. . . the actor expresses himself through an object other than himself, but the link between them is so narrow, so indissoluble, that the limits are finally blurred.”

A topic that runs through twentieth-century puppetry emerges: puppetry’s definition and delimitation. Javier Villafañe (1944), in a more poetic than academic explanation, places the birth of the puppet at the moment when “. . . the first man lowered his head for the first time, in the dazzling of the first dawn and saw his shadow projected on the ground, when the rivers and lands did not yet have names” (Villafañe 1944, 74). These words bring to the fore one of the fundamental elements that reflect on Bernardo-Bianchi pantomimes: the imprint of the human body on the puppet’s body, and the consequent difficulty of establishing clear limits between them. The term “puppet,” which traditionally denotes an anthropomorphic doll similar to a human being, is put into question in the case of the pantomime of hands. Although the hand is presented as a synecdoche (as it does not lose continuity with the body), it abandons the imitation of the human figure, putting on hold any figurative obligations.

Chiara Cappelletto (2011) offers a new dimension to the object-puppet and puppeteer relation by considering this link in terms of prostheses. She uses the example of the hand puppet to illustrate her proposal. Citing the Russian puppeteer Sergei Obraztsov, she explains that, when removing a puppet’s costume and leaving the bare hand just with the head placed on one of the fingers, the character survives, but if the hand is removed, the character falls apart. From this perspective, the hand puppet would reverse the prosthesis operation: it is not a piece or an artificial device that replaces a part of the human body, but rather is a part of the human body—the hand—that completes an artificial figure—the puppet.

Obraztsov’s (1950) reflections on the relationship between the puppet and the human hand are not limited to the scene described by Cappelleto. In several passages of his book My Profession (1950), the Russian puppeteer recounts his experiences with what he termed puppet-hand (that is, the hand without the costume, but with the head located on one of the fingers) looking for a “. . . form in its own full right” (Obraztsov 1950, 186). It was not simply a question of undressing the puppet, but of achieving a synthesis: “. . . because the hand only hints at the human body, without attempting to portray its anatomical structure, the head too must only hint at a human head and not show it in anatomical detail” (Obraztsov 1950, 186). These hints are represented by two points (eyes) and stripes (nose and mouth). This state of simplicity—as Obraztsov defines it—results in a compact version of the hand puppet. This research led him to try other performative forms for the hand that did not imply disguising it, such as a dialogue between the left and the right hand in which neither of them represented a character, but were simply hands, although their gestures were exaggerated to endow each one with a distinguishable personality. Obraztsov (1950, 191) concluded that “. . . one should be responsive to this expressiveness and see in the human hand its independent acting potential. The important thing is to feel one’s hands to be ‘independent,’ in the same way that any puppeteer feels his puppet to be ‘independent.’” This advice, to feel one’s hand to be independent, refers to dissociation, a key moment in puppet training. The hand is separated from the rest of the body: as it no longer can physically manipulate the environment in its conventional way, it loses its “usefulness” and acquires a character, movement and rhythm, all of them autonomous from the rest of the body.

The idea of a synthetic variant for the hand puppet, motivated by Obraztsov’s experience, leads us to consider whether each of the traditional puppetry techniques would contain infinite possible variations and thereby encourages us to sketch a genealogy of the pantomime. Considering the puppet’s capacity to vary, Amparo Ruiz Martorell and Jorge Varela Calvo (1986) present a series of basic modalities, including their derivations, while affirming that “. . . a series of variants have been invented and others will continue to be invented, with their own names or simply as an adaptation to this or that system” (Ruiz Martorell and Varela Calvo 1986, 86). Emphasizing the existence of many types of puppets, and the fact that each one has its own way of performing and its own possibilities of movement, Ruiz Martorell and Varela Calvo try to synthesize general puppetry rules:

. . . our main tool to put a puppet in motion will be our hand and our first task will be to know it . . . we wear it, but we have never used it even in a minimum of its possibilities, both in movement, strength, as in expressiveness. Furthermore, each hand has 5 fingers that can be used together (as is usually done) or independently. (Ruiz Martorell and Varela Calvo 1986, 91-92)

Thus, the reflection on the possible transformations or on the new forms that could emerge from traditional techniques overlaps with the reflections on the human hand and its relationship with the puppet as an object.

In one of her last published books from 1988, Del escenario de teatro al muñeco actor (From the Theatre Stage to the Puppet Actor), Bernardo updates some central notions of puppetry, focusing on certain techniques and emphasizing the importance of knowing them. In this framework, she proposes a classification axis that specifically attends to the relationship between the puppet and the puppeteer, depending on whether the puppet is independent of the latter (marionettes, rod puppets, mixed techniques, and shadows) or integrated into his or her body (hand puppets, marottes, finger puppets, thimble puppets, and pantomime of hands).

The above-mentioned theoretical and scenic reflections about the hand in the puppet theatre draw attention to its paradoxical status and its scenic possibilities, but also reveal a fundamental question that marks the twentieth-century puppet theatre: the tension between traditional and modern forms. This question, to which I will refer later in this article, leaked—intentionally or not—into several reviews of Bernardo and Bianchi’s shows that I will examine next.

All Hands On Deck: Building a Technique

Bernardo and Bianchi’s work with the pantomime of hands for an adult audience can be divided into three phases. The first entailed the presentation of the pantomimes within some particular settings: either a conference with the aim of providing an argument to include this new technique in the world of puppetry; or mixed with other techniques so its presence could go by unnoticed among traditional plotlines and forms. In a second phase, pantomimes became the central spectacle itself, without the need for explanation or justification.[7] Finally, establishing its nature as a technique—pantomime-ballet—a particular form linked to dance, was developed by the artists.

