The goal in studying Balinese wayang (puppetry) is to understand its traditions, aesthetics, philosophy, and innovations to create productions that appeal to contemporary viewers. Through family- and school-based training, students are taught kawi dalang (the creative art of the puppet master). At Institut Seni Indonesia (ISI, Indonesian Institute of the Arts) in Denpasar, curricular innovations have occurred and theory and practical work combine. Students’ final projects often favor contemporary wayang using new puppets, innovative stories, music, and manipulation techniques.

I Nyoman Sedana is a professor at the Indonesian Institute of the Arts (ISI) Denpasar, director of Balimodule, and head of PEPADI (Indonesian Union of Puppeteers) in Bali. He received an MA from Brown University and a PhD from University of Georgia and has performed in Asia, the US, the UK, and Europe. His research has been supported by Yale Institute of Sacred Music, International Institute of Asian Studies (Netherlands), Asian Research Institute at the National University of Singapore, ASF (Bangkok), Indian Council on Cultural Relations, Freeman Foundation, Asian Cultural Council, and University of California. He has published in Asian Theatre Journal, Puppetry International, Asian Music, Puppetry Yearbook, and is co-author of Performance in Bali (Routledge, 2007).

Introduction

Wayang is a traditional theatre of Indonesia and Malaysia which takes various forms in the different linguistic and cultural areas of the country. The Balinese variation is a shadow theatre, with the most normal form, wayang parwa, telling Mahabharata stories in local adaptations. It is imbricated in Hindu-Bali religious belief and accompanied by two to four genders (metallophone percussion instruments) in a show lasting about three hours with a solo dalang (puppet master) singing, manipulating, narrating, and speaking for all the figures. This essay will consider how we train students in this heritage art at Institut Seni Indonesia (ISI, Indonesian Institute of the Arts) in Denpasar. The goals of the art, literary sources, and current innovations of Balinese students are noted.

The Goals of Wayang

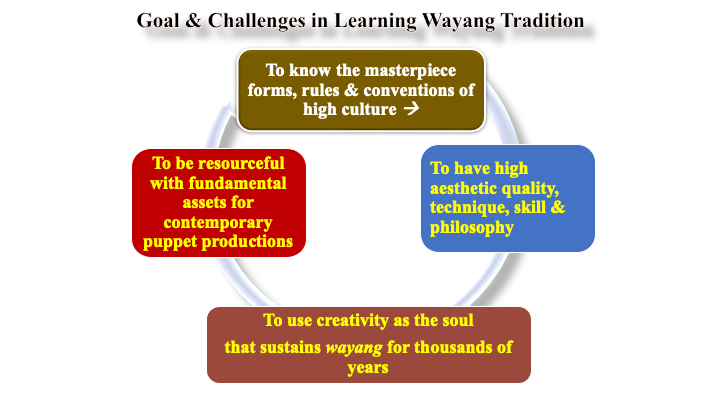

Wayang is a challenging art, be it traditional wayang parwa or the more recent wayang kontemporer, contemporary puppetry that adopts new stories and creates new styles of puppets and music. The latter form is favored by younger, ISI trained dalangs (puppet masters) for their graduation projects.[1] As discussed below (see Figure 1), becoming a dalang (puppeteer) can be broken into four major tasks: 1) mastering the tradition; 2) developing aesthetic quality, technique, and philosophy; 3) making creative innovations; and 4) maintaining popular appeal. Some of the new work at ISI responds primarily to the last two points, ensuring creativity and contemporary audience applause.

In learning the tradition, the first goal is to understand wayang kulit (leather shadow puppetry), which along with the many other forms of Indonesian wayang was declared a UNESCO Masterpiece of Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity on 7 November 2003.[2] Besides rigorous practice of music and manipulation, students must delve into literature to deepen their understanding. Works includes kekawins (narrative poems in Old Javanese/Kawi) such as Kakawin Ramayana (c.900 CE), Arjuna’s Meditation (Arjuna Wiwaha, c.1019 CE), Sutasoma (c.1370 CE), etc. Students must also absorb later literary works in Middle Javanese language macapat/sekar alit/pupuh meters. These poems are in verse forms with a tight pada-lingsa prosody that specify the number of syllables per line, the number of lines per verse, and the vowel ending of each line. Macapat and kakawin works are sung to set tunes and the verse forms of each are thought to have a specific emotional impact (sad, amorous, angry, etc.) for the dramatic character. They were and are often used to tell wayang narratives, to offer wise words and moral edification.

