This report examines an interactive traditional performing arts project conducted in Osaka in January 2024, designed to inspire students to engage with and appreciate traditional arts in a globalized context. The project demonstrated that traditional performing arts can integrate modern creative elements while preserving their cultural essence, offering a replicable model for engaging younger audiences. By participating in production and performance, students overcame preconceived notions of traditional arts as “difficult and old-fashioned” and discovered their joy and value.

The study underscores the importance of hands-on educational experiences and innovative approaches that balance tradition with modernity to sustain interest in traditional performing arts. Educational initiatives, such as this project, play a critical role in nurturing future performers and expanding audiences. Addressing budgetary and logistical challenges is essential for broader implementation, ultimately democratizing access and fostering deeper appreciation for cultural heritage across diverse communities.

Seiko Shimura is Associate Professor, Faculty of Music, Soai University. She received a BA in musicology from Tokyo University of the Arts in 1999 and a PhD in design from Kyushu University in 2014, then served as a post-doctoral fellow at Graduate School of Kyushu University until 2015, followed as a research associate at Cultural Policy Program of National Graduate Institute for Policy Studies, Tokyo, until 2017. Her doctoral dissertation was published by Kyushu University Press in 2017 as Theory of Performing Arts Management: Aiming at Co-creation with Audience. Her current research projects include traditional performing arts conservation and promotion, and arts management education. In recent years, she serves as a member of the expert committee at the Osaka Arts Council, a board member of Japan Arts Management Association, and a member of the executive committee of Fukuoka Early Music Festival. She also served as the director of the Traditional Performing Arts Coordinator Development Program subsidized by the Agency for Cultural Affairs from 2019 to 2021.

Robin Ruizendaal was the director of the Taiyuan Asian Puppet Theatre Museum in Taipei, Taiwan, for over twenty years and is currently artistic director of the Taiyang Theatre Company. He holds a PhD in sinology from Leiden University in the Netherlands (Marionette Theatre in Quanzhou, Brill publishers, 2006). He has published widely on Asian puppet theatre (Asian Theatre Puppets, Thames and Hudson, 2009) and was curator of numerous puppet theatre-related exhibitionsaround the world. He has written and directed more than twenty modern and traditional Taiwanese (puppet) music theatre productions that have been performed in over thirty countries around the world. He is an honorary citizen of Taipei. In 2019, he was the recipient of the Prix franco-taiwanais of the Académie française. In 2024, he received the Taipei Culture Award as well as the Certificate of Recognition for Conservation of Puppetry Heritage by the Heritage, Museums and Documentation Centers Commission of UNIMA.

Introduction

This report presents an overview of an interactive traditional performing arts project conducted in Osaka in January 2024. The primary goal was to motivate and inspire students to engage in and appreciate traditional performing arts in the context of rapid globalization. The project demonstrated that these art forms can incorporate modern creative concepts while maintaining their essence. Additionally, it established a replicable model for engaging young audiences in traditional arts, highlighting the importance of accessibility, educational value, and joy of participation.

The preservation and transmission of traditional performing arts face critical challenges due to factors such as lack of performers, changes in industrial structures, and shifts in people’s lifestyles. Despite the urgent need to preserve the cultural diversity of each region of Japan, traditional performing arts are heavily reliant on local economic factors, cultural resources, and community support, making it challenging to substitute these with new mechanisms. Such challenges are common across traditional Asian performing arts. To address these issues, this study focuses on nurturing the next generation of practitioners and expanding audiences for traditional performing arts within the framework of university education.

Several challenges surround the education of traditional performing arts in Japan. In music education, for example, schools predominantly emphasize Western music, which often leads children to perceive Japanese scales as unfamiliar or unconventional from an early age. Furthermore, music teachers, who are typically trained in Western music, face significant difficulties in effectively teaching traditional Japanese or other Asian performing arts due to a lack of specialized knowledge and resources.

Another challenge is the lack of arts management education tailored to traditional performing arts. Despite the rapid development of public cultural facilities since the 1980s, the focus has predominantly been on infrastructure, neglecting essential aspects like facility utilization and arts management. Consequently, while efforts to train individuals in arts management have been underway since the 2000s, traditional performing arts have been overlooked as a significant genre within this field.