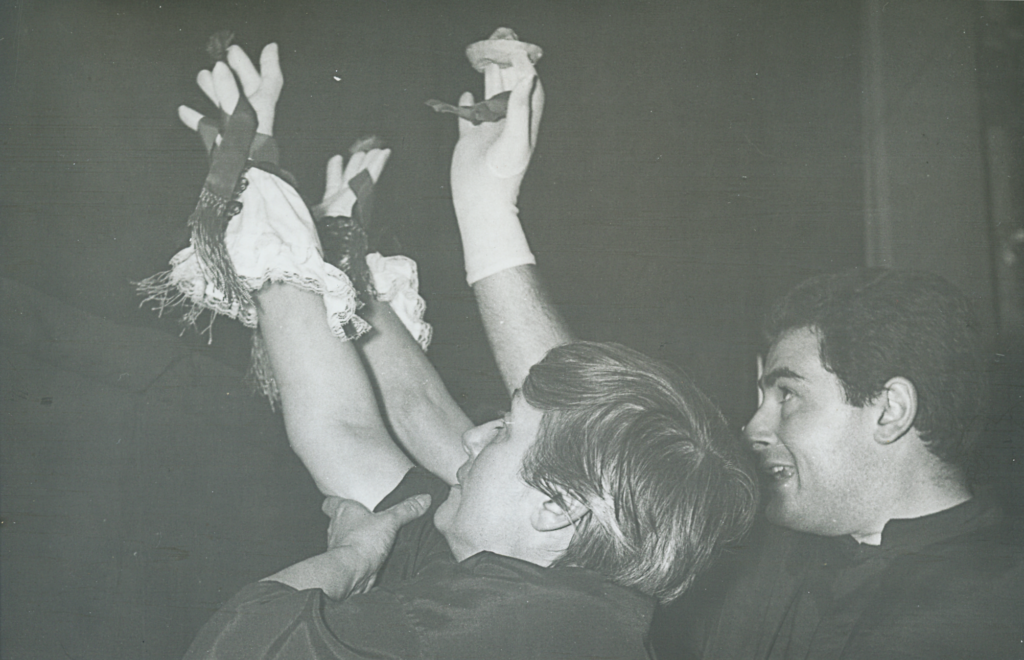

The first version of these shows took place in 1954, as the cast underwent training exercises with the bare hand in order to achieve movement and rhythm dexterity. At that moment—according to the artists—they noticed the expressiveness of the hand without the puppet and immediately decided to test this new form of expression in front of the public (Bernardo and Bianchi 1991).

The technique’s premiere took place at the Teatro Mariano Moreno, where Bernardo and Bianchi organized three adult shows at the end of October. Each show had a different program, in which short acts included in previous shows were combined with the pantomimes Poemas Orientales (Poems from the East) and Ritmos para danza (Rhythms for Dance).[8] In this first version, attention was not placed on the action’s dramatic progression, but on the hands’ movement, which “. . . visually played with rhythms and elements, in performances that were highly celebrated by the public” (Bernardo and Bianchi 1991, 95).

The next step was to give this new technique a storyline. Therefore, Pantomima Elemental (Elemental Pantomime) was created, a play based on the love triangle topos that—according to the artists—staged elemental characters. Although previous questions of dramaturgical structure found resolution in this conventional narrative of conflict, difficulties related to technical issues appeared. Bernardo and Bianchi (1991, 95) recall:

With a lot of fear and expectation we began to develop it by testing the hands for the characters and then looking for appropriate musical themes that fit the different moments. The greatest difficulty was to make a musical montage because the possibility of cutting and splicing as we can do today with tapes did not exist . . . To add to the difficulties, Mane’s voice over the attached microphone introduced the characters and the scene location. We don’t remember which was the first studio we recorded in, but we do remember that it took hours, and that the poor editor perspired because a gunshot had to sound at a certain moment and nothing convinced us; the best test was the piano lid coming down strongly, which sounded like a real gunshot.

This anecdote shows the attention paid to sound and to the technical resources that would define the work with pantomimes and would also allow the incorporation of different technologies in future shows. Instead of working with the live voice, in Pantomima Elemental (Elemental Pantomime) they resorted to narration and recorded special effects; all these recordings were still in use in the late 1980s.

This new act was presented that same year at the Teatro Los Independientes within the framework of a series of conferences organized by the actress Ana Grynn, at which Bernardo also presented an essay entitled “El concepto experimental en el teatro de títeres”(The Experimental Concept in Puppet Theatre). During this presentation, fragments of Pantomima Elemental, performed by the choreographer Alejandro Ginert, Osvaldo Pacheco, and Sarah Bianchi, were shown. For several years after these early experiences, research into pantomime of hands continued behind closed doors.

During the 1960s, Bernardo and Bianchi incorporated different resources and procedures into their research on the bare hand. In 1961, as a continuation of the experience begun in the 1950s, the company decided to test their work “. . . in front of a more restricted and friendly audience” (Bernardo and Bianchi 1991, 141). Thus, in late October that year, Bernardo gave the lecture Dicen y hacen las manos (Hands Say and Do), revealing “. . . the meaning and artistic scope of pantomime” (“En el salón…,” 1961, 12), followed by the presentation of a few examples, in the Assembly Hall of the Sociedad General de Autores (General Authors’ Society).

The audience’s favorable reception led to the organizing of a short season at the Teatro Agón, arranged thanks to a connection between that theatre and one of the cast members, José María Salort. Therefore, for this event the former conference was transformed into an independent show, freeing itself from the lecture framework that justified it and presented in front of the public without the need to camouflage it among other more conventional puppetry techniques.

