Kathy Foley

The Calling: The Transformative Power of African American Doll and Puppet Making. Camila Bryce Laporte, curator, and Phyllis May-Machunda, curatorial consultant. City Lore Gallery. New York, NY. October 6, 2023 to March 3, 2024.

This exhibit in a one-room space in New York’s East Village seems simple—dolls, soft sculpture figures, assemblage, quilts, and puppets by twenty-six contemporary Black artists juxtaposed in the gallery. Figures are arranged 1) to evoke the chronology of the African American diasporic experience and 2) to create dialogue about loss, trauma, and resilience. Doll making heals the spirit and builds community for these otherwise disparate Black artists active from the 1960s to the present. After discussing what is articulated in the gallery design, catalog (May-Machunda and Bryce-Laporte, eds. 2023, Fig. 1),[1] and online talk (City Lore 2024b), I will discuss some additional differentials of gender, class, and age that inform the exhibit.

The City Lore’s website states that the organization’s mission is to “document, present, and advocate for New York City’s grassroots cultures to ensure their living legacy in stories and histories, places and traditions” (City Lore 2024a). The group achieves its aim with this exhibit of mostly East Coast makers. Curator Camile Bryce-Laporte, a folklife consultant of the Greater Baltimore Cultural Alliance, has successfully expanded ideas and images she articulated in previous displays from 2020-2023 in the Baltimore-Washington area, adding here more Philadelphia and New York area-based artists.[2] The figures each have individual stories to tell, but as a group manifest the trauma yet also self-pride the artists found, as participants stated in the City Lore online talk (2024b), exhibiting together a kind of African American community communal art therapy. In an accompanying catalog edited by Phyllis May-Machunda and Bryce-Laporte (2023), we get biographies, individual artist statements of the presenters, along with introductory essays by the two curators with additional short statements. Bryce-Laporte’s chronological periodization of the African American experience in the US is detailed in her “The Selected African American Doll History Framing The Calling at City Lore Gallery” (pp. 8-13) and the stages she outlines also serve as the exhibit’s spatial design principle: we start with African roots (Figure 1) and end with Black Lives Matter. May-Machunda’s background in using folklore as cultural, group, and individual therapy is clear in her “The Calling:Transformative Power of African American Doll and Puppet Making” (pp. 14-18), explaining her choice of the exhibit title, The Calling.[3] She wants to encompass the ritual-spiritual, historical-rhetorical, and make healing happen. Themes of history and therapy also show in exhibit-related events: On February 10, 2024 Schroeder Cherry’s powerful storytelling toy theatre-esque The Children’s Civil Rights Crusade showed how police arrested busloads of grade school children in 1963 when Black children protested segregation and law enforcement turned local schools into temporary prisons to hold them (Figure 2). Francine Haskin’s art therapy workshop on March 3, 2024 was “Doll Making: A Healing Art for Adults.” [4]

Both Bryce-Laporte and May-Machunda have been associated with The Smithsonian, notably its Center for Folklife and Cultural Heritage, which forefronts concerns for community representation, and with the annual Smithsonian Folklife program developed by Ralph Rinzler, which began in the 1960s. This engagement in public humanities and community empowerment is evident in the City Lore display.[5] Folklore study advanced in American public programming with the 1976 American Folklife Preservation Act as deeper academic study of American folklore was developing in the academy. Indeed, this exhibit’s curatorial pair met in 1978 in a folklore class taught by Steve Zeitlin, a folklorist trained at University of Pennsylvania and the founder of City Lore (p. 6). The pair’s mission in using stories and folk arts to validate and build community, especially for underrepresented groups, is clear. Their calling in mounting this exhibit is to uplift the artists while promoting understanding of Black American culture as a central part of the American experience.

As one enters the gallery, the wall text, with its photos, takes the visitor on a journey from Africa (via the Middle Passage), to the American south, through reconstruction, and on to the present. Early images reference African roots (examples include a Yoruba Egungun masquerade figure by Kimberly Camp and akuaba dolls by Cynthia Sands made in collaboration with Ghanaian carver Awuda (Figure 1). The akuaba (“ba” means child), legend says, originated with the eponymous Asante woman who could not conceive: she began carrying a wooden doll and became pregnant. The flat-faced akuaba images are designed and painted by Sands, who works with both painting and textile arts that celebrate African traditions; her projects are done collaboratively with African crafts persons who reap economic reward from her sales.[6]

An image reflecting on the adaptation of the Africans to early American slave experience is Diana Baird N’Diaye’s quilt “What We Brought from Home: Indigo and Okra, Blood, Sweat, Tears” (2023, Figure 3)—the quilt shows small figures hoeing the fields, the rows represented by strips of indigo fabric. This story cloth communicates the hard labor of slaves and share-croppers in the American south.[7] N’Diaye says in her artist statement: “I am called to tell visual stories about identity and heritage, retold pasts, and aspirational healing [of] both physical and emotional hurts, expressing a positive African American identity through art, and exploring African and African American history” (p. 67).

