The King’s Dream. Created and performed by Michael Schuster, music performed by Rachel Saul. ARTS at Mark’s Garage, Honolulu, Hawai’i, 21 and 28 May 2023.

Compelled by isolating pandemic years, puppeteer and storyteller Michael Schuster plunged into creativity. He researched, wrote, and built The King’s Dream, an intimate nineteenth- century storytelling style performance based on the historical interactions between Hawai’i’s reigning monarch, King David Kalakaua, and Elias Abraham Rosenberg. Rosenberg was an Eastern European Jewish emigrant, who had arrived in Honolulu during the tumultuous years of 1886-1887, when the Hawaiian monarchy was under severe political pressure from the Missionary Party to sign what came to be known as the Bayonet Constitution, a legal muffling and overpowering of Hawaiian culture, language, and leadership. Rosenberg is not well-known in the Hawaiian community today, but in 1887 he became King Kalakaua’s official soothsayer. Rosenberg has been described by some as a charlatan and by others as a mystic. The King’s Dream explores the connections between history, genealogy, and folklore, while highlighting issues of colonialism, racism, and antisemitism.

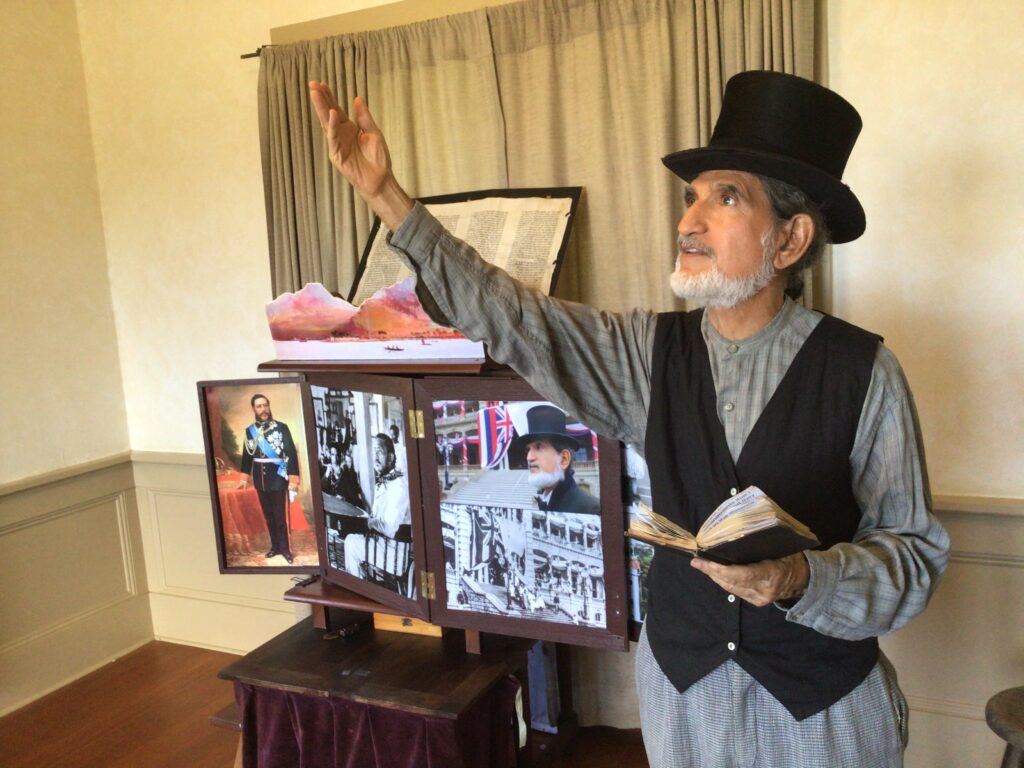

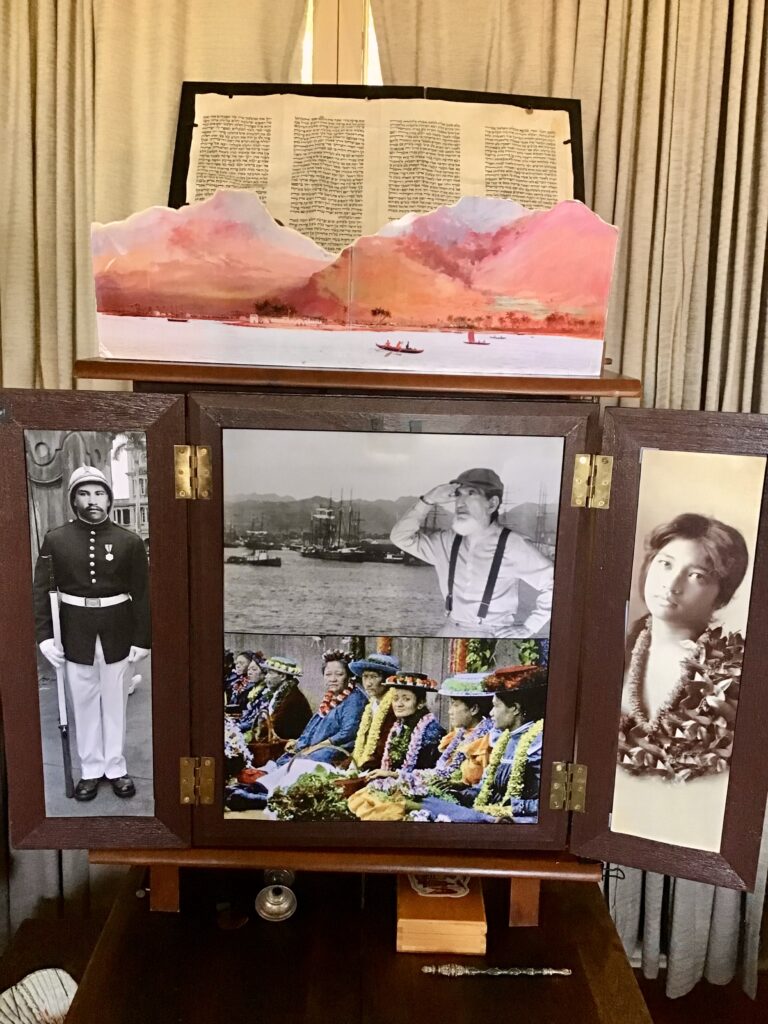

Schuster, in partnership with Troy Walden, constructed a unique, handcrafted storytelling cabinet, inspired by India’s Rajasthani kaavad tradition (a small cabinet that is a temple for storytelling) in order to dramatize the late nineteenth-century worlds of Kalakaua and Rosenberg (Figure 1). Schuster was introduced to the story-singing of these Rajasthani performers who chant of the Gods and the events depicted, and deliver family genealogies. He