Theatrical representations of history have a profound influence on the emotional connection of audiences to the past while shaping their perception of events. This paper delves into the aesthetic choices employed in portraying traumatic history, focusing on the utilization of what I am calling “the puppetry doubling technique,” which creates a distinctive reflective aesthetic, distinguishing past experiences from the way they are remembered. By presenting protagonists as both puppets and puppeteers, these performances create a space for reflection, enabling the audience to engage with the past in a meaningful way that often transcends the impact of vivid documentary enactments. I exemplify this aesthetic approach through two one-woman puppetry performances based on the biographical stories of Holocaust survivors who, as young girls, hid their identities in their attempts to escape Nazi persecution.

Achinoam Aldouby is a PhD candidate in the Department of Theatre Arts at Tel Aviv University and a Visiting Scholar at The Helen Diller Institute for Jewish Law and Israel Studies, UC Berkeley. Her research focuses on the theatrical adaptation of canonical texts, rituals, and historical events as a means of exploring aspects of collective memory and identity formation. Her current PhD project is entitled: Theatrical Representations of Shoah Memory in the Early 21st Century Israel.[1]

Theatre has long been an important arena for confronting past events (Favorini 2008 and Rokem 2002). The aesthetic choices made by artists in portraying history have a powerful influence on how audiences perceive and remember events. When audiences have an immediate personal or cultural connection to painful histories that are portrayed, aesthetic choices can play a crucial role in shaping the audience’s emotional experience: they can either evoke strong feelings of trauma or aid in the process of understanding and reconciliation with the traumas of the past. Therefore, it is important to carefully consider the aesthetic in which past events are represented.

This paper discusses the potential of puppetry to present traumatic historical events by employing a reflective aesthetic, distinguishing past experiences from the way they are remembered. This approach creates a space for contemplation, enabling the audience to engage with the past in a critical way, rather than reliving it through iconic enactments. I present the techniques used to achieve the reflective aesthetic by analyzing two one-woman contemporary Israeli puppetry performances: Ian’s Daughter (Bito Shel Yan) by Patricia O’Donovan (2003) and Otherwise (Ilmale) by Elit Veber (2014).[2] Both performances delve into the arduous memories of Holocaust survivors who, as young girls, concealed their identities in their attempts to escape Nazi persecution. Through the use of what I am calling here “the puppetry doubling technique,” these performances use puppetry to double the characters of the survivors, casting them as both puppet and puppeteer. The puppet is the child experiencing the past, while the puppeteer is the adult, reflecting on those childhood experiences in the present, decades after the traumatic events that they experienced. This technique facilitates the expression of fractured identities and shattered narratives caused by trauma, while simultaneously promoting reflection and potential reconciliation with traumas of the past.

This paper contains three parts. The first part discusses the reflective aesthetics of staging the Holocaust, focusing on the significance of puppetry in dealing with the traumatic experiences of child survivors. The second part analyzes the performances, focusing on the “doubling” technique that enables reflection. The third part delves into the significance of puppetry as a medium that can provide the audience an arena to gain a nuanced understanding and confront a painful past.

Introduction: The Aesthetics of Holocaust Representation

The brutal systematic genocide during the Holocaust has become central to Western historical consciousness as a symbol of ultimate human evil. Between 1941 and 1945, Nazi Germany and their collaborators systematically murdered millions of Jews across German-occupied territories. The Holocaust is a recurring topic in theatrical performances worldwide, particularly in Israel (Feingold 2012). A significant body of research analyzes the impact, ethics, and changes in the aesthetics of the portrayal of the Holocaust. (See Guedj and Shiff [2022], Plunka [2009], Schumacher [1998], and Skloot [1988].)

Twentieth Century: Documentary and Aesthetics of Fragmentation

Research on the theatrical representation of the Holocaust examines how evolving aesthetics reflect the ability to address both individual and collective trauma. From the 1950s to the 1980s, the aesthetics of allegory (presenting something through something else) and documentary (representing primarily sources that shed light on a part of the event) were often implemented in dramatic presentations of the Holocaust (Barzel 1995, 269-300). Although both are valuable aesthetics, they are not capable of fully expressing the traumatic experience, as allegory cancels out the connection to a specific time and space, while documentary is bound to historical facts without leaving room for expressing fragmented experiences. In the 1980s and 1990s, artistic representations of traumatic events shifted towards a postmodern style intentionally avoiding arranging memories in a factual linear or coherent manner (Malkin 1999). This aesthetic exaggerated traumatic experiences through deconstructive methods like non-rational images, long static monologues, contradictory information, and overlapping sounds. This aesthetic of fragmentation expresses the past without order, emphasizing physical experience rather than a complete story. The postmodern aesthetic of fragmentation was also incapable of effectively presenting memory, as it paradoxically breaks apart the very memories it aims to represent. (For additional discussions see Favorini [2008], Kaynar [1998], and Martin [2012].)

In the twenty-first century, as a response to evolving artistic landscapes and cultural sensitivities, a new aesthetic trend is emerging within Israeli theatre. This trend introduces a fresh approach to presenting Holocaust-related events that is distinct from earlier methods of depicting trauma through what I call a reflective aesthetic.

Twenty-first Century: The Reflective Aesthetic

Unlike the documentary and the aesthetics of fragmentation approaches that evolved in the twentieth century, in the early twenty-first century Israeli theatre there are a growing number of performances that offer a reflective perspective on memory. This reflective aesthetic emphasizes the distinction between the experience and the memory of the experience, highlighting the divergence between the past and how the past is remembered.[3] Reflection is a process of looking back at an event or action that has taken place. The term “reflection” comes from the Latin word reflectere, which means “to turn back.” According to John Dewey, reflective thinking is often connected to a state of doubt, confusion, or mental difficulty that prompts individuals to rethink their experiences and to critically evaluate them (Chittooran 2015: 79). The goal of reflection is to challenge basic assumptions and create a deeper and more complex understanding of the way we perceive.[4] My research on theatrical representations of the Holocaust in early twenty-first century Israel examines various theatrical techniques used to achieve the reflective approach, with one effective method being puppetry.[5]

Puppetry and Child Survivors

In the past century, puppetry in Western theatre has shifted focus from magical animation of lifeless objects to expressions of sophisticated relationships between the puppet and the puppeteer. In these often complex relationships, the puppeteer is the puppet’s “God,” life-giver, and simultaneously the puppet’s servant, providing all of their needs. Although the puppet depends on the puppeteer, the puppeteer also depends on the puppet to express him/herself. The puppet, as ego-less material, offers options to express things that the puppeteer cannot express with their own words, voice, and gestures.[6] Puppetry’s development, featuring both puppeteer and puppet on stage, allows for the doubling technique to portray complex relationships, including one’s connection with their own past self. In the case of representing child survivors, this becomes particularly significant, considering the intricate and challenging experiences they have endured.