Dolls associated with early Black American existence include an abayomi doll by Sehar Peerzada and a beautifully crafted portrait doll of the Black Seminole Susan July Horse (Figure 4). Peerzada’s abayomi doll is inspired by figures mothers made for enslaved children. Abayomi means “precious meeting” in Yoruba (p. 73)—lacking sewing materials women tore, twisted, and tied their discarded garments to make playthings for their children. Peerzada uses bright, hand blocked Pakistani fabrics to create her colorful soft sculpture dolls. Among curator Bryce-Laporte’s dolls of strong Black women is the figure of Susan July Horse, a Seminole maroon (Black-Native American mixed race) matriarch who, with her husband John Horse (also known as Juan Caballo, 1812-1882), migrated seeking freedom. They moved from Florida to Indian Territory, on to Texas, and ended up in Nacimiento, Mexico, where John Horse led a troop of Black Seminoles guarding locals against attackers.[8] Bryce-Laporte writes in the catalog of her dolls: “My work is inspired by Black and indigenous women like my own ancestors who are often overlooked or eliminated from the historical text but have made significant contributions to the social and cultural development of the Americas” (p. 33).

Distorted illustrations—the historical Sambo and Golliwog representations and a Black minstrel hand puppet—display the figures of ridicule propagated in the nineteenth and early twentieth century and starkly contrast with the many positive images surrounding them which celebrate Blackness. For example, the stitched figure “In Memory of Urban Fairies” (Figure 5) by Imani Russell uses reclaimed fabric and mixed media—the black face with braids spiking gives the impression of a young Black girl dressed in antique white cotton somewhere in the rural south, regions which the artist visited as a child: “Barefoot on red dirt, blanketed cotton fields, ancestral history, and social issues influence my ideas of Beautiful Blackness” (p. 83).[9]

The back wall brings viewers through the Great Migration to the north up to the 1960s as it combines figures in a representation of the Civil Rights Movement. Dolls from different artists are juxtaposed in front of skyscrapers as if united and on the march. A soft sculpture doll, “Bluebird,” of Washington-based artist Francine Haskins (2022) stands next to Julee Dickerson-Thompson’s “Annie Brown Spices,” Schroeder Cherry’s rod puppet, “Monsieur Cheff” (2020), and James Brown Jr.’s “Omnipotent” (a strong black figure with a white mask on the back of the head, a figure of luck and spirituality, Figure 6). The final wall takes the viewer toward the present and includes dolls as light and ethereal as “Aunt Sadie” (2022) of Paula Whaley (the sister of noted writer James Baldwin, Figure 7) and as down-to-earth as the plastic jug-headed bottle mask with tin-can-top halter dress of Paulette Richards—a figure reminding us that the second life of our trash can save us from ourselves. Gospel is represented too; Laura Gadson’s quilt “For the Sunday Singing Sisters” invites us to the celebration of the Black church.