Additionally, students of wayang study Balinese language literary texts in forms like guguritan (a local narrative verse form), tutur and tattwa/tatwa—both the latter are religious/philosophical texts, which again often teach through narratives. Moreover, to understand the formulaic mantra that open and guide a performance, puppeteers study the Book of the Wayang Wisdom (Dharma Pewayangan), a text that was written on palm leaf manuscripts and passed down from one generation of dalang to the next and that provides philosophical, religious, and magical material (see Hooykaas 1973).

During my own training, as well as accessing old written materials at Gedong Kirtya, the major library of palm leaf (lontar) manuscripts in North Bali, and various published works in Bali that helped my study, I had the opportunity, on an International Institute of Asian Studies fellowship, to read a portion of the 2,892 entries on wayang in the Koninklijk Instituut voor Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde / Royal Netherlands Institute of Southeast Asian and Caribbean Studies (KITLV) library, in Leiden, where materials on Balinese and Javanese wayang have accumulated since the early colonial period. For the student of pedalangan there is no lack of written resources. At ISI as teachers, we urge our students to access written texts to expand on their oral-aural learning that their village guru provides.

Wayang has never been associated with the kind of child’s play that puppet performance is sometimes thought to be in the West. Firstly, wayang is studied for spiritual worth. It is a sacred heirloom and, in ritual practice, is thought to provide enlightenment and release entangled spirits from demonic traps through wayang’s aesthetic and ritual practices.[3] The French director Antonin Artaud, seeking the power of theatre as secular religion in Theatre and Its Double, pointed toward Balinese performance as a model (Artaud 1976: 104-116). Even an outsider like this French director could sense the energies Balinese activate in performance.

Today, ignorance about spiritual/philosophical benefits of the art among younger Balinese may discourage some students from studying wayang due to its lack of guaranteed economic success; nonetheless, professional specialization is possible. A very popular dalang, such as former ISI graduate Dalang Cenk Blonk/I Wayan Nardayana, manages to charge $2000 per night, which is a considerable fee on an island where $3350 is the average per capita earning in a year.

The second goal of wayang training is to develop aesthetic quality, technique, and philosophy. Besides requiring expertise in manipulation and music, traditional wayang demands the dalang have an excellent dramatic voice or rhetoric appropriate for each character, understanding of the dramatic repertoire, especially the local version of the Mahabharata (see Zoetmulder 1974, 68-98). The puppeteer succeeds by mastering speech, diction, humorous intermezzo, social criticism and commentary, music, puppet manipulation, and understanding the philosophy. While controlling the gender music via tapping the rattling side of the puppet chest (kotak) with his/her foot knocker, the solo dalang sings various songs while reciting dialogue and narration appropriate for the specific characters/scenes with correct puppet manipulation for each figure. These complex skills and the cost of acquiring the necessary apparatus (musical instruments and hundreds of leather puppets) are challenges for most students. Long hours in learning and significant economic resources for equipment combine to test the student’s mettle. Minor challenges include the cross-legged sitting, with the right foot on the top of the left thigh, on the floor in a position that is similar to a yoga pose. This stance is held throughout the hours of performance, while the right toes grip the cepala (cone-shaped wooden hammer) which the dalang strikes against the puppet chest both to cue the musicians and provide sound effects.

The third goal of traditional wayang deals with creative innovation which has sustained wayang for a thousand years. While the traditional convention is often very rigid, there is always room for the dalang’s own skill, known as kawi dalang (literally, “creativity of the puppet master,” see Sedana 2002). The dalang’s personal interventions and improvisations include his/her insights in plot interpretation, presentation, and spiritual messaging. For example, a dalang in a performance may need to recall the names of the nine Gods of the eight directional points and the center, and then activate for each their specific attributes (Figure 2). For example, in the case of Brahma, God of Fire, he is associated with technological innovation, and the south. The puppeteer must represent this deity with skill during the presentation, as he/she activates: 1) narration describing character and place; 2) comedy and puns; 3) musical accompaniment; 4) puppet movement and manipulation; 5) dramatic content and objectives (entertainment, social commentary, and enlightenment), and improvised or quoted poetry; 6) choice of figures to appear; 7) scenic design; 8) improvised response to any expected or unexpected situation; and 9) taksu (a charismatic power associated with spiritual force)—all these nine features must be specifically appropriate to the fiery Brahma when he is the God concerned. The puppeteer must have the same facility for each of the nine Gods).[4]