The Doubling Technique

In this paper I discuss the puppetry doubling technique which involves portraying a character as both a puppet, experiencing the story in the past, and a puppeteer, reflecting on past experiences in the present. This technique combines postmodern aesthetics of fragmentation that convey shattered past experiences, expressed through the puppet, with factual-documentary aesthetics, provided by the narrator’s puppeteer, who creates context and offers a coherent narrative.

The significance of the doubling technique in presenting traumatic past events can be understood through the Two Selves theory proposed by Daniel Kahneman and Jason Riis (2005). The theory differentiates between actual experiences and memories of them by proposing that the human mind consists of two selves. The Experiencing Self knows only the emotional state of subjective feelings in the present moment. The Remembering Self, a storyteller of the memory of the experienced moment, interprets the past to influence current actions and future decisions (Kahneman and Riis 2005).

Charles Rycroft (2015) also differentiates between the Past “me” and the Present “I.” The Past “me” experiences the past while the Present “I” reexamines those past experiences. The dialectic between the Present “I” and Past “me” has the capacity to influence the processing of the event. After processing, the author-subject could say both “I wrote it” and “It wrote me” (Pendzik, Johnson, and Emunah 2016, 192-193).[7] Puppetry doubling techniques enable this dialectic between the Two Selves by simultaneously presenting introspection and retrospection of traumatic experiences. The puppet child embodies the Experiencing Self (Past “me”), while the puppeteer adult embodies the Remembering Self (Present “I”). While the puppet child expresses the fractured, fragmented parts of shattered identity, the puppeteer adult ties those fractured moments into a coherent narrative, by both interpreting and providing significant meaning.

The puppet-theatre performances discussed in this paper add another layer of complexity to the already multifaceted dynamic between puppets and puppeteers, particularly when they portray stories of little girls. In the Latin linguistic context, the word puppet or poupée evolved from the term pupa—translated as a little girl or a doll. In Hebrew, the word for both puppet and doll is bubah, which is a feminine noun.[8] Therefore, staging stories of little girls with puppets is connected in these linguistic roots (Gross 2019, 11). In cultural contexts both puppet and bubah often refer to a woman or a child in the realm of social and sexual subordination.[9] At the same time, puppet and bubah also describe transformative growth processes that are gateways to new understanding.[10] Presenting stories of little girls as puppets can serve to express helplessness while highlighting a character’s potential transformation in recreating themselves. Puppetry therefore can be both a powerful expression of suppression and of transformation. This duality is a central theme in both theatrical pieces that use a double representation of the protagonists—child survivors of the Holocaust.

Child-Survivors of the Holocaust

Approximately one and a half million children were murdered in the Holocaust. Some of the children who survived hid with Christian families where they carefully concealed their identities, including their names, origins, and ethnicity. Research emphasizes the contrasts between adult Holocaust survivors, who remember a pre-Holocaust reality, and children who grew up during the Holocaust without basic structure and stability, often with blurred memories of their birthplaces, families, and even their mother tongue. The need to conceal their origin, true name, and ethnicity during their critical formative years significantly impacted the physical, cognitive, and social growth of child survivors, affecting their ability to solidify their identity. Child survivors who experienced the challenge of compromising their shattered identity are a unique subgroup among survivors (Plunka 2018, 74-100).

Experiences of children in the Holocaust are present in diaries, films, and many books.[11] The experience of children in hiding began being portrayed as stage adaptations within a decade after the Holocaust, including the productions of Frances Goodrich and Albert Hackett’s The Diary of Anne Frank (New York, 1955) and Leah Goldberg’s The Palace Owner (Baalat HaArmom)(Tel-Aviv, 1955). (For additional discussions on these plays see Aldouby and Goldfarb-Zarchin [2020], Guedj and Shiff [2022], and Feingold [2012].) While the portrayal of children in hiding was relatively early in post-war stage productions, Gene Plunka emphasizes the limited number of scripted plays that specifically delve into the long-term traumatic effects endured by these children. This scarcity of theatrical works stands in contrast to the broader exploration of trauma in other survivor narratives (Plunka 2018, 78). This paper aims to broaden the scope of research by analyzing puppetry performances that depict the stories of girls who went into hiding, exploring both their past experiences and their adult confrontation with childhood memories.[12]

The portrayal of both the experiences and the memories of child survivors in these performances elicit various themes, for example, the staging of atrocities and child-parent or predator-victim relationships. This paper focuses on the relationship of survivors with themselves, concentrating on their identities, through theatrical conventions that distinguish between the Two Selves (puppets-child and puppeteer-adult). While the materiality of the puppets and theatrical elements are central to the discussion of puppetry preferences, this paper will focus on puppets’ function in the theme of identity.

Ian’s Daughter: Proximity and Distance

Ian’s Daughter tells the childhood story of Hannah Yakin (born on 3 March 1933, to the Van Hulst family in Amstelveen, Netherlands).[13] On 10 May 1940, when she was seven years old, her life and the lives of her family and the local Jewish community were threatened as the Nazis occupied the Netherlands. The Nazis implemented racist policies based on the belief in Aryan race superiority, leading to the extermination of those they deemed “sub-humans,” with a special focus on the Jewish people. Hannah’s father, Ian, a Christian, joined the underground rebellion by disguising himself as a dedicated employee of the Schutzstaffel (SS), a major paramilitary organization responsible for the genocidal murder during the Holocaust. Ian’s connections helped him to succeed in changing the birth records of Hannah’s mother, enabling his family to live while hiding their Jewish identity by overtly practicing Christianity, and assisting other Jews to go into hiding. The Nazis eventually began to suspect Ian, forcing his wife and family to flee for their lives.[14] In 1956, Hannah emigrated to Israel, where she developed her career as an artist and recorded her childhood memories in a book entitled On Tortoise and Other Jews (Al Tzabim VeYehudim Acherim) (Yakin 2015).