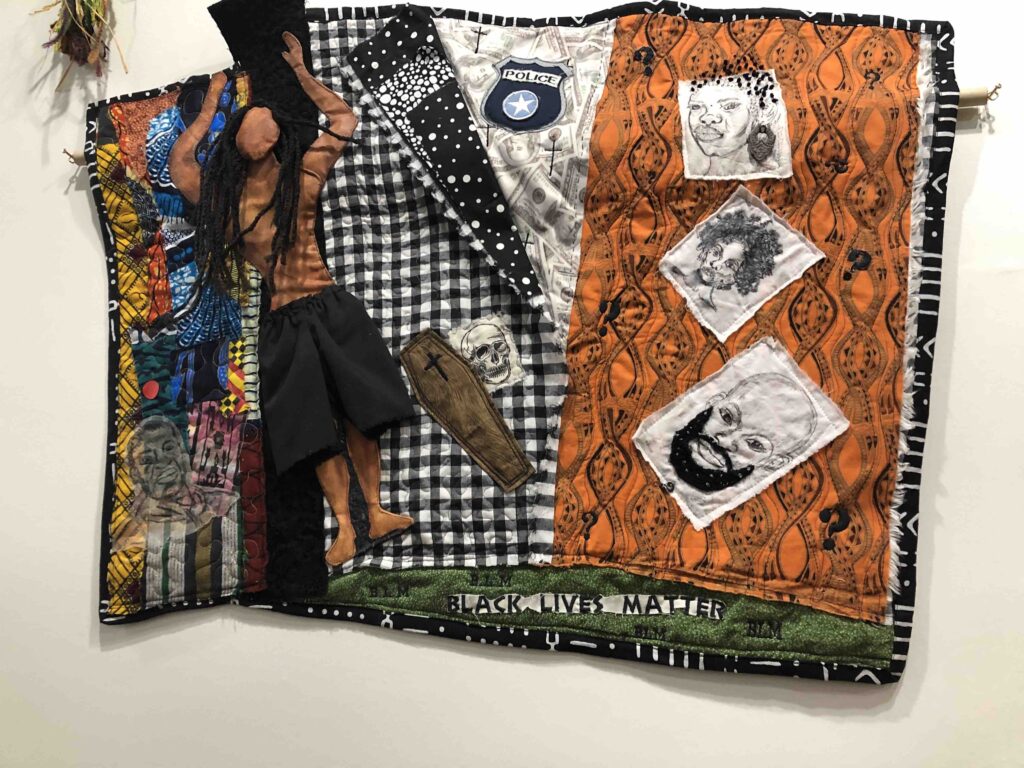

The final pieces on this last wall have Black Lives Matter themes. A 2023 figure by Kibibi Ajanku is an indigo dyed rag doll: glass beads and a cowrie shell form the face (Figure 8); an arm holds a small illustration of a hand raised in a Black Power fist with “Black Lives Matter” emblazoned across its chest. Gloria Gammage Davis’s quilt “Hands Up” (2020, Figure 9) shows a young man with dreadlocks raising his hands in surrender—or is he already laid on the ground in death, given the small coffin and skull lined up by his feet? Bright African fabrics and photos are to the youth’s right, making his image pop out strongly. However, black and white checked fabric claims his left side with this checked cloth peeled back to reveal massed gray twenty dollar bills and a police badge. On the figure’s far left, brown fabric printed with twined vines shows small portraits of victims of police brutality. This “Hands Up” quilt, with the phrase “Black Lives Matter” visible on the bottom, explores the cage and rage of the current situation—so many remain entrapped. Moving down this final wall the viewer comes to the children’s corner and a reception area of the exhibit where a computer station allows visitors to access testimony of individual artists.

Puppets/masks are limited: only Paulette Richards’ plastic jug vision, Schroeder Cherry’s rod puppets, Yolanda Sampson’s Muppet-esque figure used in her gospel ministry are true puppets or masks. The 2019 Ballard Museum exhibition curated by John Bell and Paulette Richards, with its videos, essays, and visual documentation, was more puppet centric (see Ballard Institute and Museum of Puppetry 2020, Bell and Richards 2019). Paulette Richards’ (2024) book on African American object theatre in the United States provides more scholarly depth on the history and recuperation of object performance by current artists and puppet performers. By contrast, this show is doll-centric. For a puppeteer, the figures may seem positioned in the more static tradition of fine arts display—aesthetics of the object are foregrounded. A puppeteer curator might mount figures more in mid-action—the puppet frozen in the interplay of a theatre scene. Here the “movement” the curator seeks is movement of the viewer’s mind toward historical understanding and restorative justice.

Not fully explored though implied are gender, class, and age differentials bound up with dolls. Female artists predominate (twenty-four of the twenty-six). Artists mostly use skills associated with women’s work (they sew, dye, and costume). Both quilts and dresses remind us of women’s tasks, to cover and clothe. “Female” arts (and therefore ones often overlooked) are highlighted rather than wood carving or metal sculpture that are more likely to be executed by males. Class is also involved: skills required for making these figures are mostly “craft” arts, often seen as “low,” because they are used in every-day pragmatic applications of dress and household items. The arts are also “low” because they seem ephemeral: cloth wears out; it fades; it tears. “High” art objects are generally made of relatively permanent materials—oil paints, wood, metal, stone. What is longer lasting is often presumed to be “more important” (“Art”) while the ephemeral is dismissed. Age of the target audience is another issue this exhibit takes on. Despite the tendency of “doll” or “puppet” to make viewers think this will perhaps be a “lightweight” presentation for and/or about child’s play, the topics here are dense. They educate us on history and demand empathy and mature thinking. The first audience of most of the pieces was surely the artist herself. Black women’s thoughts found tangible form through the work of their hands.