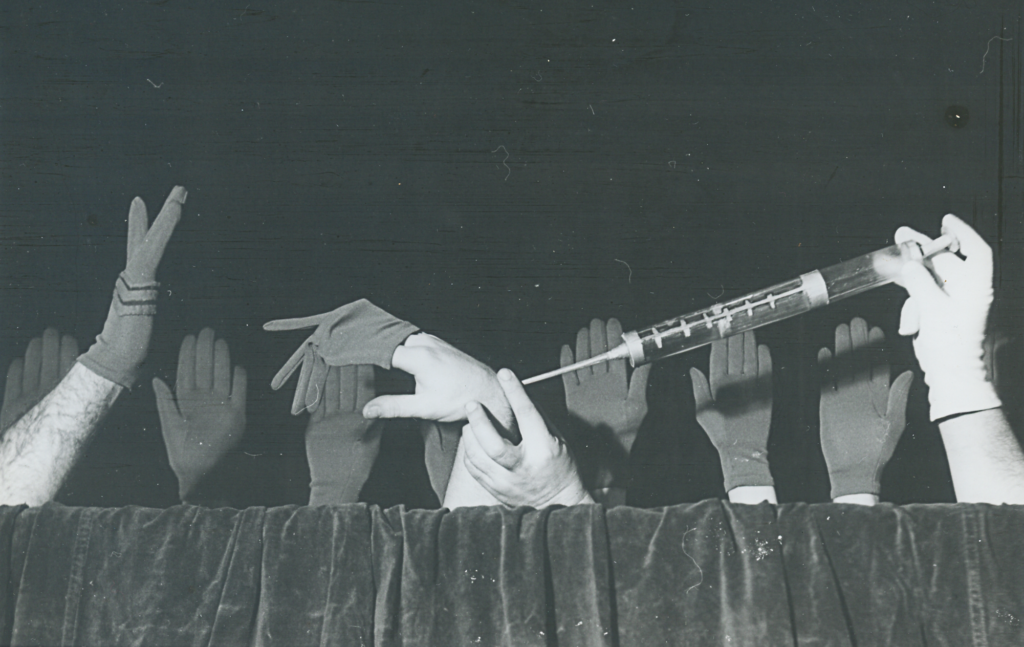

The show at the Teatro Agón kept the conference title. Dicen y hacen las manos was structured as a series of short acts, each one with its own storyline.[9] These, in turn, were each organized into three thematic series: an objective and realistic one, made up of La Bella y la Bestia (Beauty and the Beast), Idilio romántico (Romantic Idyll), Y se casaron (And They Got Married), and Pantomima Elemental (Elemental Pantomime); another series, with a religious theme, was made up of Religiens (a pantomime that incorporated colored lighting and a screen where the hands’ shadows took the form of different objects such as spears, nails or a crown of thorns), El pequeño miedo (The Little Fear), El cerco (The Siege), and El nacimiento de Venus (The Birth of Venus), where the hands appeared naked and were colored with makeup; and, finally, a third series, composed of Desecho (Waste) and Vida de hombre (Life of a Man), in which the hand ceased to be a recognizable character. Perhaps owing to the lecture that served as a frame in the past, in the first two series, the pantomime was here combined with a narration that helped to bring clarity to all acts, designating the characters and locating the action. The third series introduced a new level of abstraction by eliminating the use of words (and, in that sense, eliminating the scene’s explanation), thereby shifting the attention to the movement of the hands.

In a review, the critic Carlos H. Faig highlighted these pantomimic sessions and commented that, although this modality came from outside,[10] here the experience achieved a transcendent meaning. By means of something like a plot summary, Faig (1961, n.p.) explained that

. . . nothing resists the delicious spell of the hands, whether they refer to a legend of bewitchment, or when they show the innocence of a romance of the 1900s, or in the impressive attitudes of the coupling with an electrifying human eloquence, now in the alternatives of the fear or inability to overcome the siege of a persecution, now, in the wonderful vision of sea foam and mythology when Venus is born, without forgetting the dramatic significance that the representation acquires, if you wish to illustrate poems or seek the delivery of things in the prism of changing lights.

Alongside the superficial description of some of the acts of this show and an abundance of adjectives, Faig insists throughout the cited article on the astonishment produced by the pantomimes and their transcendent quality, in opposition to the grotesque nature of the traditional puppet. These aspects of Faig’s review—a vague description of the show, skipping the technique details and emphasizing the idea of “transcendence”—allow us to sense a certain difficulty in apprehending the show and in considering it part of the puppet universe. That difficulty was condensed in the contrast between the grotesque traditional puppet and the transcendent pantomimes, which made concrete the traditional-modern opposition.

Despite the feelings of strangeness that Dicen y hacen las manos could have produced, it was re-staged the following year in the Sala Lugones of the Teatro San Martín.[11] An adaptation of Don Juan (using Hector Berlioz’s Symphonie fantastique) and an act called Exaltación romántica: el duelo (Romantic Exaltation: The Duel) were added to the pantomime program. Along with these, a series of hand pantomime-ballets were incorporated at the end of the show: Silfides (Sylphides), with music by Chopin; Matsuri, with traditional Japanese music; Soleares para el baile (Soleares for dancing), which introduced the Spanish world to music by Emilio Medina; Voodoo, with both ritual and traditional African music; Carnevale napolitano (Neapolitan Carnival); Zamba y malambo (Zamba and malambo), which introduced autochthonous elements of Argentine dance; and Moulin Rouge, set to “Galop Infernal” (also known as “Can Can”) by Jacques Offenbach.[12] These new acts reveal a tendency that we could describe as erudite, both in the selection of their plots and music.

Bernardo and Bianchi’s work process increasingly incorporated more abstract elements. To the series of silent pantomimes released the previous year, they added the pantomime-ballet: acts that used dance to replace mimetic representation. Although the company had dabbled in dance before, thus far those explorations had taken place in the realm of hand puppetry.[13] Thus, the creation of these pantomime-ballets heralded a new phase of bare-hand research.

On this occasion, critics were divided between praise and doubts regarding the artistic results of the experience. For example, one reviewer described the show as an “. . . admirable symbiosis of movement and action . . . ,” highlighting the combination of elements such as “. . . mime, poetry, art, music, anecdote, the poetic touch, the dramatic touch, at times the satirical intention . . .”; emphasizing the use of silence, which “. . . accentuates the suggestion of pantomime . . . ,” and underlining “. . . something very difficult to achieve, and also full of charm: pantomime-ballet” (RGT 1962, n.p.). Another reviewer insisted that the results of this technique were still unknown, based on the fact that the hand

. . . has not yet managed to free itself—and this is the best symptom of the forged process that Bianchi and Bernardo go through—from anticipatory (a poem, a story) or underlining elements (a glove, gauze, a color). The proposition is certainly not simple. It is not easy for the hand, in its helplessness or in its greatness, to reveal or hide feelings, sketch ideas, create images, recreate poetry. Of this inherent difficulty, the program developed by Mane Bernardo and Sarah Bianchi is a sufficient testimony, which in a considerable way constitutes a compromise between new forms, for the independent, and anachronistic, for the conventional. I don’t know if beyond what Bianchi and Bernardo have stated—I don’t think the artists know it yet—the landscape appears fertile, or, if it allows us to hope that in the aesthetic order it will be possible, with the hands and nothing more than the hands, [to] get somewhere. But it is worth finding out. And in this sense the task has an exceptional appeal. (“Las manos…,” 1962, n.p.)