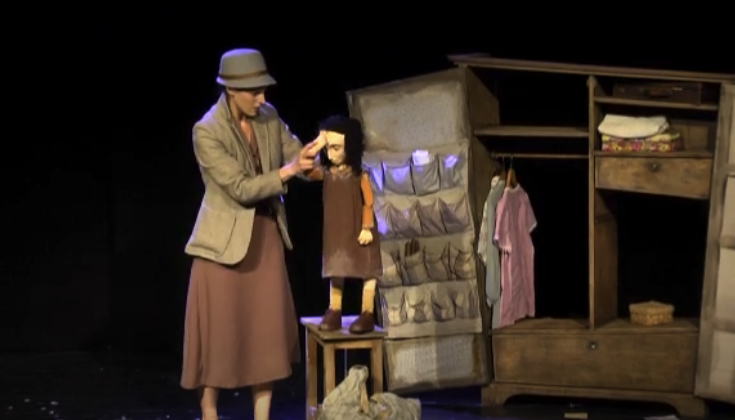

Hannah’s close friend, Patricia O’Donovan, who creates visual theatre that combines puppets and objects, read Hannah’s autobiography and was intrigued to adapt the story for the stage.[15] O’Donovan spent two years looking for an effective way to convey on stage the complex experiences of a child in a war that includes portraying horrors and expressing questions of race and identity. She specifically aimed to find a suitable aesthetic choice to portray the trauma of child survivors to a children’s audience that can empathize with the child.[16] Eventually, she settled on the puppet doubling technique as a way to reflect on the memory she is presenting. She titled this piece Ian’s Daughter.[17]

Puppets and Puppeteer: A Perspective on Time, Place, and Experience

In Ian’s Daughter, the doubling technique involves three portrayals of Hannah, who is referred to by a different name — “Anita”:[18]

- Anita the Adult – The protagonist puppeteer actress who embodies Hannah as an adult Remembering Self, reflecting on her childhood memories.

The reflection of the past events is depicted through two portrayals of the child Experiencing Self:

2. Anita the Child – embodied by the puppeteer actress, and

3. Anita the Child Puppet – a puppet representing Anita as a child.

The performance opens with a prologue, a poetic scene that creates a perspective on the act of remembrance. O’Donovan enters the scene and looks down upon a quaint, miniature village made of wooden blocks. She holds an angel puppet—alluding to Walter Benjamin’s Angel of History—an angel who looks backward on the past but flies toward the future without the ability to change what will transpire (Benjamin 2003, 392). The angel hovers over the village, picks up a house, and rocks it in a movement that can be interpreted as either trapping or protecting.

After the prologue, O’Donovan introduces herself, explaining that she will share the true story of a woman named Hannah Yakin. She stands near the miniature village, observing it for a long moment. Then, without changing anything in her appearance or voice, she becomes Anita the Adult presenting the village of her childhood:[19]

This is the village Amstelveen—near Amsterdam, in the Netherlands—where I was born. From up here—all the houses look the same, with the red roofs and backyards… and the bike paths… (She then kneels and picks up one of the wooden blocks.) Here is Lotte’s house—she used to be my best friend in school. (Picking up another block) This is my house…. (O’Donovan 2003: 2:10-2:30)

After presenting the village, Anita the Adult spreads a blanket on the stage floor, depicting the blueprint of her childhood home. After observing the blueprint for a long moment, she sits on a blanket cross-legged. By making herself “shorter” and her voice just a little softer and without changing anything else in her appearance, she transforms into the character of herself as Anita the Child. She then picks up a wooden puppet, her double, Anita the Child Puppet, and interacts with her.[20]

The performance continues by switching back and forth between the representations of Hannah as an adult, child, and puppet. In one of the scenes, Anita the Child expresses her excitement at seeing the colorful sky in the past while Anita the Adult in the present gives context to the experience, explaining that this was actually the beginning of the war:

ANITA THE CHILD: (Pointing up towards the sky) Hey! look! The skies are orange! It is probably the fireworks celebrating the queen’s birthday! So beautiful!

ANITA THE ADULT: (Looking at the audience) I was seven when my mother stormed into our room screaming: “Miriam, Anita, Alexandra! Get away from the windows! WAR! WAR! It was in May 1940… (O’Donovan 2003: 8:22-9:03)

The performance conveys the child’s perspective of the confusion and chaos of war, while the adult’s narrations provide historical context. As the performance progresses, Anita’s confusion becomes more specific, representing her experiences as a Jewish girl who was labeled as “other” under Nazi laws. In these scenes, adult logic cannot make sense of the situation, and the exploration of identity is portrayed by puppets when Anita the Child expresses her confusion about the racial law in a dream scene in which she is playing with dolls.

Puppets Play with Dolls: Perspective on Identity

In the opening scene, Anita the Child character introduces her dolls and continues to play with them throughout the performance. While Anita the Child Puppet is made of wood, her dolls have different designs and are typical store-bought toys. Winnicott (1980) pointed out that when a child plays with an object or a doll, the act of playing helps them bridge between two parallel realities: inner Subjective Reality and outer Realistic Reality. By playing, the child expresses their subjective reality and explores the norms of realistic reality. Playing helps to find meaning, emotional resilience, certitude and comfort in transitional times laden with changes and chaos. By playing make-believe games with dolls, Anita the Child tries to find meaning in realistic reality, interpreting and exploring the loss of reason with the life-threatening racist laws. One powerful example is a scene when a puppet of Hitler appears in Anita’s dream, performing a selection of her dolls, a reference to the segregation of Aryans from Non-Aryans, throwing away all the “different” dolls:

HITLER: (Picks up a turtle doll) Let’s see what we have here…what is your name?

TURTLE DOLL: Zarathustra

HITLER: Zarathustra, Eh?! Let’s see… this is obvious… You are entirely different. Therefore, you are probably a Jew! Yak! (Throws him over to the left, takes a new doll.) Come here! What is your name?

BEAR DOLL: Bongo

HITLER: Bongo? Ok… and what do you eat, Bongo?

BEAR DOLL: Honey

HITLER: Honey?! Yuck! Don’t you eat apple strudel?

BEAR DOLL: No… just honey.

HITLER: Honey! This is not normal to eat honey—disgusting! (Throws him over to the left, takes a new doll.)… And you? Who are you? Come here! (O’Donovan 2003: 45:58- 49:12)

The performance continues with other dolls, including a black doll with the “wrong” skin color and a giraffe with a “too-long” neck. In contrast, when Hitler picks up a blond Aryan-looking doll, he adores her, kisses her, and keeps her on his right side. When the pile of dolls scene ends, Hitler faces Anita the Child:

HITLER: And, you! Who are you?

ANITA THE CHILD: I am Anita, and don’t ask me anything about who I am or what my name is… nothing! I want to tell Lotte who I am. I want to tell her everything! But I can’t! Everything is a secret! And it is all because of you! (O’Donovan 2003: 48:41- 49:04)

As the daughter of a Christian father and a Jewish mother, Anita’s mixed identity places her in a highly complex position under the racist laws, threatening her very being. This tension is expressed in a wordless segment where Anita the Child examines her body and applies yellow stains to parts that are different from each other. This deconstructs her body into two elements—one Jewish, the other not. The act concludes when she paints her right-hand yellow and places it on her chest as a symbol of the Judenstern (“Jew’s star”), the yellow badge that Jews were ordered to wear by the Axis powers. The child Anita is positioned between her two puppet-like hands, unable to escape the confines of her identity as defined by the racist laws. Using puppetry to separate her body parts, Anita highlights the absurdity of racism and the conflicting emotions experienced by a child torn between the two contradictory aspects of her identity (Levitan 2013, 12-14).