In the teaching we give at ISI (Institut Seni Indonesia) in Denpasar, we assert a dalang must be able to cover the nine categories above for each of the nine Gods, with similar mastery. This kind of encyclopedic command of wayang should extend beyond just the Gods to all of the hundreds of characters that appear in the major epics (especially the Ramayana and Mahabharata). If, for example, the dalang speaks of Yudistira, the eldest of the five Pandawa brothers in the Mahabharata, the puppeteer must remember Yudistira’s multiple names (Dharmawangsa, Samiaji, Dharmaraja, Dharmasuta, Dharmaputra, Ajatasaru, Sudarmengrat, etc.), details of his parentage (Pandu as step-father, God Dharma as father, and Lady Kunti as mother), his spouse (Drupadi), his kingdom(s) (Astina, Amarta), his heirloom treasure (Kalimasada), stories of his truthfulness, and so on. All this knowledge must be on the tip of the performer’s tongue as the actual story of the evening is improvised during the performance.

The fourth goal is to be a resourceful artist cum scholar to adopt and adapt contemporary strategies for the popularity of puppetry today. Today’s academically trained artist-scholars only began to appear from the 1960s as the first tertiary programs in puppetry/pedalangan began producing graduates. Even today, only very few puppetry artists obtain this tertiary academic degree that was unavailable when their grandparents were studying in the nonformal education mode, before the government opened the school. Today, ISI can help students expand wayang beyond their indigenous Balinese milieu, inviting them to experience radical adaptations in their aesthetic approach, narrative sources, plot construction, manipulation techniques, puppet design, and other features.

As faculty, we expose our students to experimental performance in Indonesia and internationally. At ISI they study literature, music, puppet making, and plot construction in an organized manner with top local exponents of each of these sub-areas. Many of the teachers have toured to puppetry festivals and performances across the globe and can alert the students to transnational currents. In experiencing this new formal way of training, the student artist (who often comes from a traditional dalang family) must learn to deconstruct and reposition the family/village experience. When he/she leaves ISI, he/she will understand not just a parent’s practice, but differences in styles across the island, nation, and world. For example, in North Bali’s tradition, only two gender metallophones accompany the art, which is significantly different from the southern tradition, where the Sukawati village-style dominates. Students will also have an understanding of Javanese, Sasak (Lombok island), and other wayang traditions of Indonesia. We expose our students to puppetry and mask performance styles across the globe (three-person manipulation of bunraku style, pop-up book narration style, water puppetry, etc.). When a student graduates from ISI, a dalang is ready to innovate in ways that are cosmopolitan and yet also sensitive to tradition.

Access to Wayang Education

The traditional wayang training of the past used the pendopo (open air pavilion) of an aristocratic family. Those who went to such a training center were able to further develop wayang as they moved beyond the in-family instruction in their home villages. The circle of teaching widened from just a single dalang teaching his/her own children or grandchildren to training a number of non-related apprentices. With the opening of the secondary and tertiary arts educational institutions by the 1960s, major dalang artist-practitioners were appointed as teachers.[5] Due to their exceptional artistic skill (albeit lack of formal academic degrees), the school director of that period assigned senior dalang, including Dalang I Made Sidja (1933- ), the late I Nyoman Rajeg, the late Ida Bagus Sarga, I Wayan Wija, Dalang I Wayan Nartha (1942- ), and others, as teaching staff in wayang, gamelan, dance, etc.[6]

In addition to high school art conservatories, today Indonesia has eight tertiary arts training institutes, from Padang Panjang in West Sumatra to Papua in Eastern Indonesia. However, a formal degree in puppetry (wayang) is only taught in three institutions—Institut Seni Indonesia-Yogyakarta, -Surakarta, and -Denpasar. Wayang is also included in some classes at Institut Seni Budaya Indonesia (Indonesian Institute of Arts and Culture) in Bandung and Sekolah Tinggi Kesenian Wilwatikta (Wilwatikta Arts School, STKW) in Surabaya.[7] Unlike the village training, typically led by a solo instructor, the formal school puppetry training center has more than a dozen instructors who, while often from puppetry families, have now also completed a bachelor’s degree and an MA, or more recently, a PhD in pedalangan (puppetry). Each instructor at ISI-Denpasar focuses on one or two different areas of puppetry theory and/or practice. Consequently, students obtain ample access to the wayang’s artistic content. This includes training in the narratives/literature, speech, musicianship, puppet manipulation, figure design, wayang puppet making, and socio-cultural messaging of the art (be it for entertainment, edification, or social criticism). Having passed the required courses, a personal creative final project is required for each degree. Many students are hard put to fund their final performance (which typically might cost US $1500 to $3000), which is roughly equivalent to the annual median per capita earnings on the island. Consequently, fifteen per cent of the students fail to complete their studies, but of course they can still become dalangs. Talent and not a degree makes for a successful performer.