Although the development of pantomimes was moving away from mimetic and figurative conventions, this reviewer emphasized explanatory elements—such as the word, whether in prose or verse, or the objects added to the hands—that were mixed with a new form, the bare hand, separated from the doll.

In June 1963, invited by Jim Henson, the creator of The Muppets and director of the Puppeteers of America at that time, the company presented some of the pantomimes that had premiered previously[14] at the 24th Puppeteers of America Festival, where the English-speaking puppeteers gave the technique the name of hand actors, “. . . a synthesis—in the artists’ words—of what we wanted to be” (Bernardo and Bianchi 1991, 158).

This international experience was followed, in 1964, by a second season at the Teatro San Martín,[15] and immediately followed by another at the Teatro Candilejas. They prepared a three-part program that incorporated new pantomimes and dances. The first one brought together brand-new acts, such as Peleas y Melisenda (Pelléas and Mélisande), Bernardo’s musical adaptation and montage; Barrio de ayer (Yesterday’s Neighborhood); and Mito (Myth), written by Bianchi incorporating black light and with a musical montage of Gustav Mahler’s Symphony No. 1 in D Major, along with the already presented Exaltación Romántica: el duelo. The next part added to the well-known Pequeño miedo (Little Fear) and Pantomima Elemental, were Hasta mañana señorita (See You Tomorrow, Miss); Gaspar o la soledad (Gaspar or Loneliness), written by Alejandro Ginert, in which the foot was incorporated as an actor; and El amor en el tiempo (Love through the Ages), a pantomime composed of five parts: Medieval (Medieval), Renacimiento (Renaissance), Siglos XVIII, XIX y XX (18th, 19th and 20th centuries). The last part featured Idilio 900 (Idyll 900)along with La guerra (War), in which the full use of the hand was tested on screen; Spiritual and four pantomime-ballets entitled Charleston, Ballet africano (African Ballet), Moderno (Modern) and Streaptease (Striptease).

Here again, the artists’ musical knowledge stood out. Likewise, the continuous experimentation in relation to technical possibilities was evident, both in terms of the available technological resources, such as black light or the use of screens, and in terms of the corporal dimension, observed in the incorporation of the foot. If, up to this point the research on the dramatic possibilities of the hand had maintained elements that linked it with the traditional hand puppet, by including the foot, Bernardo and Bianchi took another step out of the realm of the hand puppet. The foot[16], although presented by the artists as a misshapen companion, helped to highlight the corporal quality of the technique.

Critics stressed the show’s originality as well as its attention to composition and the variety of chosen themes:

. . . the singularly expressive language of the hands becomes an element of theatrical interest due to the grace and charm with which its manifestations are transmitted to the spectator, establishing a kind of spiritual communication that is, without a doubt, the best proof that the main goal of the show has been accomplished. That is, to enable the play of the hands to vitalize scenes or motifs with the same reality as if they were made by flesh and blood interpreters . . . “Dicen y hacen las manos” configures an unusual representation, since it is difficult to maintain the attention of an audience with only manual expression, no matter how changeable its themes may be. (“Una representation..,” 1964, n.p.)

This description allows us to suspect that, until that moment, the pantomime of hands (and we could say the puppet, by extension) did not enjoy the status of a theatrical form. This status came together with a comparison that put the work of the bare hands on the same plane as the reality that can be achieved by an actor’s performance.

Bernardo and Bianchi’s work in this line of inquiry continued in the following years, albeit intermittently. In 1966, the comic actor Juan Verdaguer, with whom they had already worked on television, invited them to participate in a show at the Teatro Tabarís entitled ¡Qué noche! (What a Night!), along with Ambar la Fox, Alba Solís, Maurice Jouvet, and Joe Rígoli. Company member Alejandro Ginert created a new choreography for this show. This experience introduced the pantomime of hands into a genre, the teatro de revistas (music hall), hitherto unaccustomed to the world of the puppet, at the same time that it launched the company’s work into a new orbit due to the massiveness of the music hall genre within the Buenos Aires theatre scene.

The following year, Bernardo and Bianchi premiered a new pantomime show in the Teatro Regina, Pantomanos (Pantohands).[17] In this show, they presented new pantomimes: Conscripción (Conscription), a satire; Génesis (Genesis), which combined projections and shadows of hands; La tumba (The Tomb), a play about grave robbers; Op, an op-art ballet; La Macorina, about the Mexican song of that name performed by Chavela Vargas; Vida de Jesús (Life ofJesus); and, as a finale, a variety show that included three Mexican native dances titled Danza del venado (Deer Dance), La Zandunga, and Zapato de Veracruz (Veracruz Shoe), several trapeze artists in black light and a tap dancer, Psicoanálisis (Psychoanalysis), Charleston, Streaptease (Striptease), and a final parade. Months later, a reduced version of this show was performed at Aquelarre, a private venue in which the play lost its exclusivity by sharing space with other activities such as selling art objects.

As part of the company’s 25th-anniversary celebration, in 1971, a photograph exhibition of its shows and puppets was held at the gallery of a former puppeteer, Luis Diego Pedreira. The exhibition was accompanied by a new pantomime of hands, Con las manos en la masa (testimonio escénico) (Red-handed [Stage Testimony]), that combined some of the repertoire acts with three new ones titled Burocracia (Bureaucracy), Estructuras (Structures), and Proselitismo (Proselytism), which delved into the abstract quality of this technique by using a completely bare hand: in other words, without any glove or makeup, and suppressing the spoken word. That same year, the pantomime of hands was used in a new area: advertising. At the request of the owner of the Corcega candy store, the company performed in the shop windows as an advertising strategy. For this show—lasting an hour and a quarter, and offered extensively between 4:00 p.m. and midnight, for several days—Bernardo and Bianchi developed twenty different pantomimes, incorporating elements of the shop windows.[18]

