This short reflection explores the theme of the Jewish Holocaust in puppet theatre. The puppet theatre in Odesa recently (2023) has presented the Jewish Holocaust and this article looks at a recent production, titled Kaddish Memorial Prayer, performed in Odesa during the war in Ukraine in 2023. This article looks at the appearance of this performance as an unusual choice because of the trauma in the narrative in a production within the context of a war zone. Considering the events of the Holocaust in the midst of the Russian invasion of Ukraine could seem emotionally inappropriate given the people attending these performances are themselves enduring exceptional suffering. Even so, the Odesa Regional Puppet Theatre produced Kaddish Memorial Prayer to speak to the collective experience of its audience surviving wartime violence.

Theatre scholar Ariel Roitman confirms that the issues of puppetry portraying the Holocaust are pronounced because of the artificial nature of puppet figures (2022). They are a part of what Vivian Patraka calls the “Holocaust Performative,” and the shifting ontological issues puppetry creates, because of its oscillation of signs and meanings, are not resolved in live performance (Roitman 2022, 18). The performance of Kaddish Memorial Prayer, discussed here, does not simply resolve the trauma that it relates in its narrative, and the use of puppets complicates this tension. This unusual narrative choice for the program of a puppet theatre in a war zone opens up a painful space of absence. This relates to unresolved collective and individual traumas framed by the collective trauma of adult audiences in Odesa who see this production within the very real presence of the violence that is contextualizing them. This is further complicated by the historical narratives which are affected by current concerns about confronting the history of the Jewish Holocaust. Roitman, though aware of the uncertainty that puppets create, still sees a possibility for this form: “Employing puppets as performers in theatre about the Holocaust serves multiple diverging inquiries about the event itself, that of spectatorship and agency, remembrance and transmission of testimony, and their therapeutic capacity” (Roitman 2022, 4). These issues and uncertainties frame the discussion of the production of Kaddish Memorial Prayerat the Odesa Regional Puppet Theatre.

Puppet theatre productions that focus on the ravages of war can offer an opportunity to work with traumatic memories, improve resilience, and help with healing. They can also be used as weapons of propaganda, leading to misrepresentations of identities. As a rule, the tragedy of the Holocaust was not often a subject for performance in the context of the Russian puppet theatre. The Diary of Anne Frank was actively replaced by The Diary of Tanya Savicheva, who died of hunger during the blockade of Leningrad in Russia. A Russian play, Call Nina, also sought to represent the trauma of Leningrad. The main character accidentally makes a telephone call to an apartment in besieged Leningrad in the 1940s, in which the Russian girl, Nina, is close to death from starvation and tries to support her over the phone. In this production, the trauma of war is located within Russian narratives, shifting the focus away from the Jewish Holocaust.

In Russia, puppetry performances exploring the Holocaust as a tragedy had to justify themselves. Kaddish Memorial Prayer is unique in having first had a Russian production, later adapted by the same director in a Ukrainian version. While the play contains no spoken dialogue, Jewish religious music is used as background music to support the theme. This includes the reciting of the Kaddish as a memorial prayer for the deceased. The Kaddish is the ancient Jewish prayer regularly recited in the synagogue service, including thanksgiving and praise and concluding with a prayer for universal peace; also, a form of the Kaddish is recited for the dead, to show that despite the loss, they still praise God. It has a wide cultural significance (McLoughlin, 2006 4).

The main character in Kaddish Memorial Prayer is a young woman named Esther, represented by an actress and not by a puppet. Spectators witness her childhood framed as part of Jewish culture: there is a lullaby in Yiddish about certain kind animals that come to lull the girl to sleep. Later, she is exiled from her home and is “marked” with a yellow Jewish star. But this is just the beginning of her suffering. Esther, along with other victims of the Holocaust who were forcibly deported from their homes, is taken to Auschwitz, where she tries to take care of a child, who eventually dies, like most of her friends in the concentration camp.

