Early European Puppetry Studies Conference. Yale University, Connecticut. October 13-14, 2023.

The article summarizes the offerings at the two days of presentations at the Early European Puppetry Studies conference organized by Michelle Oing and Nicole Sheriko at Yale University in October of 2023. Participants from a wide range of disciplines, including Medieval Studies, Art History, and English, investigated how using puppetry studies as a lens could help shed new light on a variety of performative events from early Europe. In so doing, the event demonstrated the promise this research area holds as a new field of study.

Claudia Orenstein, Theatre Professor at Hunter College and the Graduate Center, CUNY, has spent nearly two decades writing on contemporary and traditional puppetry in the US and Asia. Recent publications include Reading the Puppet Stage: Reflections on Dramaturgy and Performing Objects(UNIMA-USA Nancy Staub Award, 2024) and the co-edited collection Puppet and Spirit: Ritual Religion and Performing Objects (in two volumes).

The Early European Puppetry Studies conference, organized by Michelle Oing, Lecturer in the Department of Art and Art History at Stanford University, and Nicole Sheriko, Assistant Professor of English at Yale University, offered a rare opportunity for scholars across fields to engage in cross-disciplinary discussion about puppets and related figures in Europe from the late Middle Ages through the early Renaissance. Oing and Sheriko intentionally invited researchers from Medieval Studies, Art History, and English, some of whom had never previously thought about their work within the context of puppetry, to consider their research through this lens. The two days of papers and presentations revealed the presence of performing objects in churches, court entertainments, public plazas, and private homes throughout the period and offered a rich variety of critical approaches to this diverse material. Oing and Sheriko thoughtfully planned for the event to include ample time for discussion after each panel and at the end of the conference, all part of their goal of galvanizing further exchange in and development of this corner of scholarship. The conference also provided plenty of opportunities for informal conversations at communal meals organized for the presenters. Several prominent puppetry scholars, who were not presenting, also attended, eager to engage with this expanding area of research and contributed their views and expertise during discussion sessions.

Oing and Sheriko kicked things off by explaining their overall intentions for the weekend and each offered a quick overview of her own research. Oing shared how puppetry has been a guiding idea for her investigations of jointed medieval Christ figures, as described in several published articles and within her book project, “Puppet Potential: Religious Sculpture and the Aesthetics of Play.” A puppetry perspective, she said, helps crumble binaries and creates a space of play. Sheriko discussed her interest in what puppetry can reveal both about bodies at play and early modern theatre. She has been pursuing these questions within her book project, “Lively Things: Puppet Performance and Renaissance English Theater.”Oing and Sheriko underlined how the ephemeral nature of this field complicates locating concrete evidence. Seeking to address this issue through collaboration among scholars, they have added a resource-sharing page to the conference website for participants to contribute to: https://www.earlyeuropeanpuppetrystudies.com/resources

Marking a life cycle trajectory, the first day began with the panel “Puppetry and Children,” and it ended with “Puppet Death and Violence.” On the first panel, with “Artificial Life in English Civic Pageantry,” Scott Trudell, from University of Maryland, showed that in the Renaissance, before the sentimentalization of childhood, children were commonly associated with non-human bodies and an interest in puppet-like figures overlapped with a fantastical view of children’s miniature stature. He revealed how children often appeared alongside crafted mythic or allegorical figures on decorative structures in large outdoor celebratory events contributing to ambiguities about which figures were animate. In court-sponsored performances, which were politically charged, children might symbolically evoke an ongoing political future such as a king’s promise of future succession. Some pageants surprisingly included as many as 200 children. Trudell’s paper was followed by “Bypassing the Interpreter: Child Actors, Ben Jonson’s Epicene, and the Power of Puppets,” from Isabel Dollar of St Andrews University, Scotland. Dollar argued that Ben Jonson, in his early dramas, commonly links the puppet metaphorically with the powerless or voiceless, and places actors in opposition to authors. However, these associations shift in his later plays. After years of working with children’s companies, so prominent in the period, Jonson saw the child actors grow up and move on to professional careers. Nathan Field, for example, became a fellow playwright. Analyzing Epicene and Bartholomew Fair, Dollar argued that, in Jonson’s later plays, performers are portrayed more as blank slates with prosthetic elements projecting their social and public character, making them more akin to objects.