In 1976, a season was scheduled at the Teatro Presidente Alvear, and following the puns used in previous shows, it was entitled ¡Arriba las manos! (Hands up!). On March 24 of that year, the Armed Forces overthrew the constitutional government, marking the beginning of the most brutal civilian-military dictatorship in Argentine history. The de facto government carried out repressive practices using state violence as well as strengthening authoritarian control mechanisms over society, including cultural censorship. The stated objectives were to combat “corruption,” “demagoguery,” and “subversion,” and to place Argentina in the “Western and Christian” world. Although Bernardo and Bianchi acknowledged that the title ¡Arriba las manos! (Hands up!) could be problematic, they explained that they “. . . did not have the chance to change it because a prohibition to present our show had already reached the theatre” (Bernardo and Bianchi 1991, 198). In this context, in September 1976, according to a report from the Secretaría de Inteligencia del Estado (SIDE), Bianchi was accused of being a “subversive,” meaning a dangerous person to the nation. This report not only affected Bianchi’s teaching positions but also had repercussions on their puppet theatre, resulting in a cancellation of the scheduled season. After a year of interrogations and investigations, the ban was lifted and the play was performed in 1977. Finally, in 1981, the last show of the hand pantomimes series premiered at the Teatro Altos de San Telmo. This show, named Hoy: Títeres (Today: Puppets), included shadows, black light, silhouettes, and, obviously, pantomimes of hands.

Experimental and Modern: Towards a Definition of the Pantomime of Hands

Since the mid-1950s, and especially during the following decade, theatre in Buenos Aires would witness innovative projects that modified the relationship between the puppet and the puppeteer. Henryk Jurkowski (2013) observed that a new centrifugal trend had begun to develop in puppet theatre at the end of the 1950s. This trend showed a move away from the traditional puppet and its distinctive features in favor of an enrichment of its means of expression: thus, the human being became a natural supplement to the puppet in the performance.

Although Jurkowski was not referring to Argentina’s theatre when proposing this conceptual change, in those years in Buenos Aires several artists were also exploring the contrast of the human body and the puppet in performances, in line with Bernardo and Bianchi’s pantomimes. For example, poet and puppeteer Juan Enrique Acuña premiered El músico y el león (The Musician and the Lion) in 1964, later defined as an “. . . aesthetic manifesto” (Acuña 2013, 224). The script was inspired by Břetislav Pojar’s animated short film, Lev a písnicka (The Lion and the Song, 1959). In his adaptation, Acuña proposes some innovations; as a result, the work becomes more than a hand puppet play as it adds the presence of an actor and shadow puppets. This artist reflects on the visible participation of human performers in puppet theatre as characters of a different species and of a character of the same species, thanks to the use of a mask. He also observes that the inclusion of human performers as characters in dramatic action, alongside puppets and puppeteers, was more and more frequent, helping to erase, if possible, the difference between “. . . the living actor and the puppet” (Acuña 1965, 16).[19]

At the same time as Bernardo and Bianchi developed their artistic proposal, Bernardo wrote about certain issues related to puppet theatre practice. As stated earlier, on reaching the end of her career, Bernardo proposed a classification of puppets based on the link between puppet and puppeteer and the corporal aspects of that relationship, which included the pantomime of hands. Yet, she did not define this new technique in a single work; her reflections on the bare hand are scattered throughout a series of writings and interviews.

Bernardo’s anecdote of the birth of the pantomime of hands presents it, first, as an accidental discovery and then as an experiment. The latter constituted one of the central elements in her writings. Specifically, in Títere: magia del teatro (Bernardo 1963), considering the creative process as an axis, she goes through the history of puppetry, organizing three eras that overlap and coexist without excluding each other or coming before or after in a chronological way. The first era, which she named the popular era, includes ancient traditions, mainly Eastern forms. The artistic era corresponds to the moment when the artist uses the legacy of the popular tradition to create new forms born of intellectual restlessness. And finally, in the third, the experimental era, the imagination acquires a decisive value, and the puppets intersect with other arts.[20]

Years later, in the aforementioned Del escenario del teatro al muñeco actor, Bernardo recovers and ratifies the organizational scheme of the three eras, adding that

. . . [to] the last of these times belongs the era of the puppet in the twentieth century. Without distancing oneself from the popular era, which is the root, in artistic creation one goes towards experimentation. And that’s why today the most diverse puppetry techniques are applied to curious shows full of expectations, although not all of them are successful. (Bernardo 1988, 16)

In sync with these last statements, the hand without the puppet, either completely naked, dressed with gloves, or wearing makeup (instead of the traditional hand puppet), is presented as a category in a transitional zone located both in the second and third eras, according to Bernardo’s definition. Regarding this view, I would say that the artists collected one of the traditions of Western puppet theatre, the hand puppet technique, and used this legacy to create a new form (artistic era), which, in turn, intersected with other artistic manifestations such as dance and mime (experimental era) and was incorporated into new areas such as advertising.

In an interview about the show Dicen y hacen las manos, Bernardo outlines a genealogy of the pantomime of hands. She places it within an artistic sphere, as it derives from pantomime and from the glove puppet, whose structure was the puppeteer’s hand (in the pantomime of hands, the puppet has been stripped). But she also places it within a religious field, as it was linked to Eastern mudras, ritual gestures (generally made with hands and fingers), typical of Hinduism and Buddhism, and used in the iconography and spiritual practice of these religions. Regarding the creative process, she explains that the theme of each of the acts could “. . . be spontaneously invented or suggested by music, a circumstance or even by the color of a glove” (F.T.P. 1962, 26). This was followed by a sketch of the plot, with special attention to the number of characters, and, in parallel to the stage tests, they began to think about costumes and musical themes. Finally, revisions were made, and in that moment, everything that could be confusing was removed, the movements and positions were specified, and the rhythms were adjusted (F.T.P. 1962).[21]

As we have said, experimenting with dance was not new for this company, which had already prepared ballet numbers and folk dances with hand puppets. Experimenting with mime was different. Considering the absence of words and highlighting the essentiality of the hand movement:

The isolated hand, separated from the human being, is the thing that, in my opinion, gives us the greatest foundation of expression. My whole idea is the transformation of the visual and physical puppet into an expressive essence, abstracting it to a certain point. The hand itself contains only the expression, free from figurativeness: a mixture of the puppet’s and the mime’s expressiveness. The puppet and the mime are both special forms of true theatre, allied in this case to achieve a reflection created within the strictest canons of expression.