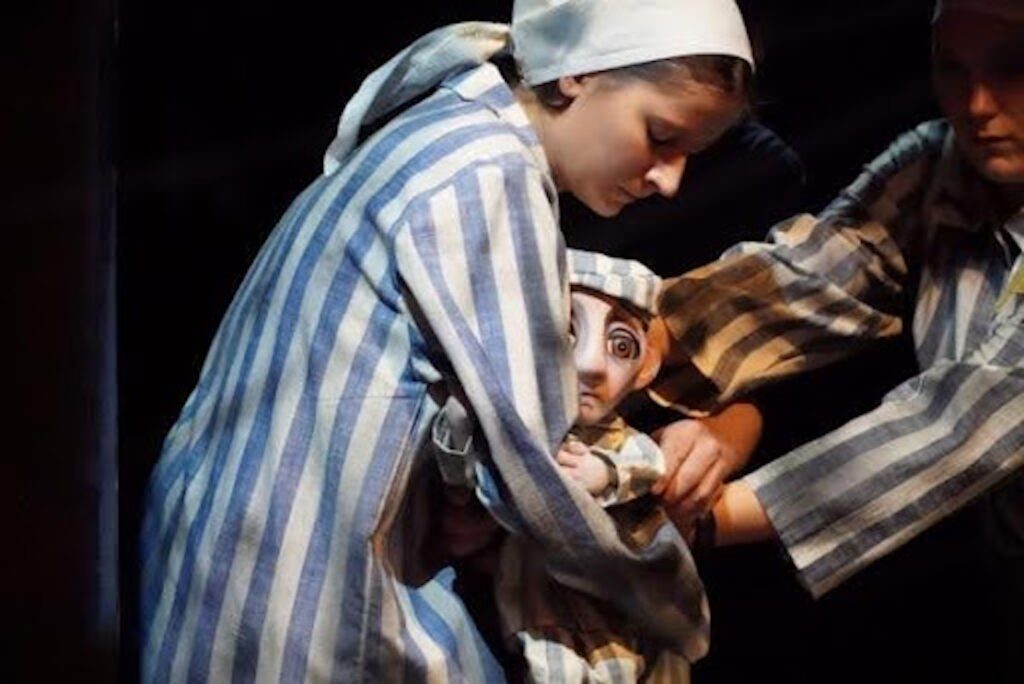

The absence of dialogue in the play allows for an ambiguous interpretation: perhaps the puppet is Esther’s child (see figure 1), or perhaps the puppet is Esther’s friend for whom she is caring for? We see the child as a little puppet in a carriage of bodies, among a pile of legs: the puppet child is searching for his relatives among the body parts. Esther tries to help the child, but the Nazi regime is ruthless. For the soldiers and guards, the child is only a small, irrelevant puppet, discarded by the war machine. In Auschwitz, Esther’s friends are symbolically turned into puppets and then destroyed by a monstrous machine implemented by its living minions.

The final moments of the performance of Kaddish often leaves audiences with an ambivalent feeling: the heroine, Esther, leaves the stage. I personally felt that the adversities undergone by Esther did not, in the end, break her. Nevertheless, her sad steps at the end of the performance seemed to show her walking towards death. Contrary to my interpretation of the ending, in a post-show discussion with the director, others insisted that the heroine survived the camp, was freed, and yet she left part of her soul back in Auschwitz.

The Russian production, which was the original basis for the production of Kaddish Memorial Prayer in Ukraine, became part of a wider discussion of World War II and Russian interests related to the war. If we compare the Ukrainian and Russian advertising and descriptions of the performance, we can see the differences in how each represented World War II and the Holocaust. In the Ukrainian version, grief is not only a means of processing the memory and trauma of that war. It is also currently connected to a collective hope for surviving the present-day, ongoing war with Russia. The Ukrainian framing is highlighted in descriptions of the play on the Odesa Regional Puppet Theatre’s social networks, thus: “This play cannot be played without heartache and cannot be watched without tears – but it must be played and watched—for the sake of memory, for the sake of the future” (Odesa Regional Puppet Theatre, 2021).

The topic of the Holocaust in the Ukrainian version of this production becomes an “antidote” to other narratives. The importance of this narrative is described by the Israeli historian, Yehuda Bauer: “Remembrance of the Holocaust is necessary so that our children are never victims, executioners or indifferent observers” (Odesa Regional Puppet Theatre, 2021).

There is one important moment in the Ukrainian production of Kaddish Memorial Prayer when one of the actors, who portrays a male prisoner in a concentration camp, sees how a very large puppet symbolically ends the lives of Jewish captives who have been turned into little puppets. This human character, after witnessing this symbolic action, desires power for himself—he becomes an accomplice of Nazism and rules his former comrades as part of the camp regime. He turns collaborator and helps to kill Jews in the camp as a means to his own survival.

The guilt of Ukrainians in relation to the genocide of Jews during the Holocaust is a painful topic, because there were indeed cases when Ukrainians became collaborators and killed Jews, along with Germans. But it is important to understand that this is part of a broader problem of collaborationism and anti-Semitism in Europe during the formation of totalitarian empires (Arendt, 1951), and not a particular problem of the predisposition of Ukrainians, as Russian propagandists try to present. This is why this performance was very useful for viewers in Russia, where they are constantly told that only Ukrainians can go over to the side of fascism.