Through imitation and emulation, the students will, with time, understand how to develop their own creative improvisation based upon, yet different from, their gurus. A successful innovation can become a tradition within a generation as it is adopted by other puppeteers. For example, wayang tantri, telling animal stories—a Balinese version of the Indian Panchatantra—is a relatively recent genre popularized by I Wayan Wija, beginning in 1982, and is based on the use of the tales in an ISI project in 1980 (see Cohen 2007). Wija’s many jointed animal puppets and deft manipulation won over audiences throughout the island. By 1997, a series of wayang tantri performances by puppeteersfrom all areas of the island were part of the annual Bali Arts Festival competition. Other successful innovations also include wayang Babad (1988) by Gusti Ngurah Serama Semadi and Wayang Arja opera innovation (1988) by I Nyoman Sedana, which, after being successfully presented on campus to complete a degree, spread smoothly out to all eight regions through festival competitions held by the office of Bali Cultural Division.

Such innovative works with new stories or puppetry techniques, often done by more than one puppeteer with a non-conventional music orchestra, make up wayang kontemporer. By changing, the tradition develops new audiences, survives, and thrives. When a show takes place in a large open stage such as Ardha Candra (Bali Arts Centre), a city square, or on the beach, it can attract up to 5000 viewers. Such mass audiences are attracted to the expertise of the previously mentioned Dalang I Wayan Nardayana’s (a.k.a. Dalang Cenk Blonk). His performances display facility in speech, story, song, social commentary, and jokes (see Jenkins 2010, Foley 2012, and Hendro and Marajaya 2023). Political parties and government agencies sponsor his performances, paying his high fee. Officials see him as helpful in gathering support for their programs and helping them win elections. Other noted figures, in addition to Dalang I Wayan Wija (discussed above in relation to wayang tantri), include Dalang Joblar (I Ketut Muada), best known for his humor.

The Motives and Goals of Contemporary Puppetry

All students at the Indonesian art institutions are challenged to produce their final projects, be it to present a traditional, innovative, or contemporary work. In our pedalangan program, by taking the komposisi pewayangan (puppetry composition) class the year before their presentation, students explore and develop all aspects of the project. The student will work on concept and budget with his/her professor to strengthen the written project proposal. The plan includes the background, imaginative idea, media, objectives, sources, performance technique, plot/script, and story board. If the application is approved, the student will then use his/her story board and rehearse from one to three months. under the assigned advisers. Both the puppert production and the performance script develop side by side. However, the comprehensive examination with several judges is always held after the public performance, during with the judges witness the public reactions over the show.

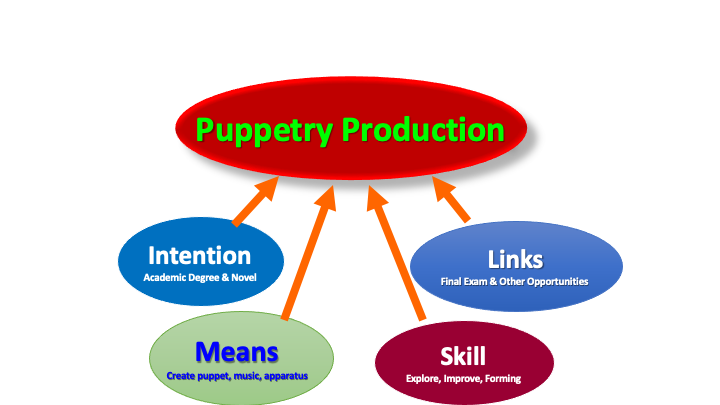

Contemporary puppet productions done by students at ISI require what we at ISI specify as the strengths associated with Wisnu (the preserver God): 1) intention, 2) means, 3) skill, and 4) links (Figure 3). As visualized in the following chart, the intention of most of my students is both to get their academic degree and create something novel in their culminating production.