In light of these circumstances, the authors established the “Traditional Performing Arts Coordinator Training Project” in Osaka with funding from the Agency for Cultural Affairs from 2019 to 2021. The first project involved a series of public lectures tailored for working adults, with most participants in their 40s to 60s and a smaller group in their 30s. There was strong interest in traditional arts among attendees, with some continuing to practice in various genres. The project succeeded in developing arts managers; however, the limited participation from younger generations underscored the need for fostering an early appreciation of traditional culture among the general public. This situation underscores the motivation for the current research: to develop mechanisms within education for the younger generation to familiarize themselves with and learn traditional performing arts. The current study was funded by Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research (KAKENHI) 2023‒2025.[1]

Case study: Van Goghʼs Dream

To engage students in the production process and foster an active learning environment alongside professionals, in January 2024, we conducted a workshop on the stage production of traditional performing arts as part of the educational initiatives at Soai University. The students participating in this project are art management majors housed within the Music Department, who typically focus on concert planning, production, and organizational management theory. This workshop marked their first experience specializing in visual and puppet manipulation, as well as their initial involvement in the practical application of traditional performing arts.

The workshop had several primary objectives: first, to devise strategies aimed at nurturing studentsʼ interests in historical subjects and deepening their connection with their cultural heritage and, second, to explore the feasibility of modernizing traditional performing arts to achieve these objectives. Additionally, this study aimed to create a practical template for interactively engaging the young generation with traditional performing arts and to assess the acceptability of introducing modifications to traditional practices to appeal to younger people. Dr. Robin Ruizendaal of the Taiyuan Puppet Theatre Company in Taiwan, in performing and conducting research on traditional puppet theatre all over Asia from the 1990s onward, noticed a distinct lack of interest in traditional arts from the younger generation in most Asian countries. In their productions, as well as educational programs, the Taiyuan Puppet Theatre Company tried to both preserve the essence of traditional performance while simultaneously modernizing some creative elements. Initially, traditional language, music, story, and puppets are preserved, adding modern staging and lighting. Later, new stories are created with themes relevant to the performers and their audience. The ultimate goal is to inspire the performers and the audience rather than creating a clear distinction between what is traditional and what is not. The theatre can find its own way, as it is a very democratic institution that lives by the support of its audience. Drawing from the lessons from the Taiyuan Puppet Theatre Company’s work, the goal of the program described below, “Van Gogh’s Dream,” was to introduce participants to the fundamentals of staging a puppet play in the hope that they would enjoy themselves in the process of producing and performing a show, inspiring some to continue down this creative path.

1. Concept development

The planning process began in August 2023, and encompassed establishing the concept, gathering materials, identifying the theme, and determining the set-up of the stage. Invaluable insights were gained from looking at the model of the Taiyuan Puppet Theatre Company’s Shadow Theatre workshops, first conducted in 1999, when the Company discovered that shadow theatre offered an economical way for students to create paper shadows and perform in a classroom setting. Three-dimensional puppets are complex to produce and perform, while paper shadow figures can be relatively fast to both make and master and can incorporate both traditional and new elements. After an exchange program in Taiwan with Larry Reed of ShadowLight Productions in San Francisco in 2006, Taiyuan adopted Reed’s shadow theatre technique of using a large screen and halogen lights, opening the door to a new type of shadow performance with infinite possibilities. As opposed to the traditional small shadow screen used in most Asian countries, where a single seated puppeteer manipulates the puppets, a large screen provides an extensive surface and backstage area. The halogen light gives a sharp shadow projection of both actors and puppets on the screen. The projections of the shadow puppets and actors can become large or small depending on their distance from the light and move around more freely across the screen. Another great advantage to working with shadow puppetry is that it is relatively inexpensive to produce, making it easily accessible. Taiyuan used the technique regularly around the world, for example with artists of the Haida First Nation in Canada and with disadvantaged children on the outskirts of Paris. The combination of creation, performance, and visualizing stories through shadow theatre always had a positive outcome. The most extensive program developed by Taiyuan, “Touch Taiwan” (Chou Yi- Chun, Ruizendaal 2013, 2014), focused on Taiwan’s diverse Aboriginal legends passed down through oral tradition. The Taiyuan Puppet Theatre Company members were in residence at a tribal elementary school to create an original stage production (the project was supported by the Aborigine Council of Taiwan). The pupils learned to express themselves in their indigenous language, sing, make and manipulate puppets, and finally perform in front of an audience. Through their artistic expression, teachers, children, and the surrounding community affirmed their identity and strengthened their connection to each other through their shared culture. Video recordings (YouTube link: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BBngpuEUGvc&t=18s) vividly capture the enthusiastic participation of the children, the active involvement of the teachers, and the overall effectiveness of the outreach program, which continues to run. After every individual project, a roll of washi (durable and soft, hand-crafted paper) and a halogen light were donated to the tribe or school, so they could continue performing. In the following years, some schools actually bought professional projection screens, and they continue to make excellent performances.