Ukrainians often saved Jews during the Holocaust. And yet, the subject of Ukrainians as collaborators with the Germans during World War II is focused upon more widely. Among the artworks portraying Ukrainians who were not accomplices of the Holocaust, a sole example is the production titled Paper Ark. In the centre of this production, created by Ukrainian director Ivan Mykolaichuk, there is a description of the Ukrainian equivalent of Schindler’s List: the story of how the mayor of Chernivtsi saved thousands of Jews from deportation

The production Кaddish is not tied to nationalities or to discussions of national guilt regarding the Holocaust. Its advantage is precisely that it does not offer the image of a Ukrainian as either an accomplice or as a rescuer. The production generally moves away from national identification: in the play there are only characters wearing Jewish stars (later, in the role of prisoners) and Nazi characters.

A moment in the diasporic process of the Holocaust is tellingly captured when the audience witnesses how the Jewish people were broken and “uprooted.” They are presented with their houses torn apart, physically uprooted. The “roots” of people’s homes are shown in the literal sense: houses are held symbolically in the hands of the performers, with roots trailing (see figure 2). Following the loss of home, the second stage of their dehumanization is then revealed: the Nazis not only exile the homeless but mark them with yellow stars. From the standpoint of the Nazis, the mark of the yellow star brands the Jewish people as no longer human. In this process of dehumanization, when people put on yellow Jewish stars, they are symbolically, and in effect, “turned” into puppets. They have thereby been irrevocably changed by the monstrous war machine, represented by a giant puppet figure (see figure 3). At the moment of being turned into puppets, one of the victims chooses to survive. He throws away the Jewish star and becomes part of the force that controls from a position of power.

It is precisely this kind of Holocaust narrative that is needed in future theatre productions. It shows that characters “turning into an executioner” is not dependent upon race or nationality. No one race or ethnic or national group is more genetically predisposed toward betrayal than any other such group. Regardless of whether one is Ukrainian, Russian, or Jewish, horrific and terrifying circumstances can lead anyone of us to act contrary to our natural custom. The reception of the production of Kaddish Memorial Prayer in Odesa ultimately reads as hopeful, since the main character, at least symbolically, survives. This offers us the hope that survival is possible, although our current tragedy continues.

An important point drawn from this consideration of Holocaust narratives in the context of Ukraine’s current war is that, by working with the theme of the Holocaust, it provides an antidote to propaganda. Even with puppets, the experience of humanity can be reevaluated and trauma explored at a safe distance in theatrical manifestations, away from direct connection with the horrors. Using the capacities that puppets provide us, allows us a way to explore Ukrainians’ historical relation to fascism, a case which is currently actively inflated by Putin’s supporters. It is the puppets in Kaddish Memorial Prayer that show how dependent upon social bonds a character (of any nationality) can be, and, in order to survive, humans become complicit in acts of genocide. The production of Kaddish Memorial Prayerallows audiences who are experiencing trauma to explore what others have suffered but also how they survived against the odds. This liminal space of trauma, memory, and performance is hard to reconcile, as scholars Didier Plassard and Carole Guidicelli remind us, when reflecting on puppetry and the Holocaust: “Walking through the desolated landscapes of inhumanity, where death is the horizon and the ground we pace, puppets and marionettes might be the best travelling companions, reminding us of the frailty of our existences and making that journey liveable” (Plassard and Guidicelli 2022, 31).

Nataliia Borodina

Odessa National Polytechnic University

Dr. Nataliia Borodina is Associate Professor at the Department of Cultural Studies and Philosophy of Culture at Odesa National Polytechnic University and postdoctoral researcher at the Department of Theory and History of Culture of the P.I. Tchaikovsky National Music Academy of Ukraine. Her research interests include psychology of art, approaches to trauma informed art,and philosophical and cultural anthropology.

References

Arendt H. 1951. The Origins of Totalitarianism. https://cheirif.wordpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/hannah-arendt-the-origins-of-totalitarianism-meridian-1962.pdf

A must-see show in Khabarovsk: Puppet Theater. “Tevly Station.” 2021. (In Ukrainian.) https://transsibinfo.com/news/2023-04-27/spektakl-kotoryy-nuzhno-posmotret-v-habarovske-teatrkukol-stantsiya-tevli-2913959.