The “intention” comes with the student’s original proposal, which they clear with teachers, assigned as advisers, who will judge the outcomes along with the external examiners. The “means” include producing new puppets of innovative characters—often bigger in size so the figures can be better seen from a distance, along with the supporting multimedia. Recent examples include a large pop-up book to tell a tale critiquing out-of-control land development in Bali, 1.5-meter leather puppets that are danced as well as manipulated, and other innovations. Such figures require students to learn new manipulating techniques. For these new works, students often compose new music with a hybrid ensemble made up of the existing Balinese and imported instruments—drum kits, guitars, and Javanese percussive instruments are often added. Students create new stage apparatus using LED lights, or mirrors on which they paint images that can look like ghostly apparitions when the reflection is cast on the shadow screen. “Skill” is developed as the candidate rehearses, revises, and sets the work. The “links” come as the student tries to build connections between the thesis production and other performance opportunities. The work will fulfill the requirements for their final exam for secondary and tertiary education, but the best work will ideally go beyond, to present, for example, at Bali’s annual arts festival held each June-July or at other venues. Some of these projects were also presented at the 2023 puppet festival during the UNIMA International Council meeting in Denpasar, Bali.

As a government sponsored art institution, ISI requires pedalangan students to present forty-five-minute to one-hour presentations of wayang to complete their degree studies. And most choose to do wayang kontemporer. The videos and the performance scripts are thereafter archived in the campus library and Bali Pusyandis (Pusat Layanan Data dan Informasi Seni Budaya, Office of Data and Information on Culture and Arts). The course requirements for a BA are less stringent, but more of course is expected for an MA. For a successful PhD, candidates in puppetry must pass rigorous training, including a class in philosophy/religion/aesthetics (linggayoni tatwa widya lango).

Sample abstracts of successful final projects in recent years are listed at https://repo.isi-dps.ac.id/view/divisions/puppetry/ (in Indonesian language, accessed 30 June 2023). One strong presentation was Budi Setiawan’s2014 Mouse Mahabharata (Musaka Bharata), a forty-minute piece that translated the characters of the Indian epic into mice and rats. The play did not trivialize the tale but, using shadow and rod puppets, made viewers rethink the narrative via the transposition of heroes into animals. (See http://repo.isi-dps.ac.id/1967/, accessed 25 Aug. 2023).

I Made Sudarma’s The Tale of Ganesa (Pakeliran Darta Ya Purna Ganesa 2013, see http://repo.isi-dps.ac.id/1916/). The title’s “dar” was for d[a]rama, “ta” for tari (dance) and “ya” for wayang (puppetry), as the work combined all three. The story was not drawn from regular Balinese narratives but told the Indian purana tale of Ganesa (India’s Ganesha), the important elephant-headed son of God Siwa (India’s Shiva). The elephant God is important historically in Indian iconography, but the tale of how he became the guardian of openings/doorways and how he got an elephant head is not normally performed in the Balinese tradition. Due to the contemporary Hindu revival that has exposed our students to Indian purana stories, Made Sudarma was attracted to this narrative. The show presented how Siwa (Ganesa’s father who had yet to meet him) came home and found Ganesa guarding the door as his mother, Uma, bathed. Not recognizing the boy as his son, the jealous Siwa tore off Ganesa’s head, but restored the boy to life with the head of a passing elephant when alerted he had murdered his own child. Dancers represented the divine family (Siwa, Uma, and child Ganesa). They moved in Balinese dance idiom in front of and behind a shadow screen. Scenes with normal wayang parwa figures of the divine characters alternated with such dance episodes. Extensive lighting effects with gorgeous colors painted the proscenium stage. Issues of inter-family violence, of course, were infused into the interpretation.

This and other pieces have been excellent examples of wayang kontemporer. However, such works often have limited opportunity to be performed in temple ceremonies (a normal venue in Bali for successful dance presentations), due to the lack of ritual and purification functions inherent in these tales. Such new stories are not required in the ceremonial context in the way traditional wayang parwa is. What is more, a piece like The Tale of Ganesa required many performers (nine dancers, five puppeteers, fourteen musicians, three lighting crew, two singers, and various other helpers). Getting a troupe of thirty to tour is much more complicated than the regular four gender plus one dalang and a puppet passer of wayang parwa. Thus, these graduation performances are secular creative exercises that are rarely folded back into wayang as a ritual form. However, such performances clearly reflect the enthusiasm of the student as planned in consultation with faculty members who judge the success.

