Portrait of the Puppeteer as Author: Second International PuppetPlays Conference: Writing Practices for Puppets in Western Europe (Seventeenth – Twenty-first Century). Université Paul-Valéry Montpellier 3, Montpellier, France, 23-25 May 2023.

This report provides an overview of the second PuppetPlays project conference that explores authorship and what constitutes a play script in a broad range of historical and contemporary puppetry. The review includes a link to the conference page that has videos of all conference sessions in French, Italian and English as well as links to artist pages.

Alissa Mello, PhD, is Marie Skłodowska-Curie Postdoctoral Research Fellow at University of Exeter (2022-2025). She was a Fulbright Fellow on Listaháskóli Íslands in 2018. She is co-editor of Women and Puppetry: Critical and Historical Investigations. Her current book projects include co-editing Race, Gender and Disability in Puppetry and Material Performance with Paulette Richards and Laura Purcell-Gate, under contract with Routledge, and co-editing Making Meaning with Puppets: Material, Performance, Perception with Dassia Posner and Claudia Orenstein, under contract with Routledge. She is Editor of the UNIMA-USA magazine Puppetry International.

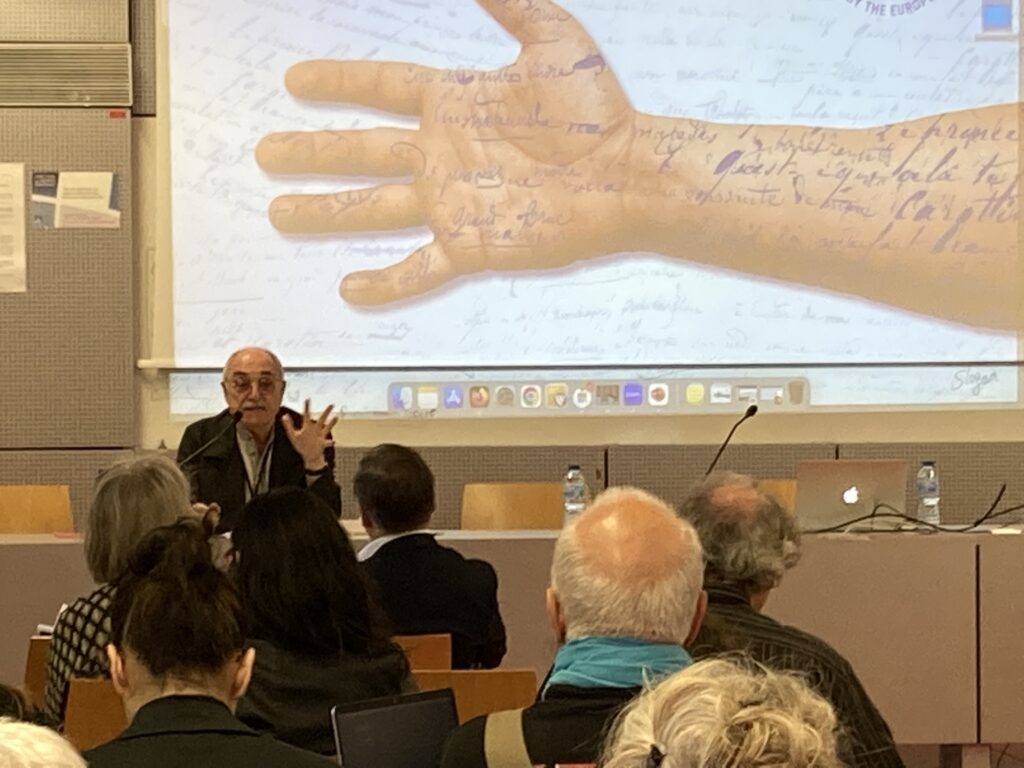

To quote the title of a 2021 anime, “words bubble up like soda pop,” an adept description of the feeling that continues to linger although it has been weeks since I attended the second conference presented by the PuppetPlays project Portrait of the Puppeteer as Author. The conference was presented at the University Paul-Valéry in Montpellier and is funded by a European Research Council Horizon 2020 grant. It brought together artists, scholars, curators, and other theatre professionals to think about authorship in puppetry and material performance and included twenty-three sessions with forty-nine speakers presenting in French, English, and Italian with simultaneous translation, two performances, and many ad hoc conversations during breaks, lunches, and dinners. The presentations and conversations offered a deep dive highlighting the complexities not only of scripting movement-based visual theatre but also of the challenges of researching, documenting/tracing oral traditions, puppetry in general, and excavating the work of often marginalized practitioners whose work has left little or no trace in institutional archives. Like many a good conversation, the conference raised more questions than it answered.