The celebration of folk arts and popular culture in public museology was widespread in the 1960s; it emerged at the same time as the civil rights movement and second wave feminism. It was a move toward democratization and emancipation of the exhibit/museum/art world. Equality is what folklore and public humanities invite. But, despite the fifty plus years, the struggle to equalize arts for all is far from realized. The ambition of this show of miniatures is big—it says arts that are female, crafty, soft, and small need our full attention. These dolls are cultural therapy; those who made them, whether female or male, are engaged in deep play. What seems a light and playful practice, doll making, is, as anthropologist Clifford Geertz showed in his interpretation of Balinese cockfight’s “deep play,” important and actually manifests core values of a social group (Geertz 1972).

One exhibit will not bring about the restoration of severed heritages, democratization of the arts, or the other social justice goals these exhibitors seek, but the presentation makes viewers thoughtful. The gallery visit is a “speed though” of time, trauma, and triumphs over adversity. In these mute figures, voices which history, society, and the arts establishment often ignore speak. The Calling sounds its message: those who see it hear.

Kathy Foley

Distinguished Professor and Edward Dickson Emerita Award Professor of Performance, Play, and Design, University of California, Santa Cruz.

[1] Unless otherwise indicated all quotes are taken from May-Machunda and Bryce-Laporte (2023), the exhibition catalog.

[2] For examples of Bryce-Laporte’s previous projects in Washington and Baltimore see YouTube African American Dollmaking and Puppetry: Renegotiating Identity, Restoring Community (2020), the blog by Hall (2021), and the Baltimore exhibit catalog including twelve artists by Bryce-Laporte (2023). These earlier displays had fewer artists represented. For information on other significant recent exhibits regarding Black dolls see Maresca (2015), McGreevy (2022), and New York Historical Society Museum & Library (2022). While The Calling’s catalog details the need for and history of positive representation via dolls in child development, the doll/puppet as toy is not the main subject of the City Lore gallery show. Nonetheless, this important topic is addressed in the catalog and a “children’s corner” did include selected children’s dolls. The gallery provided select child-friendly programming such as Schroeder Cherry’s all-ages performance, The Children’s Civil Rights Crusade.

[3] For more on May-Machunda’s engaged community folklore on different topics, see May-Machunda 2021a and 2021b.

[4] For teaching materials and video documentation of Cherry’s important puppet and storytelling work, see https://www.craftinamerica.org/guide/civil-rights-childrens-crusade and for his portfolio, see https://bakerartist.org/portfolios/schroedercherry.

[5] On City Lore, see the website home and gallery pages (City Lore 2024a, 2024b). For information on Rinzler’s development of the Smithsonian Folklife program, see Gagné (1996).

[6] See Sands’Etuma website at http://www.entuma.com/.

[7] For more on N’Diaye’s work, see her website, including https://ndiayedesign.myportfolio.com/bio and on her quilts, https://ndiayedesign.myportfolio.com/quilt-works.

[8] For oral histories gathered on this Black Seminole group, see Porter (1947).

[9] See https://www.indigosfriends.com/about for more on Russell’s work.

References

African American Dollmaking and Puppetry: Renegotiating Identity, Restoring Community. 2020. Library of Congress, December 3. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZdJOd5XRE3Q [also https://www.loc.gov/item/webcast-9594/?loclr=blogflt], accessed February 17, 2024.

Ballard Institute and Museum of Puppetry. 2020. “2020 Fall Puppet Forum: ‘The Renaissance of African American Object Performance’.” October 23. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fZ1-H0dQBXk, accessed February 17, 2024.

Bell, John and Paulette Richards, eds. 2019. “Living Objects: African American Puppetry Essays,” October 25, 2018-April 7, 2019. https://digitalcommons.lib.uconn.edu/ballinst_catalogues/#:~:text=In%20her%20introduction%20to%20this,in%20relation%20to%20other%20aspects, accessed February 17, 2024.

Bryce-Laporte, Camila. 2023. The Village of African American Doll Artist [Catalog Frederick Douglass-Isaac Myers Museum Feb.-Mar. 2023]. Baltimore: Black Classic Press. https://issuu.com/kibibiajanku/docs/the_village_of_doll_artists_catalog, accessed February 17, 2024.