An extreme example of the visual and technical changes students attempt is Wayang Renung Temu Semara (Wayang Ruminating on the Theme of Love), I Made Georgiana Triwinadi’s thesis production of 2020. It included actors, newly made giant puppets (about three-quarters human size), pre-recorded contemporary music, and required two dozen puppeteers (see Georgiana 2020 at https://drive.google.com/file/d/16HJcfUHl7v9r48bm4QjOUJ7rfUdQvOmY/view, accessed 23 July 2023). The narrative combined Georgiana’s troubled relationship with a girlfriend (presented in a realistic acting scene), which was paralleled with the Ramayana tale of demon king Rahwana kidnapping Princess Sita. These epic characters were represented by large leather puppet figures based on the normally small wayang parwa models. Each figure was manipulated by a single puppeteer (in normal performance one dalang would present all). The scene of young lovers arguing amidst a forest of giant kayons (tree of life puppets, see Georgiana 2020: 1:46-2:40 at https://drive.google.com/file/d/16HJcfUHl7v9r48bm4QjOUJ7rfUdQvOmY/view, accessed 30 June 2023) was followed by Rahwana seizing Sita (2:47-3:03). The performance interrogated dysfunctional male-female relationships. An example of the dialogue is Georgiana addressing his girlfriend and saying,

You won’t ever be my Sita, and I won’t be your Rama, because . . . Rama and Sita are only our example. Rama is a symbol of struggle while Sita is a symbol of feeling. If the struggle meets the feeling then love will occur. But the struggle is often prevented by the ego, and Rahwana is symbol of ego. (Georgiana 2020)

This infusion of realistic and semi-autobiographical material interwoven in a performance is relatively new. It responds to young people’s thirst for making more proximate their identification with the old stories and characters. The personal drama served as a “bridge” to the epic drama of Sita’s kidnapping from times past. The rough language between the angry couple would never find its way directly into traditional wayang parwa. It could only be filtered through the translation of the clowns or only be presented with the stylization of Kawi (the Sankritized language of puppetry, not understood by the average viewer). Linguistic complexity would provide distance in a classical wayang parwa. This use of actors in front of the puppet space meant the performance felt “real” and was presented in a style that almost seemed like method acting with its use of emotional memory as a tool of actors getting into character. This realistic style represents a relatively new, middle class, urban theatre which, in this show, was layered on top of traditional epic narrative and puppet stylization.

In another ISI project, student I Putu Agus Meliartawan (2021) developed dozens of almost human-sized, three-dimensional wayang figures from dry banana tree trunks, a form he called wayang debong (banana trunk wayang, see https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xT9NhkvioEs, accessed 30 June 2023, for a sample).[8] A grandfather (played by an actor) served as narrator, telling the tale to his grandson (a child actor). Puppets were large rod puppets with the lead puppeteer holding the central rod (trunk and head), with the lead puppeteer’s lower body giving the impression of feet (as the manipulator moved in Balinese dance style). A second manipulator (directly behind the first) operated the two hand rods and moved in dance steps of the character type of the wayang figure along with the lead manipulator. Lakuning Sato (Conduct of the Beasts) was a story drawn from the Tantri cycle, the Balinese version of the Indian Panchatantra animal stories (discussed above in Dalang I Wayan Wija’s more conventional wayang tantri style).

In the tale, Shri Adnya Dharmaswami, a priest, is wandering in the forest after freeing creatures (monkey, snake, tiger) caught in a well. He is later assisted by these grateful animals when humans—the courtier Swarnangkara and his misguided monarch—act like beasts, persecuting the old man. The animals defeat Swarnangkara and, finally, the King realizes the false counsel of Swarnangkara has led him to attack the sage. The performance was outdoors in front of Temple Pemerajan Agung, Banjar Taman, Intaran, in Sanur because COVID-19 restrictions prevented indoor presentation. This production was innovative in story, manipulation technique, and it explored a new style of puppetry—large three-dimensional rod puppets.

All graduation projects are performed before the public, ISI faculty, and external examiners. The music, puppet manipulation, story, and number of performers in these ISI-Denpasar degree projects is often impressive and experimental. These works contrast significantly with the more traditional shadow puppet shows a student might present for their high school graduation production in the puppetry department at Sekolah Menengah Karawitan Negeri 3 (National High School of the Arts Conservatory, see https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eoUWVi3zg0Y, accessed 23 Aug. 2023). High school productions tend toward following tradition while ISI graduation projects tend toward large-scale pieces based upon stories that are not conventionally presented in wayang with multimedia and avant-garde tendencies.