traveled to Rajasthan while working as a puppeteer-founder at the Train Theatre in Israel and he completed his Ph.D. dissertation on Indian puppetry at the University of Hawai’i. While in India he became aware and excited by the way itinerant story singers carry the ornately painted kaavads from house to house narrating tales and revealing new episodes by opening each successive panel/door.

The King’s Dream cabinet contained large-scale photographs taken during Kalakaua’s reign, along with contemporary photographs and documents that recreated historical events (Figure 2). Jewish ritual objects were also used. As the story unfolds, the multi-layered cabinet opens to reveal evolving imagery while the storyteller invites the audience into the unlikely encounter between Hawaiian and Jewish culture through images, puppetry, acting, and music. Puppetry techniques were based on nineteenth-century picture storytelling, particularly Rajasthani kaavad storytelling, as well as figures inspired by shadow puppetry. A wide variety of objects were animated: photographs, an ancestor collage panel, floating angels, cattle, scarves, hats, google eyes, and photo-shopped images recreating historical scenes, along with authentic religious objects used in spiritual practice. By honoring the ancestors, personal genealogy, and the biblical story of Joseph, Schuster provided a cultural bridge for the storied encounter of Rosenberg and the King. The performance was accompanied by live music, bringing culture alive through Hawaiian art song from the nineteenth century, Hebraic chant, and traditional Yiddish klezmer. Opening chants by cultural practitioners of Hawaiian oli (chant) and Jewish nigun (wordless melody) introduced the piece.