Ian’s Daughter employs both documentary narrations to convey the story and fragmentary material-images to express the traumatic experiences. The factual components of the performance are conveyed through the Remembering Self, Anita the Adult, who provides a verbal narrative that includes names, dates, and historical context. The fragmented elements are expressed through the Experiencing Self, Anita the Child and Anita the Child Puppet, depicting her confusion and fractured identity. This duality of presentation creates a reflective aesthetic that centers on the confrontation with the past, rather than on the past itself.

A more intense exploration of identity and facing the past can be found in Otherwise.[21]

Otherwise: Deconstruction and Repair

Otherwise tells the childhood story of Hava Nissimov who was born as Eva Altchiler in Warsaw, Poland, on 9 June 1939, less than three months before the German invasion in September. In November 1940, the Germans confined the city’s Jewish residents to a crowded ghetto, where Hava’s father became fatally ill with typhus. After his death, her mother was successful in escaping with Hava from the ghetto. They spent a few months hiding in Warsaw, but as Hava became older, it became more difficult to hide in the city. She was sent to the countryside home of a non-Jewish Polish family where she was hidden in a dark, narrow space behind a closet. When the war ended, Hava was reunited with her mother, whom she did not recognize. She never spoke about her harrowing childhood experiences until she was forty, when she suffered from a severe anxiety disorder. In the wake of her emotional challenges, Hava started to deal with her traumatic childhood memories by writing poems and books and sharing her story in numerous venues.[22]

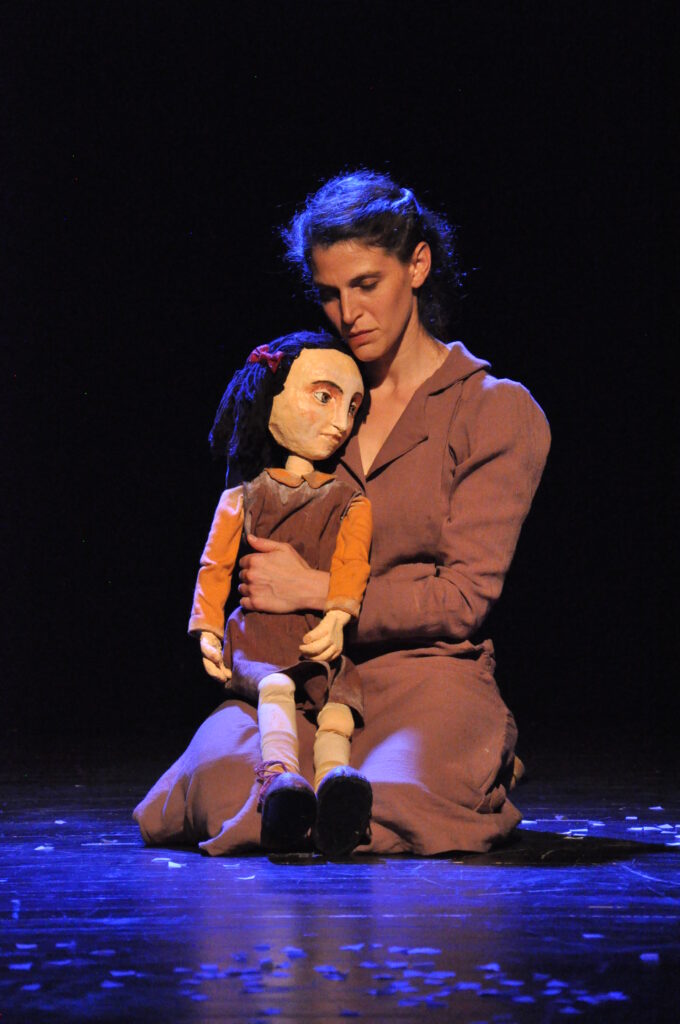

After years of repeatedly sharing her story, Nissimov began to feel she was sounding like a broken record. Seeking to reconnect with her own story, she contacted puppeteer and director Elit Veber with a request to create a puppet that would assist her in conveying her story.[23] Veber proposed to develop the project beyond mere puppet-making to adapting the story into a full puppetry performance. In an interview, Veber shared that working on Hava’s childhood story was different from her previous works, as it was the first time she was dealing with a sensitive biographical story of a living person who also took part in the creative process. Veber was attentive to the aesthetics in which Hava’s story would be presented, leading her intuition to create a reflective aesthetic of the memory using the puppetry doubling technique (Veber 2021). The resulting performance was aptly titled Otherwise.[24]

Puppets and Puppeteer: A Perspective on Time, Place, and Experience

The doubling technique employed in Otherwise involves several portrayals. The protagonist is Hava as an adult character reflecting on her past memories. Her character is divided into two sub-representations:

- Hava the Adult – a puppeteer actress who embodies Nissimov as an adult Remembering Self, reflecting on her childhood memories. Sometimes she steps into the role of other characters, including her mother and her younger self.

- Hava’s Voice – a recording of Nissimov’s actual voice sharing selected fragments of her childhood memories.

The reflection of the past events is depicted through two portrayals of the child Experiencing Self:

3. Hava the Child Puppet – a puppet representing Hava as a child.

4. Hava the Child Animation – an animation of Hava the Child Puppet projected on a screen at the back of the stage, providing insightful perspectives on various situations throughout the performance.

Like in Ian’s Daughter, Otherwise begins with a prologue that creates a perspective on the act of remembering. On the stage a young woman sits inside an antiquated closet, playing with a baby. Similar to Ian’s Daughter, the opening scene of Otherwise also includes a depiction of the protagonist’s hometown. In this case, the description is complemented by a background song written by Nissimov, which vividly depicts her version of Warsaw in the summer of 1939 as a joyful and beautiful city. While Ian’s Daughter includes specific details about the Dutch village, in Otherwise, the protagonist, who was only three months old when the war began, provides an idealized portrayal of the place of her birth. This idyllic atmosphere shatters as flashing lights and deafening sound-effects illustrate bombing, while the young woman in the closet tries to protect the baby puppet. The prologue ends with the stage darkening, the closet door closing, and a recording of Hava’s Voice playing in the background. In the recording, she shares early childhood memories of being a baby during the war and almost being hit by German munitions.