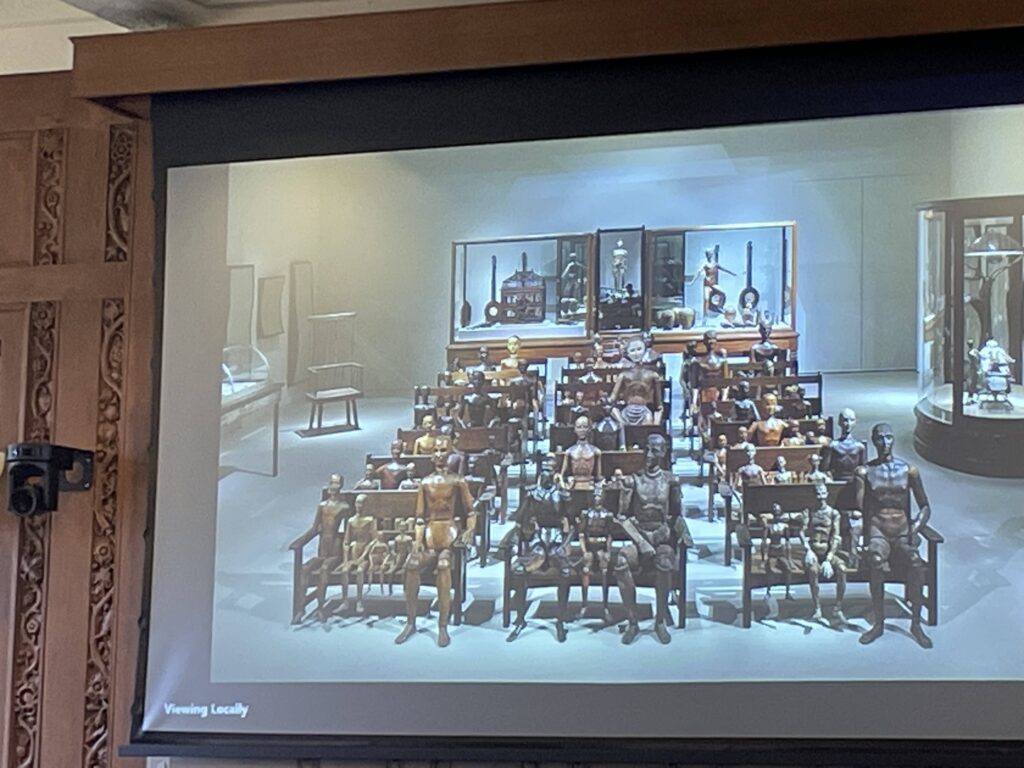

The next panel, “Puppetry and Dolls,” began with “On the gender of the jointed doll,” from Markus Rath, from Universität Trier in Germany, investigating both the presentation and absence of genitalia in jointed figures from antiquity through the Renaissance and the cultural meanings these choices express. In ancient Greece, female dolls with breasts were associated with fertility and some three-dimensional figures even have abdominal cavities built to hold crafted fetuses. In the Roman period, female dolls, decked in jewels, represent a feminine ideal. Jointed figures in the Middle Ages, predominantly representing Christ or saints, did not have genitalia, even in cases where undressing a Christ figure was part of a performance of the Passion. Childlike manikins of Christ with small penises, however, did exist, and there are reports of nuns having erotic experiences with such figures. In the fifteenth century, jointed figures were primarily those used by artists for figure sketching and drapery studies, what Rath calls “intersex instruments,” with no gender-specific details. Adding on female breasts or a male tunic allows these figures to take on gender identification as needed. In the sixteenth century, jointed figures found within cabinets of curiosities were fully sculpted bodies, with genitalia included, and were artworks themselves as well as tools for artists.

Michelle Moseley from Virginia Tech followed with “‘Beautiful and Extraordinary!’: Intersections of Puppetry, Performing Objects, and the Early Modern Dutch Dollhouse as Staged Spectacle.” She focused on the performative aspects of dollhouses assembled by middle- class women in Leiden and Amsterdam in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. These women gave tours of their dollhouses to guests, narrating and displaying details while reaching in to move characters and offering anecdotes and stories. In effect, these private tours became performative events that echoed street performances of the day, including the rarekiek kast peep boxes carried by itinerant performers and the kijk kast where performers revealed scenes within boxes.