City Lore, 2024a. [Website]. https://citylore.org. [For information on The Calling Exhibit, see https://citylore.org/about-the-gallery/past/], accessed February 18, 2024.

City Lore 2024b [YouTube]. “The Calling: The Transformative Power of African American Doll and Puppet Making Virtual Program,” [Phyllis May-Machunda, moderator], January 16, 2024. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5WbeRM5B0BgAmerican Culture, accessed February 21, 2024.

“Diana Baird N’Diaye” [Website]. https://ndiayedesign.myportfolio.com/bio [see also https://ndiayedesign.myportfolio.com/work especially “Quilts”], accessed February 21, 2024.

Gagné, Richard. 1996. “Ralph Rinzler, Folklorist: Professional Biography.” Folklore Forum 27, 1: 20-49. https://scholarworks.iu.edu/dspace/items/7ca1743e-cee0-48e0-9444-791190aa4550, accessed February 18, 2024.

Geertz, Clifford. 1972. “Deep Play: Notes on the Balinese Cockfight.” Daedalus 101, no. 1 (1972): 1-37. http://www.jstor.org/stable/20024056.

Hall, Stephanie. 2021. “African American Dolls and Puppets for Identity and Healing.” Library of Congress Blog, February 4. https://blogs.loc.gov/folklife/2021/02/african-american-art-dolls-and-puppets, accessed February 18, 2024.

Indigo Friends [Studio Website of Imani Russell]. 2006-2023. “About the Artist.” https://www.indigosfriends.com/, accessed February 21, 2024

Maresca, Frank, ed. [Text by Margo Jefferson, Faith Ringgold, and Lyle Rexer]. 2015. Black Dolls: Unique African American Dolls, 1850-1930 from the Collection of Deborah Neff. Radius Books/Mingei International Museum [San Diego].

McGreevy, Nora. 2020. “Black Dolls Tell a Story of Play—and Resistance—in America.” https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/african-american-history-black-dolls-toys-180979530/#:~:text=“These%20are%20objects%20that%20were,and%20that%20of%20their%20children, accessed February 21, 2024.

May-Machunda, Phyllis M, and Camila Bryce-Laporte, eds. 2023. The Calling: The Transformative Power of African American Doll and Puppet Making, Exhibition Book. Baltimore: Black Classic Press.

May-Machunda, Phyllis M. 2021a. “Complexifying Identity through Disability: Critical Folkloristic Perspectives on being a Parent and Experiencing Illness and Disability through My Child.” In Theorizing Folklore from the Margins: Critical and Ethical Approaches. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. muse.jhu.edu/book/101398, accessed February 21, 2024.

May-Machunda, Phyllis M. 2021b. “Culturally Conscious Collaborations at the Nexus of Folklore, Education, and Social Justice: Lessons and Questions for Folkloristic Praxis.” In Advancing Folkloristics, ed. Jesse A. Fivecoate, Kristina Downs, and Meredith A. E. Mcgriff, 141-53. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv21hrhkd.14, accessed February 21, 2024.

McGreevy, Nora. 2022. “Black Dolls Tell a Story of Play.” New-York Historical Society Museum & Library, Feb. 25, 2022-June 5, 2022. https://www.nyhistory.org/exhibitions/black-dolls-0, accessed February 21, 2024.

New-York Historical Society. 2022. [Curator Dominique Jean-Louis] “If These Dolls Could Talk: The Hidden History of Black Dolls.” 8 March. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=prNuSUjWa00, accessed February 21, 2024.

Porter, Kenneth Wiggins. “Farewell to John Horse: An Episode of Seminole Negro Folk History.” Phylon (1940-1956) 8, no. 3 (1947): 265-73. https://doi.org/10.2307/272343, accessed February 21, 2024.

Richards, Paulette. 2024. Object Performance in the Black Atlantic: The United States. NY: Routledge.

Sands, Cynthia. n.d. Etuma. http://www.entuma.com/, accessed February 19, 2024.

“Schroeder Cherry’s Art Portfolio.” Baker’s Art Portfolios. https://bakerartist.org/portfolios/schroedercherry, accessed February 19, 2024. Crafts In America.

Shroeder, Cherry. “Civil Rights Children’s Crusade.” PBS.org. [For Cherry’s work, see https://www.craftinamerica.org/guide/civil-rights-childrens-crusade, for his portfolio, see https://bakerartist.org/portfolios/schroedercherry], accessed February 19, 2024.