This initiative provided a helpful reference for starting a similar project in Osaka, Japan. The primary objective of the 2023–24 project was to develop a portable, cost-effective framework for creating a shadow puppet show conducive to educational dissemination and adaptable to various regions and institutions. To ensure the workshopʼs success and the production quality, three professionals played pivotal roles: Ruizendaal contributed to scriptwriting and offered expertise in shadow puppetry techniques; designer Rain Chan, a designer from Taiwan, provided expertise in set design; and Japanese bunraku shamisen player Tomonosuke Tsuruzawa enriched the experience with live music. The character of Van Gogh, popular in Japan, was selected as a central character because of his profound love for Japanese art and as a creative element to inspire and motivate the students. This figure helped underline the idea that the tradition is alive and can incorporate new elements for a modern audience.

To create a visually captivating environment, the scenography combined washi paper screens with halogen lights. Washi paper diffuses light more evenly than cloth screens, reducing the harshness of the light source and casting a softer glow across the stage. While strongly associated with Japanese artistry, washi paper in this project was used to evoke a broader sense of Asian aesthetics, inspired by the diverse traditions of shadow puppet theatres across Asia. Machine-made washi paper from Taiwan was chosen for its affordability (approximately US$45 for 100 meters) and its unique properties that enhance the visual experience. Additionally, live music, an integral element of traditional performances throughout Asia, was woven into the show, enhanced by modern technologies through video, sound effects, and lighting. This combination of traditional and modern elements aimed to enrich the audience’s experience while acknowledging the various old and new influences on Asian shadow puppet theatre.

2. Outline of the script: Vincent van Gogh and Ihara Saikaku

Crafting a compelling script for theatrical productions necessitates careful planning and consideration. This project emphasized developing a plot rooted in historical context rather than creating a wholly original storyline. A variety of sources were explored to gather material for the script, including folktale collections, literature, and traditional performance repertoires such as bunraku[2], rōkyoku (narrative singing), and kōdan (rhythmic oral storytelling), as well as foreign folktales. Ultimately, traditional stories associated with Osaka were chosen as the foundation for creating scenarios.

The core of the production was an adaptation of Ihara Saikakuʼs Koshoku Gonin Onna (好色五人女,Five Women Who Loved Love, 1686).[3] This collection of stories depicts the tragic love affairs of five couples based on actual incidents that were widely discussed and well-known to the public at the time. While the book portrays the romances of young people forced to give in to feudalistic morality and institutions as tragedies, it also highlights the positive human desire for love.

The first of the five stories adopted for this project, “Onatsu and Seijuro” (お夏清十郎), is based on an actual incident that took place in Himeji, Banshu (now Hyogo Prefecture), in 1662. It is about an adultery case between Onatsu, the daughter of a merchant from the Tajimaya family, and Seijuro, the merchant’s assistant. Ihara Saikaku’s version of the tale achieved widespread popularity. Later, the playwrights Chikamatsu Monzaemon and Chikamatsu Hanji both adapted the story into plays for the puppet theatre.

In our project, Onatsu is reimagined not as the daughter of a merchant family in Himeji but as the daughter of a lantern shop owner in Edo (Tokyo). This choice allowed us to depict the escape of the lovers from Edo to Osaka and show the contrasting cultures of the two cities at that time. This thematic backdrop is where Van Gogh’s imagined journey to Japan intertwines with the historical narrative.

Vincent van Gogh, the Dutch post-impressionist painter, was deeply influenced by Japanese ukiyo-e prints, which inspired his use of intense colors, bold outlines, and unique compositions. Like many European artists in the late nineteenth century, Van Gogh was fascinated by Japonism—a Western appreciation of Japanese aesthetics. Although he never visited Japan, this production reimagines Van Gogh’s journey through time travel, allowing him to wander through the wheat fields of France and then travel back to Osaka during the Edo period. In Osaka, he encounters Ihara Saikaku, the renowned seventeenth-century Japanese author known for his satirical works and vivid depictions of urban life. In Dotonbori’s theatre district, Van Gogh and Saikaku meet and attend a play together, experiencing the tragic love story of Seijuro and Onatsu, written by Saikaku, on stage. The production symbolically connects Van Gogh’s longing for Japan with Edo-period drama, exploring themes of love, beauty, and cultural intersections.