On the panel “Articulated Christ Sculptures as Puppetry,” Una D’Elia, from Queen’s University, Canada, offered “The Dead Weight of Christ and the Mechanics of Performance.” She used contemporary performance practices, period documents, and artworks, along with practical consideration of the physics of bodies and objects, to determine how jointed figures of Christ were brought down from their crosses during medieval Church performances of the Passion. In such acts, practical and poetic solutions must have merged to pull off gracefully what was simultaneously a significant dramatic moment and a physically awkward feat. Ariella Algaze of Johns Hopkins University followed with “Vernacular Puppetry and the Crucifix-as-Actor in Italian Confraternal Drama,” analyzing jointed Christ figures and Church performances in Italy. She underlined the counterintuitive situation that, while critical discussion of puppets and performing objects tends to center on how materiality is brought to life, in these acts, the crafted Christ figure is used conversely to show the moment of death. These medieval figures are crafted to droop, to show blood flowing, and in other ways to demonstrate lifelessness and their own “deanimation.”

The last two panels of a very packed first day were “Puppet Bodies and Materiality” and “Puppet Death and Violence.” The first included “Hidden in Plain Sight. The Cleverly Concealed Puppeteer in Wolfgang von Kempelen’s Chess Automaton,” from Manuel Schaub of Universität Konstanz, Germany, focusing on the specific strategies used to create the illusion of a working automaton in von Kempelen’s well known fraudulent eighteenth-century automaton figure. Schaub emphasized how the case of the chess-playing Turk automaton, which had a human hidden inside it making the moves, opens up discussions into the possibilities and limitations of mechanization connected to current discussions of AI. He noted how, even after the Turk’s trick was publicly revealed, many people were still committed to believing it to be a magic self-moving and thinking machine. Jodie Coates, of University of Cambridge, England, in “Moveables of the Middle Ages as Paper-Engineered Puppetry,” described a range of intriguing books from the period built with moveable parts. These included one with a map of the world that expanded to show a medieval view of planetary orbits around the earth, the thirteenth- century Book of Fate, whose extensions helped the reader take a journey to divine their future, and a sixteenth-century tome featuring human anatomy with layered biological parts that could be removed to reveal others. As with Rath’s jointed figures, the moving features of these volumes also chart shifts in European culture and thought as religious belief gave way to scientific models. The panel finished with “Wax, Skin, and Paint: Vibrant Bodies in Fifteenth-Century Performance” from Laura Weigert of Rutgers University. Weigert discussed Renaissance interludes and similar events that combined dancers, mechanical figures, and sprouting fountains to create extravagant performances. Looking at these through a puppetry lens, she said, does not reinforce the distinction between bodies and things but retains the potential for both to become activated in performance.

The concluding panel of the first day began with Durham University’s Beth Clancy’s “‘Better play then playe either at ches or tables’: Chess, Death and Puppetry in the Book of the Duchess,” with a focus on the materiality and chess imagery in Chaucer’s “Book of the Duchess.” Clancy showed how Chess parallels puppetry in evoking metaphors of power and authority. In “‘Dressed in Tiers to Bear a Part’: The Manipulation of Female Corpses in Early Modern English Tragedy,” Ayesha Verma, from Columbia University, investigated Renaissance plays, such as Thomas Middleton’s The Revenger’s Tragedy, in which characters manipulate skulls or corpses onstage. These are both reminders of the death that comes to all of us and sometimes serve as agents of death as well within the plots. In some plays, Verma noted, women’s agency in particular comes into question when a corpse is dressed up and performed in effigy, forced to play a role even after death.

The final paper of the first day was Alexa Sand’s, of Utah State University, “Dismembered Memories: Puppets, Bodies, Laughter, and Violence in the Late Middle Ages.” Sand offered an interpretation of the rare examples of the presence of puppetry in marginalia in medieval manuscripts, notably puppet booths with battle scenes taking place. According to Sand, a good deal of marginalia show images of violence, which was associated with learning. Marginalia serves as visual commentary on the main text, for example, a depiction of death and decapitation in a puppet show on the margins of an epic tale works to diminish the heroic episode written in the manuscript.