As the stage lights come back on, the puppeteer who sat in the closet, steps back onto the stage and portrays Hava the Adult. She stands beside the closet, staring intently at it. After a moment of hesitation, she opens the closet door, pulls out a drawer, and takes out old photographs, regarding them with a pained expression. She touches the clothes hanging in the closet and takes out a jacket, smelling it with sorrow, and in a decisive moment, she puts on the jacket. Her posture changes and she becomes her young mother during the war. Now, as her mother, she wears a hat and walks quickly behind the closet, returning with a puppet in the form of a young girl—Hava the Child Puppet. Hava the Adult (who is now embodying her mother’s character) places Hava the Child Puppet next to her, while in the background Hava’s Voice recounts her memories from her early childhood days living in the ghetto:

I’m walking with my mother on the street which is terribly crowded. Gray people sit on sidewalks leaning against the wall. Even children stretch out their hands. A cart full of dead bodies rolls over the pavement. An old man crouches on the cart above other people, his white hair dragging the stones. I see everything. (Veber 2014)

As Hava’s Voice describes the memory, both Hava the Child Puppet and Hava the Adult relive the experience, and follow with their eyes the rolling cart of dead bodies. Hava the Adult covers Hava the Child Puppet’s eyes to shield her from the harsh sights. Then, overwhelmed by the memory, Hava the Adult tries to shake off the memory. She removes her jacket, shedding the image of her mother, and then approaches the closet to return the jacket and closes its doors. Then, when she sees Hava the Child Puppet sitting lifeless on the stage, she pauses. Suddenly, filled with renewed vitality, she approaches the closet and retrieves a suitcase.

The closet, representing the same one Nissimov hid behind during the war, holds her memories, and when Hava the Adult opens its doors, the objects she finds trigger her memories. Otherwise is skillfully structured in a way that every object evokes a new fragment of childhood memory. The sight of a jacket evokes the memory of her mother, a fabric inside the suitcase evokes the memory of her father’s death in the ghetto, and a childhood hair tie triggers memories of her cousin who was sent to Auschwitz. Hava the Adult engages with the memories in the closet, as the audience witnesses how she confronts her memories, some of which she immediately blocks by closing the closet’s door, while others she chooses to explore in depth. One experience that is confronted upfront is her split identity.

Puppets Play with Dolls: Perspective on Identity

The language of imagery and materials used in puppetry provide a powerful medium to portray intricate emotions experienced by children in hiding. In Otherwise, this complexity is expressed through multiple versions of Hava the Child Puppet representing her physical growth and emotional state as the play unfolds. Hava’s representation as a child puppet changes in height: her legs become extended, representing her physical growth; in volume: appearing as a 2D shadow, expressing the three years of hiding in the dark in the narrow space behind a closet; and in size: appearing as a miniature that can be held on the palm of a hand, representing her helplessness and vital need not to be found in order to survive. Another striking change in Hava’s representations is the transformation of Hava the Child Puppet’s identity from a Jewish girl to a Christian girl.

As in Ian’s Daughter, the deconstruction of identity is represented by a split body. Hava the Adult, embodying her mother’s caricature, attempts to train Hava the Child Puppet to become a devout Christian Polish girl, teaching her how to do the signum crucis (sign of the cross). When Hava the Child Puppet fails to make the right movements in the tracing of the shape of a cross, her mother looks sadly into the puppet’s eyes, touches the puppet’s black hair, and suddenly exchanges the puppet’s head with a new gentile-looking head, complete with blond hair, transforming the Jewish Hava the Child Puppet into a Christian-looking girl. At that moment, Hava’s Voice is heard, saying:

Starting today, I am a new girl. Polish. Christian. I am not allowed to tell anyone that I am Jewish. I have a completely new name. Starting today, my name is Eva Olenska … (Veber 2014)

Veber explains this theatrical decision:

Hava told me that when they dyed her hair blond and sent her to the village as a Christian girl, she felt like she was a different girl […] And it was a question of how to express, not only the action but rather her deep, strong feelings. How can I change her identity on stage? I was thinking about how to switch the hair, but then the richness of theatrical language provided an answer—I should not change the hair—but cut off the whole head! I should not try to hide it like it’s magic; no, it should be upfront. Everyone should see it. […] because her identity was cut off from her. (Veber 2021)

In the chaotic scene where Hava the Child Puppet undergoes a dramatic identity transformation, an animated representation of her, Hava the Child Animation, is projected in the background, acknowledging the pain of the moment. This portrayal of multiple representations of Hava as both a fragmented puppet and a whole animated figure who reflects on her pain demonstrates the reflective method, expressing the deconstruction of identity while maintaining a sense of self. This method appears in a later scene where Hava the Child Puppet plays with another representation of herself as a doll.

After hiding, the Christian-looking Hava the Child Puppet receives a doll as a gift from her mother, who is hiding in a different locale. Hava’s Voice explains that when she received the doll, the son of the Polish family where she was hiding ripped off the doll’s head. On the stage, the Christian-looking Hava the Child Puppet makes a failed attempt to reconnect the doll’s head back to its lifeless body. The puppeteer, Hava the Adult, bemoans the sight of the torn head and places a ribbon on her own hair, mirroring the ribbon in the doll’s hair. At that moment, Hava the Adult transforms into embodying herself as a child, who playfully interacts with her double, a headless doll.

In the beginning, Hava hugs and kisses the headless doll, manipulating the doll to jump and clap her hands. Suddenly she makes the sound of a knock on the door, and with an angry look, she places her finger on the doll’s lips indicating that the doll must keep quiet! Then she places the headless doll in a hiding place behind a box she uses as a closet. She then picks up Hava the Child Puppet, and in a scene of mirroring her mother, she attempts to teach the puppet to trace the movements of the sign of the cross. When Christian-looking Hava the Child Puppet fails, Hava becomes angry, yelling and dragging the puppet into a sack on the stage. This is the same sack in which Hava the Child Puppet was stowed in a previous scene when she was transported to hide in the home of the Christian family. The scene ends when Hava opens the sack to dispose of the Christian-looking Hava the Child Puppet, but surprisingly, she finds in the sack the original “Jewish-black hair” head of Hava the Child Puppet. When Hava sees herself in the decapitated head of the puppet, she stops playing the game, removes the ribbon from her hair, and transforms back into being Hava the Adult.

Dolls served as a lifeline for children who survived the Holocaust, cut off from their biological parents. The solid objects provided a connection to their family and helped them in maintaining a sense of identity and belonging to their heritage (Dori 2020: 19-20). The deconstruction of the doll head, which was given as a gift from the mother, represents the acute separation, not only from her biological mother, but also from her identity and her childhood. Dolls and puppets, unlike children, do not need to follow expected behavioral norms. As external objects, they permit children to project their deepest feelings and fears and negotiate different internal voices and pieces of their identity (Cooper-Caesari 2014). Similarly, the use of dolls in Ian’s Daughter, when Anita the Child plays with dolls, exemplifies her confrontation with her split identity. In Otherwise, the deconstruction of identity is vividly expressed through these dolls. The representations essentially multiply as the doll doubles the puppet, which doubles the puppeteer. This deconstructed representation expresses the vulnerability of the child and the fragmentation of identity. At the same time, the multiplicity of representations allows the Remembering Self, Hava the Adult, to witness herself, a gaze that, according to Jacques Lacan’s Mirror Stage concept, leads to the development of a sense of self and identity formation.[25]

Otherwise is woven together with documentary and fragmentary elements, combining Hava’s real voice as a narrator and her character as an adult with splintered images of herself as a child. The combination of the two genres forms the reflection on memory.