The play was inspired by Schuster’s curiosity concerning two objects—the Torah and silver yad (Holy scroll and sacred pointer, respectively) that Rosenberg gifted to the King before his departure in 1887. Historically, the Torah and yad disappeared until they resurfaced in the 1960s and have since been housed on display in a glass case at Temple Emanu-El, the only Jewish house of worship built in the Hawai’ian Islands. In The King’s Dream, a sacred mystery unfolds as two cultures share their parallel journeys to sustain and uphold cultural and spiritual identity in the overpowering shadow of political intrigue and the desired erasure.

Jews in Hawai’i? For some audience members, this was, and is, an unknown presence. How and why did Rosenberg become the official soothsayer to the King? Two cultural narratives run throughout the piece. Schuster—aligned with his own cultural integrity as an artist, a Jew, and a non-Hawaiian—followed his sense of kuleana (responsibility) by asking for a review of the piece by local kumus (Hawaiian teachers, cultural practitioners) as a way of seeking permission to present and fictionalize this unusual encounter with truthfulness and respect. Permission was affirmed. Acknowledging his own ancestral journey, Schuster opened the piece invoking his relatives by name, honoring those who came before. He chants the Torah parshah (portion) that tells the story of Joseph in Egypt, the imprisoned Hebrew slave who became the Pharaoh’s official dream interpreter. (Of personal importance, this was the actual Torah portion Michael chanted for his Bar Mitzvah service ritual at the age of thirteen.) Because of Joseph’s acuity in foretelling a seven-year drought, the King of Egypt empowers him with leadership to serve the people of the land and Joseph is named the Prince of Egypt.

The ancestral and cultural narratives of the Jewish and Hawaiian peoples are resonant with one another. King Kalakaua had become a global ambassador opening Hawai’i to the world. Yet, back home, the dominant political influence of the so-called “Reform Party” or the “Missionary Party” increases in power and becomes the driving force to deny the cultural and spiritual expression of the Hawaiians by debilitating the leadership of the beloved King. Rosenberg, through his dramatized journal entries and accounts based on nineteenth-century newspaper articles and books, conveys his deep concern for the danger he sees the King facing. Kalakaua has shared a repeated dream with Rosenberg that speaks of reaching for and missing connection to a place of refuge. Understanding this, Rosenberg encourages the King to uphold Hawaiian cultural identity and spiritual ways. A resonance of mutual cultural and spiritual values are at play as Rosenberg and the King grow in shared understanding. Racism, colonialism, and antisemitism rise as Rosenberg is all too predictably called a “Holy Moses” and suspicious troublemaker.

A post-show circle was convened after each performance, inspired by hoʻoponopono (to live pono, make right, and share with aloha) (Figure 3). Thoughts, perspectives, and feelings were exchanged. The King’s Dream evoked many matters in our lives today. Questions arose about the historical Elias Abraham Rosenberg and his relationship to the King; to the King’s awareness of Jews at the time (which seemed to be virtually nonexistent). Issues of “belonging” and “cultural appropriation” were discussed.

Hawaiians expressed gratitude in learning of Rosenberg’s story, his relationship to King Kalakaua, and how the two bridged cultures. They spoke of the timely healing work: naming historical, cultural, intergenerational, and ancestral trauma with its impact on sense of self and cultural identity and the need for decolonizing language and thinking. Cultural trauma carries its own distinct histories and wounds. Members of the Jewish community, who felt blessed to live in Hawai’i, reflected on diasporic living, personal relationship to land and place, and sensitivities in interfacing with the Hawaiian root culture. Living pono with the aina (land) is a sacred responsibility held by the Hawaiian people. The members of the Jewish diaspora affirmed the ideal of kuleana to steward the land and live aloha. Conversations that followed The King’s Dream illuminated scars of colonialism, white racism, and antisemitism through a lens of aloha and Yiddish mentschlikhkayt (shared humanity) in the spirit of adding to an evolving understanding of the whole.

A small Rajasthani kaavad, inspiration for The King’s Dream storytelling cabinet sat in the performance space lobby (Figure 4). Curiosity had been expressed about its traditional cultural uses. Michael described how puppeteers carried the kaavad from house to house in the Indian villages, not only transmitting stories, blessings, mythologies, and teachings of the Hindu Gods and Goddesses, but also including and incorporating the personal genealogies of each family household they entered into. So it was with The King’s Dream. Audience members were invited to find their place in the story.

Marsha Gildin

New York City Independent Performance and Teaching Artist