3. Character modeling: Puppet making

The process of making puppets drew inspiration from shadow theatre. Traditional bunraku puppets are three-dimensional and crafted from hollowed-out wood, but shadow theatre requires a flat, two-dimensional surface. For this project, the puppets were designed in the style of woodblock prints. The characters Ihara Saikaku and Vincent van Gogh were created with their specific personalities in mind. While both are serious figures, they also bring humor to the show through their lines. The creation of Onatsu’s shadow puppets involved significant trial and error. Initially, we considered emulating the beauty standards of ukiyo-e portraits. However, since beauty ideals have evolved, traditional ukiyo-e aesthetics may not resonate with younger audiences today. Instead, we drew inspiration from the onnagata or women’s role type in bunraku puppetry, modifying the design to present Onatsu as a beautiful and relatable female protagonist.

In bunraku, puppets are categorized as tachiyaku (young adult male), onnagata, and others, with each role type featuring a head (kashira) tailored to the character’s age, gender, and social class. Onatsu’s kashira has an oval face, almond-shaped white eyes, and reflects the refined elegance of an upper-class woman as celebrated in bunraku. Our craftsman, Rain, devoted meticulous care to endowing Onatsu with charm and personality, ensuring that she would captivate the audience.

4. Crafting bunraku music: Insights from Tsuruzawa Tomonosuke

Live music is an integral part of traditional puppet theatres throughout Asia, with stories unfolding in harmony with the music. From the outset, shamisen accompaniment, as used in bunraku,was envisioned for this project. After several weeks of selecting candidates, Tomonosuke Tsuruzawa, a bunraku shamisen player, agreed to participate. In addition to composing the music and playing the shamisen during the performance, he was also responsible for guiding the students’ narration.

An interview with Tomonosuke Tsuruzawa on May 2, 2024 at the Bunraku Theatre shed light on his approach to composing music for the new production. The interview focused on how he integrates traditional elements from bunraku’s traditional jōruri style music and chanting with new and diverse influences. Tsuruzawa emphasized the importance of capturing the essence of “gidayū-ness”—gidayū being the word for the chanter in the bunraku theatre, here capturing the unique style of vocal expression in this form—while discussing key aspects of composing a new piece. He explained that while incorporating standardized jōruri verses (meriyasu) and melodies from various genres outside of bunraku is possible, simply stringing together existing fragments will not result in a coherent composition. Originality is essential, but creating a new musical score must be guided by an understanding of how to effectively integrate old and new elements. He noted that a broad knowledge of different songs can serve as inspiration in this process.

Tsuruzawa emphasized the significance of text, or words, as the foundation of the composition process. Composing is generally easier when working with Japanese text structured in 5-7-5 rhythms. In this project, Robin wrote the script in English, inspired by Ihara stories in Theodore de Bary’s English translation. Shimura then translated it into Japanese, and Tomonosuke made further revisions to ensure it sounded like natural Osaka dialect. Developing the show alongside translation allowed for greater flexibility in adjusting the lyrics to fit the music. Tsuruzawa stressed the importance of using the natural Osaka dialect in the lyrics for authenticity.

Tsuruzawa encountered challenges in helping students express themselves appropriately in the Osaka dialect as written in the script. The students from our university who participated in this project were mainly from the Kansai region (Osaka, Hyogo, and Kyoto). However, Kansai itself has a range of dialects, and even within Osaka, multiple dialects exist. Bunraku traditionally uses the Senba dialect, historically spoken by merchants in Senba, Osaka, known for its elegance and refinement. Each student’s accent required adjustments to achieve a natural Osaka dialect. Tsuruzawa emphasized the importance of effective articulation, guiding students on breathing, pacing, and delivery. He stressed the need for clarity to allow even first-time audience members to easily immerse themselves in the play.