Insights: The Endings

In this paper, I have exemplified how puppetry’s doubling technique allows for a clear differentiation between the actual experience and the way that the experience is remembered. This technique enables the expression of both fragmented identities and a cohesive narrative that exists within a specific time and place. The use of puppetry’s abstraction allows a more nuanced exploration of memory and identity, while the accompanying narration of the puppeteer anchors the abstraction within a specific time and place, with a clear beginning and, more significantly, a clear ending. Kahneman and Riis’s theory of Two Selves highlights the ending moment of an experience as a remarkable influence on how the experience is remembered. This means that even if an experience was positive but ended poorly, the memory of the entire experience would be unpleasant. Inversely, an unpleasant experience can be remembered as relatively positive, if it ended on a good note (Kahneman and Riis 2005). Therefore, it is important to pay attention to the structure of performances and to carefully examine how the performances end.

Both performances begin with a prologue that reflects on the act of remembrance and contains a description of the protagonists’ hometowns.[26] Both performances also end with similar scenes describing the hometowns, but with slight changes that signify the transformation of the protagonists’ relationship with their past. In the final scene of Ian’s Daughter, Anita the Adult is depicted as bending over a collection of messy little wooden houses that symbolize her childhood village, which was raided by the Gestapo on the night her family escaped. She rearranges the little wooden houses in a symbolic attempt to rebuild the village, in effect restoring the disorder that she remembers on the night when she escaped.

While she places the little wooden houses, she repeats the same description of the village that was used in the opening scene. This time, her words carry a different meaning as she is not introducing the village but rather parting from it.

Lotte remains in my memory as the good friend I had during those years before the war. When all the houses looked the same, the bike paths… the little backyards… like in the days when Lotte and I used to meet and walk together along the canal to the school. And on the way back, every time we crossed the canal, we climbed on the bridge and looked at the water flowing beneath us… and kept flowing… (She looks at the village. Light fades. End of the performance). (O’Donovan 2003: 56:21 – 57:51)

Anita the Adult looks upon her once beloved childhood village. Her mention of the canal’s flowing water literally and metaphorically symbolizes the passage of time, representing the continuity of life toward the future. This idea contrasts with the circular experience of trauma, where the past repeatedly resurfaces and disrupts the present.

In Otherwise, the performance concludes with the same song that opened it, which describes a city full of beauty and joy and with the same image of a woman holding a child in her arms. However, there is a noticeable difference between the first and final scenes. In the first scene, the song includes a description of the war and ends with the words, “And I was born.” In the final scene, the song omits the war description and from the joyful city and concludes with the words, “And I was born.”

In the opening scene, there is a woman holding a baby inside a closet and in the final scene the closet that held the memory is empty, with its doors wide open, signifying that there are no more secrets to hide. Outside the closet, Hava the Adult is seen holding herself, Hava the Child Puppet, in the same position as the mother holding the baby from the earlier scene. In the background screen, Hava the Child Animation looks on at the scene, providing recognition of the ongoing complexity of the past in the present. The performance ends when Hava the Child Puppet, who had been unaware that Hava the Adult was her puppeteer throughout the whole performance, suddenly looks at Hava the Adult, recognizes and embraces her. This final moment represents a reconciliation between the Two Selves and a coming to terms with the traumatic past.

The final moments of both plays do not try to lessen the impact of these challenging stories, as they do not provide a simplistic or contrived happy ending. Instead, they are portrayed as a significant step towards acknowledging the past, processing loss, and seeking purpose in the present.

In today’s world questions of identity are prevalent, and memories of traumatic experiences and painful pasts hold significant importance. By employing the puppetry doubling technique, these performances provide a reflective perspective that enables audiences to cultivate a more nuanced understanding of the past, navigate and process challenging narratives, and develop a deeper and more complex relationship with them.

[1] Members of American Society for Theatre Research puppetry working group, as well as Association for Jewish Studies graduate students helped refine this paper. I would like to thank Patricia O’Donovan and the reviewers of this paper for their valuable comments. A special thanks to Gene Plunka for his encouragement and advice.

[2] The analysis is based on watching private recorded versions of the performances and conducting interviews with the creators. Both performances are now accessible for viewing on YouTube. See the specific links for each performance given when the plays are discussed later in the paper. All dialogues from the performances have been translated into English by the author.

[3] The artistic techniques used to depict the past have been the subject of extensive academic literature across various forms of media, including literature and film. Scholars like Gérard Genette (1980) have analyzed narrative discourse in fiction and film, with a focus on the “metadiegesis” aesthetic, which involves a story being told within another (outer shell) story. Robert Alter has examined novels that challenge traditional modes of representing reality by employing self-aware playfulness instead of realism (Alter 1975).

[4] Amelia Ran (2016, 6-9) quoting from: John Dewey (1933, 12).

[5] Puppetry has been used in Holocaust performances in Israel since the 1980s. For example, the play Uncle Arthur (Dod Arthur) by Danny Horowitz (premiere: Beit Lessin, Tel Aviv, 1981) features a Holocaust survivor who uses puppets to tell his story after theatres refused to stage his play. Similarly, puppets play a significant role in Joshua Sobol’s play Ghetto (premiere: Haifa Municipal Theatre, 1984), where a character employs puppets to convey the truth about the situation. These performances, however, did not utilize reflective doubling techniques. Read more on these two performances in Horowitz (2017) and Rokem (2002 and 1988).

[6] Olga Levitan (2013) gave an overview of the evolution of puppetry in the twentieth century; see also Ophrat (2008, 102-119) and Francis (2012, 121-145).

[7] Rycroft is further cited and discussed in Pendzik, Johnson, and Emunah (2016, 1-18).

[8] Eliezer Ben-Yehuda, one of the driving forces behind the revival of the Modern Hebrew language, crafted the word bubah (בובה) inspired by the French word poupée. He defined bubah as “the figure of a girl or woman, resembling a small play thing for little girls.” Read more: The Academy of Hebrew Language (2023). In Hebrew, there are not distinct words for “doll” and “puppet.” Therefore, puppetry is inherently associated with children. I thank Patricia O’Donovan for sharing this observation with me.

[9] See Mello, Orenstein, and Astles (2019, 6). Gross (2019, 11) also mentions how “puppet” was used to describe sex workers and has negative associations.