In this current puppet moment, which arguably has been in process since the late 1950s, puppetry seems to be experiencing a far-reaching presence on experimental and commercial stages as well as big and small screens as a re-invigorated site to interrogate cultural, social, and political landscapes. As a performance form with a long history in local and global contexts, it is transnational, transcultural, interdisciplinary, and intersectional. Within this complexity, ideas about authorship and scripting were joyfully and intensively investigated alongside notions of “play” as both a process that is continually evolving in response to contexts as well as it being a language-based product. In its most traditional form, it is a play script, which now may also include recordings (audio and video), documenting a specific instance of performance at a particular time for a specific audience.

A few core questions that reverberated throughout the presentations were: Who authors a play script? How might plays with minimal or no text be documented? How do we document oral traditions? What is lost and what is gained in the process of documentation? Who can claim ownership of a play that may begin life with a writer but that also evolves with each new cast, puppet, director, scenographer, composer, et cetera? How do diverse actors inform and shift a playscript? How might we document or account for adaptations from well-established texts? How might we imagine new ways or means of documentation that allow for movement-based, visual “plays” to be notated and interpreted across cultures, time, place, objects, and people?

Many presentations on the first day, all of which will be available for viewing on the project website, focused on traditional forms, mostly French Guignol and Italian Sicilian marionettes with some reference to the English tradition of Punch and Judy. I was excited about this start of the conference because of the ways the challenges and questions about authorship, archives, and what constitutes a text in often oral popular forms intersect with my current research on the Punch and Judy tradition. The conference opened with Paul Fournel’s keynote. This noted French writer, poet, publisher, cultural ambassador, and regent of the College of Pataphysics set the stage, interrogating oral traditions that are grounded in memory and un-written texts that are calibrated to specific audiences in real time at the moment of performance. Though unwritten, language and geography of any given repertoire, meaning that which is created by and for a localized audience at a specific time and place, was the thread that also connected presentations by Giuseppe Polimeni and Valentina Petrini of the State University of Milan, and Alessandro Napoli, a puppeteer from Catania, Italy. This thread was then extended by those presenters who followed who investigated puppetry interpretations of plays (see presentations by: Alfonso Cipolla, president of UNIMA-Italy; Francesca Cecconi, University of Verona; and Yanna Kor, University Paul-Valéry Montpellier 3) or families who meticulously created and handed down their working scripts (see presentations by: Anna Leone, University of Montpellier 3, on the important Italian Ferraiolo family active from the 1850s; and Jo-Ann Cavallo, Columbia University, on the Sardini family in northern Italy presenting the Palidins of France from 1880 to 1958). In different ways these presentations highlighted the limits of institutional archives, their holdings, and how a “playscript”, as it is commonly defined, often elides oral traditions. Puppetry master, Bruno Leone of Casa delle Guarattelle, Naples, often credited with saving the Neapolitan Pulcinella puppet tradition from extinction, further challenged ideas of performance texts and authorship when he said (and I am paraphrasing) that from his point of view there is a finite number of words but infinite and diverse configurations of objects, puppeteers, their states of being, audiences, locations, classes, genders, et cetera, all of which come together to make and shape plays and performances by their very material existence. Leone put this into action on day two of the conference with his performance Pulchi Shake & Speare, a mashup of Italian hand puppetry and much of Shakespeare’s repertoire in about forty-five minutes. Mervyn Millar, whose work with object theatre includes working on the productions of War Horse for the National Theatre in London (2007) and My Neighbour Totoro for the Royal Shakespeare Company (2022), closed the day, foreshadowing what would be a shift to discussions of more contemporary works, with a provocative artist’s talk about the negotiations among a text-based script, actors, sound, design, and puppets as these played out in these two international mainstage hits; the day ended with a screening of the 2014 National Theatre, London, film version of the play War Horse.