Conclusion

Training in Balinese wayang can of course be done in the older, village style. But for many would-be dalangs, who are often children of a dalang, ISI provides a path to meld tradition and modernity. Higher education is valued. In classes and thesis productions, emerging artists plumb the tradition and interrogate what they have learned by watching parents perform. They widen their vision to encompass wayang in other areas of Bali and Indonesia, borrowing aspects. They find how wayang fits into a wider world of puppetry, creating pop-up books, giant leather puppets, and bunraku-style figures. They cross the borders of their art, melding dance, realistic theatre, new designs, lighting, etc. They must learn to write about their work (for their theses) as well as performing their creation. They emerge with visions of the many possibilities that can take this important heritage art into the future.

[1] On wayang kontemporer see Gold (2013), Stepputat (2013), and Sedana (2005). On religious applications see Hooykaas (1973), Hobart (2003), Keeler (1992), Stephen (2002), and Zurbuchen (1987).

[2] In 2008 the Masterpiece program was transitioned into the simpler Representative list of Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity designation. For material on wayang see https://ich.unesco.org/en/RL/wayang-puppet-theatre-00063, accessed 24 July 2023.

[3] See for example Hooykaas (1973) for the variety of mantra used by puppet masters. Other discussion is found in Hobart (2003), Keeler (1992), Stephen (2002), and, Suweta (2019). The article by Wicaksana, Purnamawati, and Wicaksandita(2023) in this issue of Puppetry International Research 1, No. 1 is an example of a story which is required for those needing a spiritual purification through watching a performance.

[4] The image is a teaching diagram used in my ISI classes. I hope in a future paper to give a full explanation of all the details.

[5] The high school of performing arts was originally called Konservatori Karawitan (KOKAR, Conservatory of Traditional Music/Performing Arts), but is now Sekolah Menengah Karawitan Indonesia (SMKI, High School of Traditional Music/Performing Arts). The tertiary-level School was called ASTI (Akademi Seni Tari Indonesia), but is now ISI. My article, “The Education of a Balinese Dalang,” goes into greater depth on village and school-based education of wayang from a student perspective circa the 1990s (Sedana 1993).

[6] Interestingly, the dalang offspring of each of these traditionally trained masters have since graduated from the ISI training programs and currently serve as teachers in the disciplines their fathers taught in the early years, showing that a combination of formal and informal education persists. I Made Sidia is the son of Dalang I Made Sidja and I Ketut Sudiana is the son of Dalang I Wayan Nartha.

[7] Some of the graduates of these puppet programs, such as myself, are able to continue their education abroad for an MA or PhD.

[8] See also Meliartawan and Sudarta (2021).

References

Artaud, Antonin. 1976. “On the Balinese Theater.” Salmagundi, No. 33/34: 103-114. http://www.jstor.org/stable/40546926, accessed 13 May 2023 [also in Artaud, Antonin. 1958. The Theatre and Its Double, trans. by Mary Caroline Richards, 53-67. New York: Grove Wiedenfeld].

Cohen, Matthew Isaac. 2007. “Contemporary Wayang in Global Contexts.” Asian Theatre Journal 24, No. 2: 338-69. http://www.jstor.org/stable/27568418, accessed 13 May 2023.

Foley, Kathy. 2012. “Cenk Blonk.” World Encyclopedia of Puppetry Arts. https://wepa.unima.org/en/cenk-blonk/, accessed 13 May 2023.

Georgiana, I Made. 2023. Wayang Renung Temu Semara (Wayang Ruminating on Love). https://drive.google.com/file/d/16HJcfUHl7v9r48bm4QjOUJ7rfUdQvOmY/view, accessed 30 June 2023.

Gold, Lisa, 2013. “Time and Place Conflated: Zaman dulu (a Bygone Era) and an Ecological Approach to Traditional Balinese Performing Arts.” In Performing Arts in Postmodern Bali. Changing Interpretations, Founding Traditions, ed. by Kendra Stepputat, 79-108, Aachen: Shaker Verlag [Grazer Studies of Ethnomusicology].

Hendro, Dru, and I Made Marajaya. 2023. “Cenk Blonk’s Balinese Shadow Puppetry During the Covid Pandemic.” Puppetry International Research 1, No. 1.

Hobart, Angela. 2003. Healing Performances of Bali. New York: Berghahn Books.