[10] Pupa is the term used in etymology to describe the stage in the development of holometabolous insects between the mature larva and the adult, wherein major morphological reorganization occurs. (See Stehr 2009, 862-863.) Bubah is linked to the Aramaic word bava (בָּבָא) meaning “gate” (The Academy of Hebrew Language, 2023). Insa Fooken and Jana Mikota (2018, 43ff) demonstrate in their research how the transformation from childhood to adult is shown through play with dolls. Girls usually stop playing with dolls around the age of thirteen to fourteen years. Adolescent girls in ancient Greece sacrificed their favorite doll as an oblation to one of the principal female Olympian Goddesses—Hera, Aphrodite, or Artemis. The cessation of playing with dolls became a significant transitional phase that expressed that they were ready for marriage.

[11] Diaries include Het Achterhuis (The Annex-The Diary of a Young Girl/Anne Frank) and The Diary of Éva Heyman; some films are La Vita è Bella (Life is Beautiful, 1997) and The Book Thief (2013); and there are many books (see Milner 2008).

[12] In the past twenty years, several puppetry performances in Israel dealt with the experiences of Holocaust child-survivors in hiding. Examples include My Hugo (Ronit Kanu and Naomi Yoeli, 2021); The House by The Lake (Yael Rasooly and Yarra Golding, 2012); and The Little Home in a Barrel (Adam Yakin, 2014).

[13] Yakin is Hannah’s married name.

[14] On 29 September 1997, Yad VaShem recognized Ian van Hulst [using the spelling Jan van Hulst] as Righteous Among the Nations: See the Yad-VaShem website: https://righteous.yadvashem.org/, accessed 24 April 2023.

[15] O’Donovan was Born in Buenos Aires to parents who immigrated to Argentina in the 1940s. Her father was a non-Jewish mathematician and chess master from Ireland and her mother was a Jewish artist who fled Vienna due to the Nazi occupation. For more on O’Donovan’s puppet work see O’Donovan’s website: https://www.patriciaodonovan.com/, and Foley (2012) at https://wepa.unima.org/en/patricia-odonovan/, both accessed 24 April 2023.

[16] Olga Levitan analyzes the theatre-within-theatre language in Ian’s Daughter as a key method to deliver the story to child audiences (2013: 12-14).

[17] Information on the production is from my interview with Patricia O’Donovan in 2021. The first performance, entitled Passe Compose was at the 2002 Méli’môme Festival in Reims, France. This title emphasized the continuous complex experience of time and memory. The title was later changed to Ian’s Daughter for Israeli audiences. The analysis of this performance is based on the creator’s private recording (see O’Donovan 2003), as well as interview (O’Donovan 2021).

[18] In an email (11 June 2023), O’Donovan mentioned that in the initial performances, the audience mistook “Hannah” for “Anne Frank.” To avoid confusion, she changed Hannah’s name to “Anita.”

[19] The blueprints of the village and the family house are based on Yakin’s drawings.

[20] Anita the Child puppet and her family were created from repurposed chair legs, with a simple design including wool hair and painted eyes. O’Donovan’s choice to use broken wood collected from the street and give them a new life symbolizes the survival of the family that endured the Holocaust (O’Donovan 2021).

[21] Ian’s Daughter was created specifically for children, whereas Otherwise was intended for adult audiences. Although the role of the audience in shaping the performance is significant, that element is not discussed in this paper.

[22] In 2007, Nissimov published a book containing fragments of her childhood memories. Hava Nissimov, A Girl from There (2007) and in 2015 it was translated into English by Linda Zisquit. Nissimov recorded her memories as stories and poems in other books including Home is Homeless (2008); My Joy Dances Gently (2014); Kaleidoscope (2015); Florian’s Secret (2017); and Flamingo (2019).

[23] Veber is an Israeli-born artist and therapist. In her work, she explores the expressive possibilities of puppet and puppeteer relationships. More on Veber’s puppetry work see: https://he.wikipedia.org/wiki/%D7%90%D7%9C%D7%99%D7%AA_%D7%95%D7%91%D7%A8, accessed 22 June 2023.

[24] Otherwise premiered at the 2014 International Festival of Puppet Theater and Film in Holon, Israel. The analysis in this article is based on the recording of the performance (https://youtu.be/p8jVIe4Bwto), accessed 30 July 2023; an interview with Veber (2021; and by studying Veber’s original manuscript (Veber 2014).

[25] Lacan’s Mirror Stage concept distinguishes between the physical body (I-self) and the perceived image (myself) in the mirror, which is a key step leading to the development of a sense of self and forms one identity.

[26] Brain researchers have noted the significance of locality in the storage and retrieval of memories. An example of this observation is demonstrated in Edvard and May-Britt Moser work (2013).

References

The Academy of Hebrew Language. 2023. “Doll and Fairy in Masculine?”16 January. https://hebrew-academy.org.il/2016/02/23/%d7%91%d7%95%d7%91%d7%94-%d7%95%d7%a4%d7%99%d7%94-%d7%91%d7%96%d7%9b%d7%a8/, accessed 15 June 2023.

Aldouby, Achinoam, and Dalia Goldfarb-Zarchin. 2020. “Theatrical Works about and by Women during the Holocaust” [Hebrew]. Bamah – Israeli Performing Arts Magazine 286: 372-390. [Special Issue, Life or Theatre: Women and the Theatre of the Holocaust, ed. by Moti Sandak. Tel Aviv: The Institute for Jewish Theater].

Alter, Robert. 1975. Partial Magic: The Novel as a Self-Conscious Genre. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Barzel, Hillel. 1995. Drama of Extreme Situations: War and Holocaust [Hebrew]. Tel Aviv: Poalim.

Benjamin, Walter. 2003. “On the Concept of History.” In Walter Benjamin: Selected Writings. Vol. 4, 1938-1940, ed. by W. Jephcott, H. Eiland, and M.W. Jennings, 389-400. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press.

Chittooran, Mary M. 2015. “Reading and Writing for Critical Reflective Thinking.” New Directions for Teaching and Learning, 143: 79-95.

Cooper-Caesari, Smadar. 2014. “Zoom into Puppet—The Three-dimensional Model of the Puppet: Therapeutic Aspects.” Academic Journal of Creative Art Therapies 4, No. 1 (June): 407-415 [Haifa: Haifa University].

Dewey, John. 1933. How We Think: A Restatement of the Relation of Reflective Thinking to the Educative Process. Chicago: Henry Regnery and Co.

Dori, Nitsa. 2020. “Children’s Toys and Games during the Shoah, as Reflected in Five Hebrew Books.” Journal of Education and Training Studies 8, No. 5 (May): 17-29.