The second and last day of the conference included four panels and finished with a Roundtable for group discussion. The first two panels focused on “Records and Reconstructing Puppetry,” which highlighted both the travails and possibilities of doing research on an ephemeral art. Alissa Mello of University of Exeter, UK, kicked off the first panel with “Charlotte Charke, Mother of Punch,” showcasing research that is part of her larger project investigating the role of women within the Punch tradition, both on and offstage. She shed light on Charke’s important place in puppetry history, arguing against the legacy of male scholars who have discounted or vilified her. Through a detailed reading of the few materials that reflect on Charke’s work and career, Mello recast the socially and politically transgressive figure as an innovator and pioneer. With “By George! How to Perform a Dragon,” Tracy Davis, of Northwestern University, used visual and textual evidence from the period to reconstruct how the dragons from the popular enactments of the story of St. George and the Dragon were constructed and manipulated. She finds clues to performance techniques within both likely and unlikely sources, and adopting a careful, performance-centered reading model, reveals how object performance questions are researchable in spite of the absence of the objects themselves. The second panel in the series began with Leanne Groeneveld, from University of Regina, and “‘then and ther a handlinge’: The case of William Appowell, Puppet Spectator and Player.” Groeneveld analyzed documentation related to one William Appowell accused of conduct unbecoming a priest at an event where a hand puppet show was presented. The priest was accused of putting his hand up a woman’s skirt and handling her in a manner comparable to the performers’ manipulation of their puppets. The accused had apparently been involved in other inappropriate behavior, notably manipulating his parishioners to sue each other. Such documents disclose the presence of puppets and the metaphorical use of the art in contexts not directly related to performance. Richard Preiss, of University of Utah, offered “Ventriloquizing Early English Puppet Theater,” and compared tropes of puppetry in English Drama that vilify puppeteers and accuse them of stealing material from the human stage to the realities in which puppetry’s fare and clientele were quite distinct from that of the theatre. Analyzing plays from the period, he showed that how the theatre thought and talked about puppetry reflected its own anxieties rather than truths about puppetry.