The pantomime of hands shows are the ones that, at least for me, have given us the best satisfaction . . . being and not being at the same time fiction and experience. (Bernardo quoted in Bernardo and Bianchi 1991, 218)

With these words, in an informal style, Bernardo suggests that the nudity of the hand, rather than limiting scenic possibilities, enhances them by freeing them from figurative and mimetic obligations, allowing them a greater expressiveness. Likewise, she hints at the essential role of the hand in puppetry, as it is what animates and brings the puppet to life.

That essential role, as we said at the beginning, is marked by the paradoxical status that the human hand acquires in the traditional puppet theatre: it is the hand that, through movement, allows the puppet to be constructed as a dramatic character; however, its presence is denied. The pantomime of hands, by staging the puppet’s movement source—first camouflaged by gloves and makeup, then completely naked or placed in contrast to a bare foot—brings its artificial nature to the fore: rather than hiding the simulacrum—the hand behind the puppet—the pantomime of hands reveals it. In the preface of Títeres y Niños (Puppets and Children) (1962), Bernardo highlights the artificial nature of puppet theatre as one of its constitutive elements, proposing to think

. . . within all the improbabilities accumulated in a puppet show. Nothing is true: the size of the characters (sometimes, especially in hand puppets, you can only see half the body), without trying to hide it; the movements they execute, the immobility of their features and their gaze, which relates them to the masks of Greek theatre or Italian comedy. (Bernardo 1962, 8)

The creation of new forms and their multiplicity, both framed within the second and third eras of Bernardo’s consideration, reappear in Jurkowski’s essay from the late 1970s. Here, from a semiotic approach that recovers the works of Tadeusz Kowzan, Petr Bogatyrev, and Otakar Zich, Jurkowski wonders about the specificity of the puppet theatre, emphasizing what would distinguish it from other performing arts: the link between the puppet and whoever acts as its source of movement and sound. Jurkowski observes this separation in a variety of cases, and this prevents him from asserting that there exists a unity in the link between the puppet and the puppeteer. In addition, he emphasizes that, although this link has been modified over time, it was not the system based on the puppet’s dependence on its sources that has changed, but its parts: in fact, the puppet itself has been modified and this proves that the puppet theatre’s true essence lies in the relationship between the puppet and the puppeteer. He then concludes that

. . . puppet theatre has become a heterogeneous art drawing on many different sign systems. Modern puppet theatre, or at least some forms of it, has become the art of juxtaposing different means of expression (or “signs”), all able to evoke metaphor and so to complicate still further the language of this form of theatre. (Jurkowski 2013, 87-88)

In this approach, the ideas mentioned above regarding the relationship between the puppet and the puppeteer merge with the creation of new forms and techniques. Those new forms and techniques are associated with the transformation of the puppet-puppeteer connection through experimentation with other arts, but also through multiple means of expression and juxtaposition of various techniques, all of this characteristic of a modern puppet theatre.

Final Words

The innovations Mane Bernardo and Sarah Bianchi introduced to Argentine puppet theatre, through what the artists named pantomime of hands, entailed a process of several years of work, at whose center was the adult show Dicen y hacen las manos. Aiming to be presented as a legitimate technique, the first pantomime experiences needed a conference framework to explain and justify them, and to present them alongside other types of performance. The status of an independent show was not achieved until 1961, with the performance at the Teatro Agón and the successive reruns at the Teatro San Martín and Teatro Candilejas, followed up, from 1966 to 1981, by various presentations in different theatres, but also in places beyond the theatrical circuit.

The premiere of Dicen y hacen las manos in 1961 did not mean the end of the explorations around the hand as an expressive medium. The pantomime of hands was perfected in each of the group’s subsequent shows through the incorporation of different elements and procedures: the prominence of the bare hand, with makeup or wearing gloves, without masking its original shape; the incorporation of the foot as a deformed and opposite body; the progressive absence of the word, used at first to present the characters or place the action, and its subsequent replacement with musical elements; a simple dramaturgical conflict, linked to the brevity of the performances; the preponderance of visual aspects through the use of black curtains for the background and for the puppet booth; the incorporation of black light; the pantomime-ballets. This series of technical issues that gave the group formal variety, along with the multiple places where the pantomimes of hands were presented and the enormous diversity of themes and characters explored, account for the ductility and adaptability of the technique.

Regarding the reception of Bernardo and Bianchi’s shows, reviewers agree on the innovation and originality of a proposal that separated the hand from its conventional instrumental function (since the hand suspended its central function in the physical manipulation of the medium), the expressiveness of the executed movements, their ability to captivate the audience, and the bond between this new technique and the traditional puppet theatre, in front of which the pantomime was presented as its derivation.

It is this supposed confrontation with traditional puppet theatre that interests me. Here, I have considered the relationships between the traditional and modern form from the perspective of puppetry techniques. In this sense, traditional and modern should not be treated simply in antagonistic terms, but as two sides of the same coin, presented as opposites, but, at the same time, complementary: the genesis of the pantomimes combined the traditional hand puppet, the basis of this work, with the exploration beyond the limits of the technique itself, in other words, its modernization. Although terms such as reinvention or modernization do not appear explicitly in Bernardo’s theoretical proposals, the organization of three puppetry eras and the importance given to experimentation appear as analogous ideas and pantomime as a modernizing tendency.

[1] This article was originally published in Spanish in Analaes del Instituto de Investigaciones Estéticas Vol. XLV, Issue 122, 2023. Special thanks to Nahuel Tellería (University of Oklahoma) for help with the translation and to the project “Riqueza del Museo Argentino del Títere” for providing and digitizing the pantomime photos.

[2] Bernardo (1913-1991) received her degree as a drawing teacher at the Escuela Nacional de Bellas Artes (National School of Fine Arts), as a professor of engraving at the Escuela de Grabado Ernesto de la Cárcova (Ernesto de la Cárcova School of Engraving), and as a sculpture professor at the Universidad de La Plata. She began working with puppets as soon as she graduated from Fine Arts, invited by the stage designer Ernesto Arancibia (who would later become a film director) to participate in El retablo de Maese Pedro (Master Peter’s Puppet Show) in 1934.