5. Projection testing in Taiwan

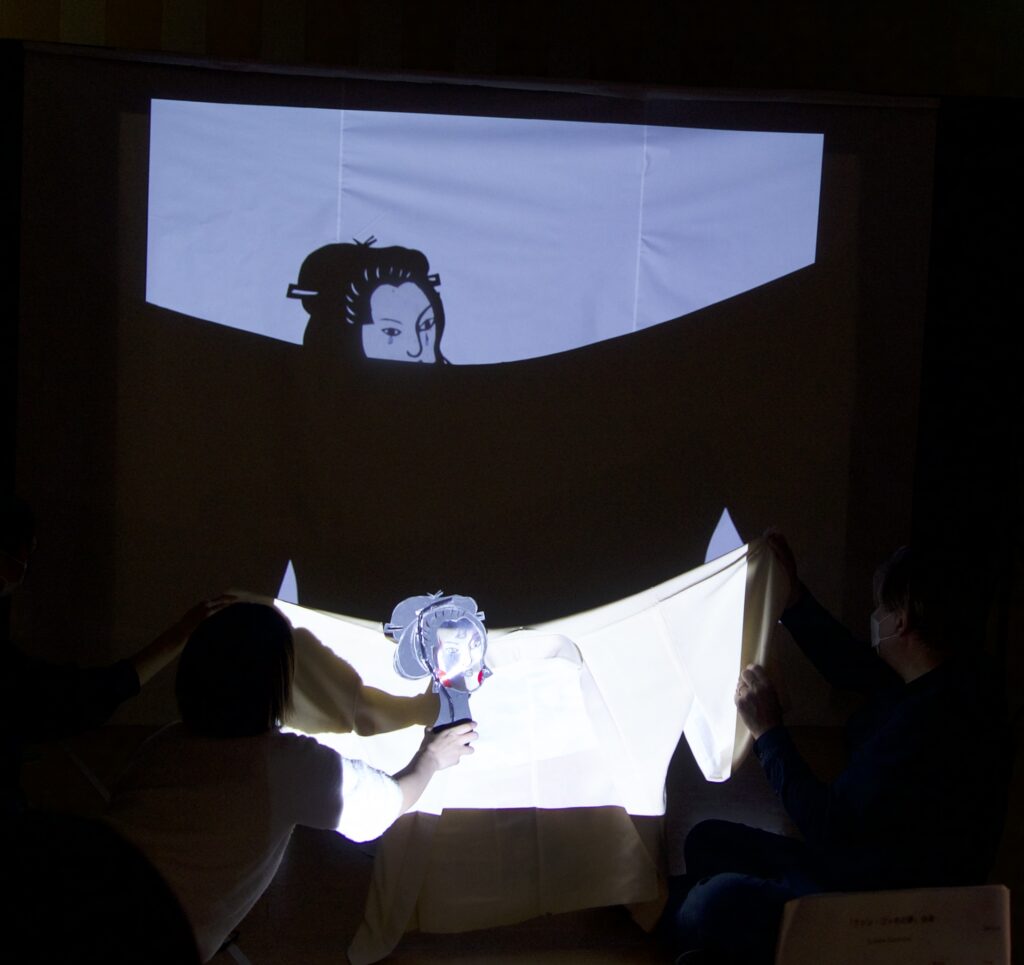

Several tests of projection techniques conducted in Taiwan in December 2023 by the creative team ensured the seamless integration of stage design elements, setting the stage for the subsequent workshop in January. The main goal of the tests was to figure out how to create the impression of a bunraku performance through shadow. One significant element in bunraku manipulation is the visibility of the three puppeteers who operate each central character. After conducting several trials, we developed a technique enabling the performer to manipulate the shadow puppet that allowed the performer’s hand to appear as an extension of the puppet itself. Although this is evidently far removed from the traditional bunraku manipulation technique done by three puppeteers, the performer does need to coordinate movements together with the recited text and music, as well as the projections. The further integration in the performance of projections of both the works of Van Gogh and of Japanese prints and the interaction of the shadow puppets with these projections was another experiment workshopped in Taiwan for enlivening the eventual performance in Osaka. We recorded a number of sound effects as well, such as the sound of the French countryside and Osaka street-market sounds; these were later combined with the projections.

6. Osaka Workshop

The workshop in Osaka ran for three days, from January 19-21, 2024, with seven students as core members and three as assistants. These students, majoring in arts management, typically study planning and production of stage performances and management organization theory while doing practical work managing concerts. This workshop marked their first experience with traditional performing arts, as they had the opportunity to perform a traditional art themselves, learning narration, puppetry, and other performance skills.