Hooykaas, C. 1973. Kama and Kala: Materials for the Study of Shadow Theatre in Bali. Amsterdam, London: North Holland Publishing Company.

Institut Seni Indonesia Denpasar. n.d. Institutional Repository. https://repo.isi-dps.ac.id/view/divisions/puppetry/, accessed 30 June 2023.

Jenkins, Ron. 2010. Rua Bineda: Counterfeit Justice in the Trial of I Nyoman Gunarsa. Yogjakarta: Institut Seni Indonesia.

Keeler, Ward. 1992. “Release from Kala’s Grip: Ritual Uses of Shadow Plays in Java and Bali.” Indonesia No. 54: 1-25. https://www.jstor.org/stable/3351163, accessed 14 April 2023.

Meli[artawan], [Putu] Agus. 2021. Wayang Gedebong “LAKUNING SATO” – Ujian TA Seni Pedalangan 2021 (Agus Meli) (Banana Trunk Wayang, Conduct ofthe Beasts Art Exam in Puppetry 2021 [Agus Meli]). Aug. 15. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xT9NhkvioEs, accessed 30 June 2023.

Meliartawan, I Putu Agus, and I Gusti Putu Sudarta. 2021. “Garapan Inovatif ‘Wayang Debong Lakuning Sato’” (Innovative Performance “Wayang Debong Conduct of the Beasts”). ISI Journal 1, No. 1. https://jurnal2.isi-dps.ac.id/index.php/damar/issue/view/25, accessed 27 Aug. 2023.

Rubin, Leon, and I Nyoman Sedana. 2007. Performance in Bali. NY: Routledge.

Sedana, I Nyoman. 1993. “The Education of a Balinese Dalang.” Asian Theatre Journal 10, No. 1: 81-100. https://doi.org/10.2307/1124218, accessed 30 June 2023.

_____. 2002. Kawi Dalang: Creativity in Wayang Theatre. PhD, University of Georgia. https://www.academia.edu/77909601/Kawi_Dalang_Creativity_in_Wayang_Theatre, accessed 13 May 2023.

Sedana, I Nyoman. 2005. “Theatre in a Time of Terrorism: Renewing Natural Harmony after the Bali Bombing via Wayang kontemporer.” Asian Theatre Journal 22, No. 1: 73-86. doi:10.1353/atj.2005.0012, accessed 27 Aug. 2023.

Stephen, Michele. 2002. “Returning to Original Form: A Central Dynamic in Balinese Ritual.” Bijdragen Tot de Taal-, Land- En Volkenkunde 158, No. 1: 61-94. http://www.jstor.org/stable/27865814. accessed 7 July 2023.

Stepputat, Kendra. 2013. “Using Different Keys, Dalang I Made Sidia’s Contemporary Approach to Traditional Performing Arts.” In Performing Arts in Postmodern Bali. Changing Interpretations, Founding Traditions, ed. by Kendra Stepputat. Aachen: Shaker [Grazer Studies of Ethnomusicology].

Sudarma, I Made. 2013. Pakeliran Darta Ya Purna Ganesa (Drama-Dance-Wayang Performance The Tale of Ganesa) http://repo.isi-dps.ac.id/1916/, accessed 27 Aug. 2023.

Setiawan, I Kadek Budi. 2014. Musaka Bharata (Mouse Mahabharata) http://repo.isi-dps.ac.id/1967/, accessed 25 Aug. 2023.

Suweta, I Made. 2019. “Teks Lontar Kala Purana (Kajian Filosofis, Simbolis, dan Nilai)” (The Text of the Palm Leaf Manuscript Kala Purana [Studies of Philosophy, Symbolism, and Values]). Genta Hredaya 3, No. 1. https://stahnmpukuturan.ac.id/jurnal/index.php/genta/article/view/444, accessed 7 July 2020.

UNESCO n.d. “Wayang Puppet Theatre.” https://ich.unesco.org/en/RL/wayang-puppet-theatre-00063, accessed 24 July 2023.

Wicaksana, I Dewa Ketut, Ni Diah Purnamawati, and I Dewa Ketut Wicaksandita 2023. “Bhatara Kala: Sacred Myth in Balinese Wayang Parwa Shadow Puppetry.” Puppetry International Research 1, No. 1.

Zoetmulder, P. J. 1974. Kalangwan: A Survey of Old Javanese Literature. The Hague: Martinus Nijhof.

Zurbuchen, Mary. 1987. The Language of Balinese Shadow Theater. Princeton: Princeton Univ. Press.