[3] Bianchi began her painting career in the 1940s and had Bernardo herself among her teachers. She mentions that, when she had just completed her teacher training in Literature (in 1942), she began her arts training. The art critic Paul Conquet connected her to Bernardo, who was part of Bianchi’s “[…] list of sacred monsters […]” along with “Raquel Forner, Elba Villafañe, Norah Borges and so many other painters of the time” (Bernardo and Bianchi 1991, 28). Bernardo invited her, first, to join La Cortina, and later, to make puppet heads and paint sets on the Teatro Nacional de Títeres.

[4] The puppeteer’s hands remain offstage in some traditional techniques by having them hang above the puppet stage. Such is the case for string or rod puppets. Or by standing on the sides, for example, in shadow theatre. But they can also be present on stage concealed, as in the hand puppet, a case that we will analyze in the next section.

[5] Throughout this work, I will refer to modern puppet theatre in contrast to traditional puppet theatre. The former is based on the concept of “modernization processes” that is, as part of an historical exercise, observable in all aesthetics during the modern theatre period, and not necessarily linked to avant-gardes or modernisms. Particularly in the case of puppet theatre, this process of modernization has included, among other elements, the combination of different forms and elements and the development of traditional forms with objects alongside new techniques (Bell 2008).

[6] In recent years, several studies have tried to update this classification. Among the many attempts, I turn to Stephen Kaplin (2001), who proposes the actor-puppeteer/object dynamics as a starting point to build a classification system. There are two quantifiable aspects central to his approach: the distance, which applies both to the separation/contact level between object and manipulator and to the separation/contact level between the object and its image, and the ratio, the number of objects in relation to the number of puppeteers. Kaplin arranges these two aspects on perpendicular axes to construct a chart that allows him to highlight the diversity of practices. The intersection of these axes constitutes an absolute contact zone; in other words, there is no displacement between the performer and the performed. As soon as the former begins to represent him or herself on stage, a gap begins to open between the performer and the performed. The displacement is, at first, a simple mental shift, but it will increase as the physical distance between performer and the performed widens.

[7] In the case of children’s shows, Bernardo and Bianchi staged shows that included both hand pantomimes as well as performances using other puppetry techniques.

[8] Wednesday 10/27: La farsa del pastel y de la torta (The Farce of the Pie and the Cake), anonymous French; Federico García Lorca’s El romance del maniquí (de Así que pasen cinco años) (The Romance of the Mannequin [from As Five Years Pass]); Las dos chinelas (The Two Mules), Jorge Horacio Becco adaptation; Danzas Regionales (Regional Dances); Siempre hace falta alguna cosa (Something’s Always Missing), by Carlos Carlino; and La maja majada, a one-act-farce by Ramón de la Cruz.

Thursday 10/28: Coloquio llamado prendas de amor (Colloquium Called Love Garments), by Lope de Rueda; El vendedor de pollos (The Chicken Seller), anonymous Neapolitan farce; Poemas Orientales (Poems from theEast); El dragoncillo, an entremés by Pedro Calderón de la Barca: Estampa norteña (Northern Picture), based on Rafael Jijena Sánchez’s poems; and Primavera traviesa (Cheeky Spring), by Maruja Gil Quesada.

Friday 10/29: Bayle de los elementos ( Dance of the Elements), by Agustín de Salazar y Torres; Famoso entremés de las brujas (Famous Interlude of the Witches), by Agustín Moreto; Ritmos para danza (Rhythms for Dance), coordination by Sarah Bianchi; Ballet Op. 39, by Tchaikovsky; Pedido de mano (A Marriage Proposal), by Anton Chekhov; and Juancito de La Ribera, by Alberto Vacarezza.

[9] In this production, the performers included Beatriz Barbato, Aníbal Cané, Martha Verardi, and Bianca Colonna, the latter also making costumes for the hands; Alejandro Ginert, also served as choreographer; César Fabri and Leónidas Amado, who also collaborated as makeup artists; Osvaldo Pacheco, Andrés Rigot, and José María Salort, who in addition added their voices; Lilian Pellegrini, lighting designer; and María Elena Garmendia, in charge of sound effects.

[10] Although Faig does not specify what he means by “outside,” we believe that it could refer to the work of the Russian puppeteer Sergei Obraztsov, whose works with the bare hand were discussed in the previous section, or to the French puppeteer Yves Joly, who had premiered the show Les mains seules (Hands Alone, 1949) in the late 1940s.

[11] In addition to Alejandro Ginert—who had been participating in these works since 1954—the cast headed by Bernardo and Bianchi was completed with Leónidas Amado, Héctor Blasco, Elvira Buono, Aníbal Cané, Blanca Colonna, and César Fabri.

[12] The choreographies were created by Alejandro Ginert, except for Zamba y Malambo and Moulin Rouge, all choreographed by Mane Bernardo.

[13] In 1948, the company presented a dancing puppet, created by Sarah Bianchi. Below we transcribe Mario Briglia’s description (1951, 10): “[…] this puppet […] transforms and perfects the blackjack puppet, of few and hard movements, allowing it to dance; not the two or three figurative movements, but the most daring twists, contortions, moves and varied positions of extraordinary beauty and plasticity.”

[14] The program consisted of: La Bella y la Bestia (Beauty and the Beast), Y se casaron (And They Got Married), Pequeño Miedo (Little Fear), Idilio Romántico (Romantic Idyll), Pantomima Elemental (Elemental Pantomime), and Ballet, which combined Sílfides (Sylphides), Matsuri, Carnaval Napolitano (Neapolitan Carnival); and Zamba y malambo.

[15] On this occasion, Héctor Blasco and Elvira Buono were replaced by María Elena Garmendia and Lillian Pellegrini.

[16] The foot, also bare, resting on its heel and facing its sole to the audience, upset the other characters, represented by hands. Although we haven’t found explanations of what the creative process was for developing the foot performance, we can imagine there was a focus on highlighting its expressiveness similar to the work done with the hands.