Axelrod, T. 2022. “Shlomit Tripp and her Bubales puppets make learning about Jewish culture fun for kids and adults alike.” Widen the Circle. https://widenthecircle.org/profiles/shlomit-tripp-and-bubales.

Duffy, Helena. 2017. [2022]. “Ukrainians in French Holocaust Literature: Piotr Rawicz’s Blood from the Sky and Jonathan Littell’s The Kindly Ones.” Eastern European Holocaust Studies, 1(1). https://doi.org/10.1515/eehs-2022-0017.

Halberstam, J. (1988) From Kant to Auschwitz. Social Theory and Practice. Vol. 14, No. 1 (Spring 1988), pp. 41-54 (14 pages)Published By: Florida State University Department of Philosophy . URL:https://www.jstor.org/stable/23558995

Holocaust Visual Archive. 2012. https://holocaustvisualarchive.wordpress.com/category/puppet-theatre/.

Jerusalem Post Staff. 2022. “Israeli puppeteer brings a different way to remember the Holocaust in the heart of Stockholm.” The Jerusalem Post. https://www.jpost.com/365days/-theatre/article-725777.

Kant, I.(1797) Über ein vermeintes Recht aus Menschenliebe zu lügen. URL: http://www.zeno.org/Philosophie/M/Kant,+Immanuel/%C3%9Cber+ein+vermeintes+Recht+aus+Menschenliebe+zu+l%C3%BCgen

Knepp, Robin. 2013. “Laughing Together: Comedic Theatre as a Mechanism of Survival during the Holocaust.” VCU. https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?referer=&httpsredir=1&article=4039&context=etd.

Krechetnikov, A. 2019. “Leningrad Blockade: Arithmetic and Politics.” BBC News. (In Ukrainian.) https://www.bbc.com/russian/features-46962532.

Markovits, Andrea. 2020. “Puppet theatre: A way to tell what cannot be told and to face pain.” Journal of Applied Arts & Health, Volume 11, Issue 1–2, 149–155. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1386/jaah_00027_7.

Margulies, A. 2022. “The Contemporary Jewish Museum Presents Oz is for Oznowicz: A Puppet Family’s History.” Contemporary Jewish Museum. https://www.thecjm.org/pages/404.

McLoughlin, K 2006. “Dead Prayer?: The Liturgical and Literary Kaddish”, Contemporary Jewish American Writers Respond to Judaism, Vol. 25 (2006),4-25: https://www.jstor.org/stable/41206046

Odessa Academic Puppet Theater. (In Ukrainian.) https://www.facebook.com/teatrPastera15a.

Pine, Dan. 2010. “Puppetry, comedy and the Holocaust merge in unique Fabrik.” The Jewish News of Northern California. https://jweekly.com/2010/01/29/puppetry-comedy-and-the-holocaust-merge-in-unique-fabrik/.

Plassard, D., and C. Guidicelli. 2022. “Haunted Figures, Haunting Figures: Puppets and Marionettes as Testimonies of Liminal States.” Skenè. Journal of Theatre and Drama Studies, 8(1), 11–33.

Public: “Real stories of the Holocaust.” Chernivtsi will show a play about the genocide of the Jews. 2022. (In Ukrainian.) https://suspilne.media/209570-realni-istorii-golokostu-u-cernivcah-pokazut-vistavupro-genocid-evreiv/.

Roitman, Ariel “The Phenomenology of Puppet Ontology in the Holocaust Performative” Etudes, Vol. 8 No. 1 2022 http://www.etudesonline.com/uploads/2/9/7/7/29773929/etudesdec2022roitman.pdf

Smalyushok, V. 2021. “With the support of RICC, the play ‘Anna Frank’s Diary’ was shown.” (In Ukrainian.) https://russia-israel.com/blog/pri-podderzhke-rikts-proshel-pokaz-spektaklya-dnevnik-annyfrank.html.

Solonin, Mark. “Blockade of Leningrad.” (YouTube, in Ukrainian). https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=plEaSn8YC2w.

The premiere of the play about the Holocaust “Tevly Station” took place in Khabarovsk/Telekanal Khabarovsk, 2021. (YouTube, in Ukrainian). https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EztF9zOCdss.

van den Bergh, Sophie. 2017. “To Appreciate the Perfection of the Machinery”: Rethinking the Notion of Barbarism in ‘Playful’ Holocaust Representation. In Subjects Barbarian, Monstrous, and Wild. Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill. https://doi.org/10.1163/9789004352018_013.