Day two brought the twentieth and twenty-first centuries more into focus. It began with Didier Plassard, the lead investigator on the PuppetPlays project and professor at University Paul-Valéry Montpellier 3, who set the stage for the day by inviting those present to reconsider how we keep the memory of shows when there is little left about an event as it happened, questioning the tensions between a performed event and its crystallization as a written text that is separate from and representative of a performance, and how these sometimes two very different texts of a single event each constitute a type of script. Artist talks such as those by Frank Soehnle of Germany (Figurentheater Tübingen https://www.figurentheater-tuebingen.de/en/), Mexican-born and Valladolid, Spain-based artist Shaday Larios (Microscopía Teatro, http://microscopiateatro.blogspot.com/), British practitioner Tim Spooner (https://timspooner.com/), and Stuttgart-based Iris Meinhardt and Michael Krauss (https://www.meinhardt-krauss.com/seite/559037/about-us.html) offered a taste of the breadth of contemporary work that engages with very different types of performing objects such as string marionettes, everyday personal objects, and robotics. Although the conversations spanned a wide gamut, each spoke to the power of puppets, objects, and things as actants that craft texts and de-center the human experience while simultaneously expressing depths of social experience and emotion. Equally engaging were presentations by: Carole Guidicelli (Université Paul-Valéry Montpellier 3) with her analysis of Compagnie Philippe Genty and their “writing” methods for non-verbal performances; Barcelona puppeteer Toni Rumbau’s discussion of the function of puppets as a way of seeing ourselves; and Cécile Bassuel- Lobera’s (Lycée Joffre, Montpellier) investigation of fluid text in the work of the group Bambalina Teatre Practicable (https://bambalina.es/en/) from Valencia, Spain, that has a multi-sensory approach to the creation of performance texts that incorporates silence, sound, and dialogue alongside of visual and tactile experiences of puppetry.

The intensity of the previous two days continued into day three, beginning with the third keynote presented by the Strasbourg, France based artist Renaud Herbin (L’étendue, http://www.renaudherbin.com/open-the-owl/). Herbin focused on their development process and how being guided by material and going with its flow can lead to unimaginable dramaturgical surprises. This focus on artistic process continued with University of Lisbon researcher Catarina Firmo’s presentation about the work of Lisbon’s puppet company A Tarumba (https://tarumba.pt/2023/pt/tarumba) and a round table featuring four leading European shadow puppeteers—Germany’s Norbert Götz (Theater der Schatten [Theatre of Shadows], https://www.theater-der-schatten.de/en/theatre/), and three French artists Michèle Augustin (Cie Amoros et Augustin, https://wepa.unima.org/en/amoros-et-augustin/), Jean-Pierre Lescot (https://wepa.unima.org/en/jean-pierre-lescot/) and Aurélie Morin (https://letheatredenuit.org/). The investigation of “texts” was further explored by Hana Ribi in the context of anti-war puppet cabaret in Switzerland. The Munich City Museum’s Mascha Erbelding gave an analysis of Hamlet on German puppet stages, while co-founder and puppeteer-director of British theatre company Rogue28, Paul Piris, dissected co-presence in the work of the Belgian Compagnie Mossoux-Bonté.

PuppetPlays is a five-year European Research Council project about puppet repertoires in Western Europe. To learn more about the project visit https://puppetplays.www.univ-montp3.fr/en. Although there are no further conferences planned, all sessions have been recorded, most with translations in English, which are noted when you go to a session page. To download the conference program for Portrait of the Puppeteer as Author visit https://puppetplays.www.univ-montp3.fr/en/conference-portrait-puppeteer-playwright. To access recordings of all project events including this conference and their first conference, Literary Writing for Puppets and Marionettes, visit https://puppetplays.www.univ-montp3.fr/en/actions-0. To learn more about the open-source database of published and unpublished plays that is currently in development visit https://puppetplays.www.univ-montp3.fr/en/platform. These myriad resources are a gift to those pondering the questions posed by the many presenters currently working to better historicize and document our visual, contextual, and ever evolving art.

Alissa Mello

Marie Skłodowska-Curie Postdoctoral Research Fellow, University of Exeter