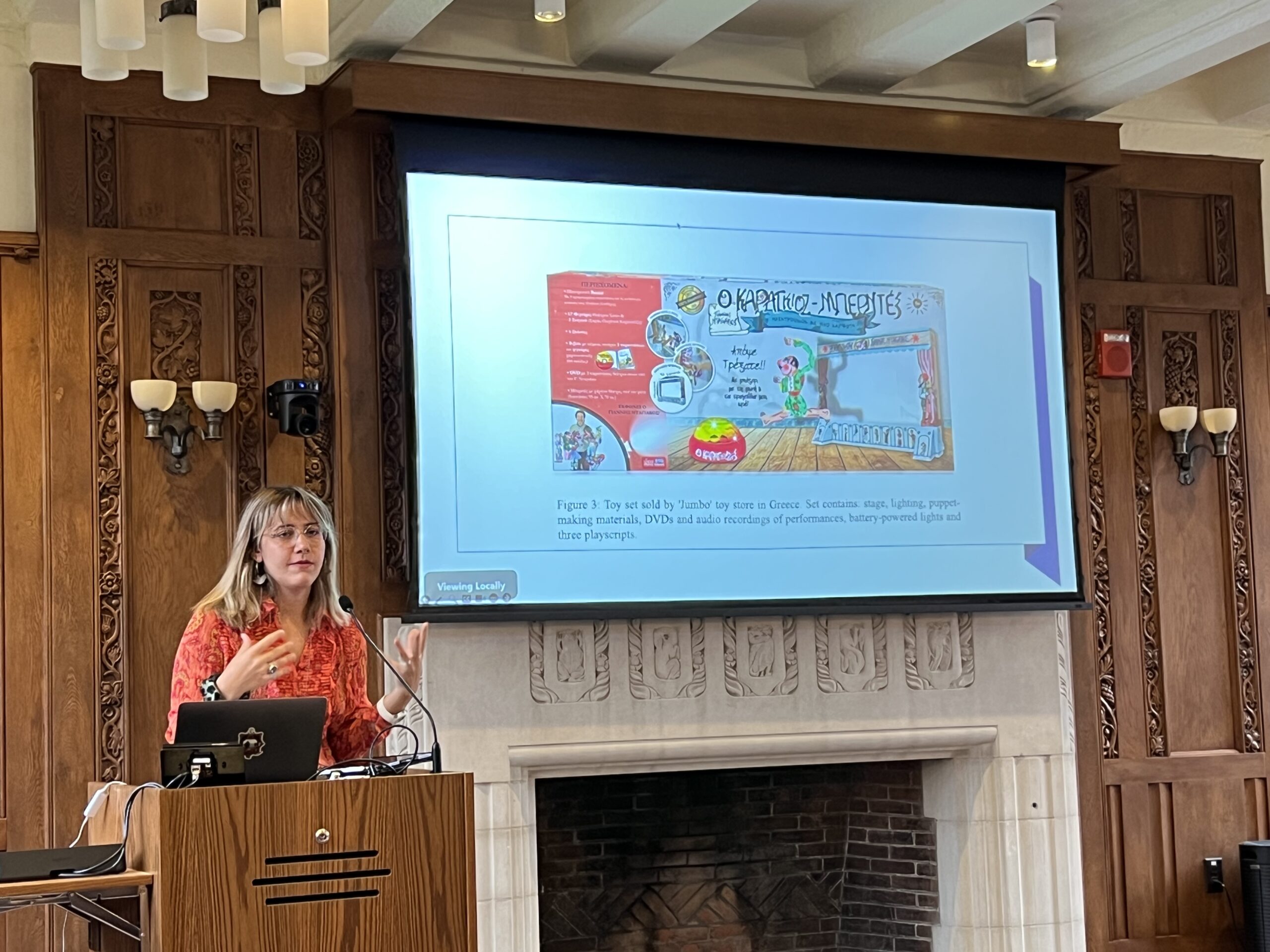

The panel that followed was “Puppetry in the Mediterranean” with Clio Takas, of Harvard University, “Disjointed Articulations: Shadow Players from Ibn Dāniyāl to Spatharis” and Christopher Swift from New York City College of Technology (City Tech), CUNY on “New Directions for Research on Puppetry in Al-Andalus.” Takas argued that the grotesque features of shadow puppets in the Ottoman Karagöz form and related traditions throughout the region served as an extension of the body of the invisible puppeteer creating, in collaboration with audiences, a carnivalesque performance. Features such as extra limbs, two buttocks, jointed phalluses, and other jointed elements of the shadow figures physically express inversion of character and play with bodies just as the shows, with their bawdy rhetoric, word play, and comic plots, invert social hierarchies and highlight outlier figures and other elements outside dominant social structures. Swift analyzed the visual imagery found in the texts of Islamic tales which may not be literal representations of shadow puppet shows, but echo shadow performances and reflect many of their scenes. In suggesting the performances, these images allow readers to animate them in their own way.

The final panel was “Puppetry and Transgression.” “Puppetry in a Medieval Iberian Performance Hierarchy,” from Patrick Kozey of Austin College went somewhat far afield in its investigation of puppetry by conceptualizing the songs of troubadours as puppets with their own kind of agency. It did so by first placing troubadours within a particular milieu of entertainers that included puppeteers, illuminating many aspects of the troubadour’s performance tradition in the process. Troubadours were welcomed at court when puppeteers were not. Northwestern University’s Phoenix Gonzalez’s “The Catalonian Caganer: Making and Managing Waste in Late Medieval Performance” discussed the popular Catalonian figure of a peasant, with pants down, crouching and pooping that is commonly, if incongruously, placed within nativity scenes in Catalonia. It has served as a symbolic celebration of Catalonian independence in political contexts. Gonzalez offered an “ecocritical” reading of the figure as a representation of rural lifestyles, through its closeness to bodily functions and the land, set against its contemporary presence in urban and commercial contexts. The final presentation was from John Bell, from the University of Connecticut and the Ballard Institute and Museum of Puppetry, with “Puppets and Passion Plays: Bread and Puppet Theater’s 21st-Century Cycle Dramas.” Bell discussed the many medieval dramaturgical models that Peter Schumann has drawn on for Bread and Puppet Theater’s performance over its long history. For example, during protest against the war in Vietnam, Bread and Puppet’s The Cry of the People for Meat included scenes based on Old and New Testament stories where Herod’s slaughter of the innocents was presented as simultaneously ancient and contemporary. In 14 Stations of the Cross, from the same period, the crucifixion was presented as an airplane with a Christ figure tied across its wings. While Schumann draws heavily from such Christian tropes, in Bread and Puppet’s work activism replaces religious belief.

The conference ended with a Roundtable discussion amongst all participants, moderated by Nicole Sheriko and Michelle Oing. Topics for discussion included reflections on the significance of the materiality of objects within research; the relationships between puppetry as practice and metaphor; what is learned by looking at puppets within various disciplines; the roles puppets play in knowledge formation; and whether and how contemporary puppetry can shed light on historical research.

The two days of events revealed that the disciplines of English Literature, Art History, Medieval Studies, on the one hand, and puppetry studies, on the other, have a great deal to offer each other in their shared interests in performative materiality and the varied critical approaches they bring to examining and understanding it. Oing and Sheriko anticipate a book project coming out of the conference, which will not only bring the depth of work from this small gathering to a wider audience but will surely establish Early European Puppetry Studies as a recognized, demarcated sphere of research.

Claudia Orenstein

Hunter College and the Graduate Center, CUNY