[17] Cast: Leónidas Amado, Mane Bernardo, Sarah Bianchi, AníbalCané, Bianca Colonna, Alejandro Ginert, and Guillermo Molina. Voices: Mane Bernardo, Alejandro Ginert, Aníbal Cané, and Guillermo Molina. Choreographies: Mane Bernardo, Sarah Bianchi, Alejandro Ginert, Leónidas Amado, and Amalia Manzanares. Wardrobe of hands: Blanca Colonna. Makeup: Leónidas Amado and César Fabri. Sound: María Elena Garmendia. Lighting technology: Julio Nuñez. Director: Miros.

[18] The show was created for the candy store’s 35th anniversary, presenting the chocolate as the main theme. For this purpose, they used gloves on their hands as well as chocolate boxes, flowers, and toys. One of the pantomimes depicted Adam and Eve tempted, not by an apple, but by a box of chocolates; another pantomime showed a patient, refusing to take injections, persuaded by the doctor with bonbons.

[19] We must add to the forms of coexistence listed by Acuña the variation developed by Ariel Bufano based on Japanese bunraku, used for the first time with the Grupo de Titiriteros del Teatro Municipal General San Martín in the 1981 play, La Bella y la Bestia (Sormani 1997). A similar tendency to combine actors and puppets can be observed in Brazil, in experimental puppet theatre, especially from the I Festival de Marionetes e Fantoches (First Festival of Marionettes and Puppets) held in Rio de Janeiro in 1966. That same year Ubu Rei (King Ubu) and O Retábulo de Mestre Pedro (Master Peter’s Puppet Show) premiered, both directed by Gianni Ratto, and performed in the actors’ theatre, in which actors, masks, and puppets were combined (Amaral 1994; Beltrame and Silk 2009; Mendonça 2020).

[20] Although the idea of experimentation runs throughout this book, unlike the explanations given with respect to the other two eras—the popular and the artistic ones—, definitions regarding the experimental era are not very precise. It is presumed that these inaccuracies are due to the fact that Bernardo would elaborate on them in El títere y la experiencia (The Puppet and Experience), a work in preparation at that time, but of whose publication there are no records.

[21] In that interview, Bernardo also reflects on the performance work: “[…] apart from having natural conditions of expressiveness in our hands, we must try to make them concentrate all their expressive power only on themselves. More than any other form, hand pantomime requires absolute concentration from the artist, causing in the performer, in the few minutes that each one lasts, a great physical and mental fatigue” (F.T.P. 1962, 26).

References

Acuña, Juan Enrique. 1965. “Títeres y hombres.” Teatro XX [Buenos Aires]. No. 10: 16, July.

______. 2013. Aproximaciones al arte de los títeres. Córdoba: Juancito y María.

Amaral, Ana Maria. 1994. Teatro de Bonecos no Brasil. São Paulo: COM ART.

Bell, John. 2008. American Puppet Modernism: Essays on the Material World in Performance. New York: Palgrave.

Beltrame, Valmor, and Lucrecia Silk. 2009. “A direção de espetáculos no Teatro de Animação no Brasil.” DAPesquisa [Florianópolis]. Vol. 4, No. 6: 1-6. https://www.revistas.udesc.br/index.php/dapesquisa/article/view/14130, accessed February 20, 2021.

Bernardo, Mane. 1962. Títeres y niños. Buenos Aires: Eudeba.

______. 1963. Títere: magia del teatro. Buenos Aires: Ediciones Culturales Argentinas.

______. 1988. Del escenario del teatro al muñeco actor. Buenos Aires: Cuadernos de Divulgación INET.

Bernardo, Mane, and Sarah Bianchi. 1991. Cuatro manos y dos manitas. Buenos Aires: Ed. Tu Llave.

Briglia, Mario. 1951. “El Teatro Libre Argentino de Títeres, Obra de arte de Mane Bernardo y Sara Bianchi.” El Hogar [Buenos Aires]. No. 2152: 10-62,February.

Cappelletto, Chiara. 2011. “The Puppet’s Paradox: An Organic Prosthesis.” In RES: Anthropology and Aesthetics [Cambridge]. No. 59-60: 325-36.

“En el Salón de Actos de Argentores. Dicen y hacen las manos.” 1961. Boletín de Argentores [Buenos Aires].No. 113: 2, October/December.

“F.T.P. El arte en el movimiento expresivo de las manos.” 1962. La Prensa [Buenos Aires,August].

Faig, Carlos. 1961. “Juegos de manos.” Crítica [Buenos Aires, October].

Jurkowski, Henryk. 2013. Aspects of Puppet Theatre. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Kaplin, Stephen. 2001. “A Puppet Tree. A Model for the Field of Puppet Theatre.” In Puppets, Masks and Performing Objects, edited by John Bell, 18-25. New York: MIT Press.

“Las manos como experiencias artísticas.” 1962. Correo de la tarde [Buenos Aires,September].

Mendonça, Tânia Gomes. 2020. Entre os fios da história: uma perspectiva do teatro de bonecos no Brasil e na Argentina (1934-1966). Ph.D. dissertation (Doctorate in Social History), Faculdade de Filosofia, Letras e Ciências Humanas, Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo.

Obraztsov, Sergei. 1950. My Profession. Moscow, Russia: Foreign Languages Publishing House.

“R.G.T. Dicen y hablan las manos. Magia y técnica.” 1962. Clarín [Buenos Aires, September].

Ruiz Martorell, Amparo, and Jorge Varela Calvo. 1986. El actor oculto: máscaras, sombras y títeres. Diputación Provincial de Castellón: Castellón Servicio de Publicaciones.

Sormani, Nora Lía. 1997. “Contribución a la historia del teatro de títeres en la Argentina: la trayectoria de Ariel Bufano.” Letras [Buenos Aires]. No. 35-36: 113-131, January/December.

Trastoy, Beatriz, and Perla Zayas de Lima. 1997. Lenguajes escénicos no verbales en el teatro argentino. Buenos Aires: UBA–FFyL Dpto de Publicaciones del CBC.

“Una representación curiosa con el vivo lenguaje de las manos.” 1964. La Razón [Buenos Aires, August].

Villafañe, Javier. 1944. “El mundo de los títeres.” Cuadernos de Cultura [Buenos Aires]. No. 20: 71-84.