Favorini, Attilio. 2008. Memory in Play: From Aeschylus to Sam Shepard. New York: Palgrave MacMillan.

Feingold, Ben-Ami. 2012. Theme of the Holocaust in Hebrew Drama (1946-2010). Tel Aviv: Ha-Kibuts Ha-meʼuḥad.

Francis, Penny. 2012. Puppetry: A Reader in Theater Practice. NY: Palgrave Macmillan.

Foley, Kathy. 2012. “Patricia O’Donovan.” World Encyclopedia of Puppetry Arts. https://wepa.unima.org/en/patricia-odonovan/, accessed 30 May 2023.

Fooken, Insa, and Jana Mikota. 2018. “‘Help Me to See Beyond,’ Dolls and Doll Narratives in the Context of Coming of Age.” In Dolls and Puppets: Contemporaneity and Tradition, ed. by Kamil Kopania, 36-53. Biał ystok: Aleksander Zelwerowicz National Academy of Dramatic Art [Warsaw], Department of Puppetry Art [Białystok]. [See also https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Kamil-Kopania/publication/341642130_Dolls_and_Puppets_Contemporaneity_and_Tradition/links/5eccd1b392851c11a88ab0ab/Dolls-and-Puppets-Contemporaneity-and-Tradition.pdf, accessed 30 May 2023.]

Genette, Gérard. 1980. Narrative Discourse: An Essay in Method,trans. by Jane E. Lewin. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Guedj, David, and Ofer Shiff, eds. 2022. The Holocaust and Us in the Israeli Theater . [Hebrew]. Sde Boker: The Ben-Gurion Research Institute for the Study of Israel and Zionism.

Gross, Kenneth. 2019. Puppet: An Essay on Uncanny Life [Hebrew], trans. by Zaira Gutesman. Haifa: Pardes.

Horowitz, Danny. 2017. “Talk on the Play Uncle Arthur, Tel Aviv University Medical School.” 7 December. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sm3POyp-eOA, accessed 15 June 2023.

Kahneman, Daniel, and Jason Riis. 2005. “Living, and Thinking About it: Two Perspectives on Life.” In The Science of Well-Being, ed. by Felicia A. Huppert, Nick Baylis, and Barry Keverne, 284-305. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Kaynar, Gad. 1998. “The Holocaust Experience through Theatrical Profanation.” In Staging the Holocaust, ed. by Claude Schumacher, 53-69. Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Press.

LaCapra, Dominick. 2006. Writing History, Writing Trauma [Hebrew], trans. by Yaniv Farchash and Amos Goldberg. Tel Aviv: Resling.

Levitan, Olga. 2013. “Puppet as an Instrument of Thought.” In Theatre For Children—An Artistic Phenomenon, ed. by Henryk Jurkowski and Miroslav Radonjic, 6: 5-39 [Subotica, Serbia: Open University].[See also https://www.academia.edu/6005294/THE_PUPPET_AS_AN_INSTRUMENT_OF_THOUGHT, accessed 30 May 2023.]

Malkin, Jeanette R. 1999. Memory-Theater and Postmodern Drama. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

Martin, Carol. 2012. “Apart From the Document: Jews and Jewishness in Theater of the Real.” In Jews and Theater in an Intercultural Context,ed. by Edna Nahshon, 165-196. Leiden, Boston: Brill.

Mello, Alissa, Claudia Orenstein, and Cariad Astles, eds. 2019. Women and Puppetry: Critical and Historical Investigations. London: Routledge.

Milner, Iris. 2008. The Narratives of Holocaust Literature [Hebrew]. Tel Aviv: Hakibbutz Hameuchad.

Moser, Edvard, and May-Britt Moser. 2013. “Grid Cells and Neural Coding in High-End Cortices.” Neuron 80, No. 3: 765-774.

O’Donovan, Patricia. 2003. Ian’s Daughter [Private recording of the performance]. Patricia O’Donovan [See also Website] https://www.patriciaodonovan.com/, accessed 13 June 2023.

_____. 2021. Personal Interview, 21 July.

_____. 2023. Personal Email, June 11.

Ophrat, Hadas. 2008. Conversations with a Puppet: On Contemporary Puppetry [Hebrew]. Tel Aviv: Sal Tarbut Artzi Publishing.

Nissimov, Hava. 2007. A Girl from There. Sde Warburg: Mikteret. [English trans. (2015) by Linda Zisquit. New York: KTAV Publishing House].

_____. 2008. Home is Homeless [Hebrew]. Tel-Aviv: Aked.

_____. 2014. My Joy Dances Gently [Hebrew]. Tel-Aviv: 77.

_____. 2015. Kaleidoscope [Hebrew]. Tel-Aviv: Miskal.

_____. 2017. Florian’s Secret 2017 [Hebrew]. Tel-Aviv: Miskal.

_____. 2019. Flamingo [Hebrew]. Haifa: Pardes.

Pendzik, Susana; David Read Johnson; and Renée Emunah. 2016. “The Self in Performance: Context, Definitions, Directions.” In The Self in Performance: Autobiographical, Self-Revelatory, and Autoethnographic Forms of Therapeutic Theater, ed. by Susana Pendzik, David Read Johnson, and Renée Emunah, 1-18. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Plunka, Gene A. 2009. Holocaust Drama: The Theater of Atrocity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

_____. 2018. Holocaust Theater: Dramatizing Survivor Trauma and Its Effects on the Second Generation. New York: Routledge.

Ran, Amelia. 2016. Reflection: Thinking Fast and Slow in Education. Tel Aviv: MOFET Institute.

Rokem, Freddie. 1988. “On the fantastic in Holocaust performances.” In Staging the Holocaust, ed by Claude Schumacher, pp. 40- 52. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

_____. 2002. Performing History: Theatrical Representations of the Past in Contemporary Theatre. Iowa City: University of Iowa Press.

Rycroft, Charles. 1983. Psychoanalysis and Beyond. London: Chatto & Windus Hogarth Press.

Schumacher, Claude, ed. 1998. Staging the Holocaust. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Skloot, Robert. 1988. The Darkness We Carry: The Drama of the Holocaust. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press.

Stehr, Frederick W. 2009. “Chapter 216 – Pupa and Puparium.” In Encyclopedia of Insects (Second Edition). East Lansing: Michigan State University.

Veber, Elit. 2014. Otherwise, Draft 6 [Unpublished play script].

_____. n.d. Otherwise, [Private recording of the creators].

_____. 2021. Personal Interview. 4 December.

Winnicott, Donald. 1980. Playing and Reality. London: Tavistock Publications.

Yad Vashem. n.d. [Website]. https://righteous.yadvashem.org, accessed 30 May 2023.

Yakin, Hannah. 2015. On Tortoise and Other Jews [Hebrew]. Jerusalem: Printiv.