Initially, the students learned about the principles of shadow puppetry, focusing on the possibilities of expression through projection with a light source. They then created their original shadow puppets and experienced projecting them onto a wall. Subsequently, the students divided their production roles into the following categories: three narrators, one operator, two puppeteers, one general assistant, and one recorder. The recorder documented the project by taking notes, photos, and videos. All activities were conducted under the supervision of the experts.

Puppets of each character (Van Gogh, Saikaku, Seijuro, Onatsu, Oiran, Lion, etc.) were manipulated using a combination of various materials, including haori, small brushes, beads, etc. The haori, a traditional Japanese jacket worn over a kimono, was used to represent Onatsu’s right hand as she writes her letters, and also served as a curtain descending to symbolize the despair of Oiran (a courtesan) after losing her love, Seijuro.

Advantage of collaboration

The Japanese version of the script, completed in January 2024, was predominantly written in the Osaka dialect. This approach preserved the essence of “gidayu-ness,” while also creating a sense of familiarity for the students by aligning the text with their everyday language. As the students do not specialize in visual production, puppet making, or theatrical play, engaging professionals to help them with stage direction and puppet production was immensely beneficial. The students learned the techniques of shadow theatre manipulation under the guidance of experts. Notably, the experience instilled in the students a heightened awareness of timing and emotional resonance, as emphasized by Ruizendaal in his guidance on pacing during puppet manipulation. The improvisational nature of the shamisen music underscored the dynamic interplay between performers, diverging from the structured nature of Western musical scores.

The program aimed to enhance studentsʼ comprehension of traditional performing arts by actively engaging them in creation. Examples of their engagement with traditional arts included exploring contrasts between impressionism and ukiyo-e, understanding the aesthetic attributes of shamisen music and bunraku (albeit shadow) puppets, and delving into societal perspectives on life, religion, and social dynamics during the Edo period, and how these influenced the traditional arts of the time. Additionally, adopting an informal, first-name basis for communication, not usually the protocol within their educational environment, where one refers to both teachers and fellow-students by their last names, facilitated a sense of camaraderie among participants, further strengthening solidarity towards shared goals. Securing a more extended learning period could afford students the opportunity to learn about traditional body use and movement as well through instruction from Japanese dance performers and bunraku puppeteers. An embodied experience of these forms would provide students with invaluable insights into the traditional use of the body in theatrical performances.

This project underscores the need to address budgetary and time constraints to enable broader implementation within educational frameworks in the future. Proposing a customizable, yet replicable model, the objective is to democratize access to such educational programs, transcending geographical and institutional barriers.

Feedback from participants

To assess the effectiveness of the workshop, we asked participating students what aspects of their experience left an impression on them. One student tasked with narration remarked, “I learned to convey my emotions through my speech. It intrigued me that I could effectively communicate emotions to the audience by speaking more exaggeratedly than I initially thought necessary.” Another student reflected, “I found it particularly challenging to imbue my speech with genuine feelings and to employ language and intonation that deviated from my usual style.” A student responsible for video and sound operations shared her experience: “I thoroughly enjoyed collaborating with my peers to craft a unified performance. I vividly recall the process of creating the puppets and projecting them as shadows. The pressure of potentially making mistakes weighed heavily on me, knowing they could detract from the overall performance.”

Students tasked with operating the shadow puppets remarked how “manipulating the shadow puppet was quite challenging,” and, “I appreciated the opportunity to explore the novel method of expression using puppets and light for the first time. I found it intriguing that altering the distance between the light source and the puppet affected the size of the shadow and that the effective utilization of this technique could enhance the range of expression.” They added, “Crafting the shadow puppets was an enjoyable experience. The gestures conveyed by the puppets varied depending on how they were manipulated. Aligning our actions with Dr. Robin’s vision posed a rewarding challenge.”

Students’ comments also included the following perspectives:

Despite the language barrier, I found that I could effectively communicate with Dr. Robin and Rain-san through various art forms, including music, shadow puppets, and verbal expressions. This experience underscored the significance of the arts in facilitating communication.

Dr. Robin cultivated a friendly atmosphere for students, promoting an environment of open dialogue.

Despite the language barrier, under the experts’ guidance, we successfully conveyed our message through gestures and verbal communication. It was gratifying to achieve mutual understanding.

My primary mentor was Tomonosuke-san, and I appreciated the opportunity to closely observe his professional demeanor, including his language usage.

Initially apprehensive about communicating in a language other than Japanese, I discovered that effective interpretation (by Shimura-sensei) and simple English words and gestures facilitated communication.

Although initially anxious due to language differences with Dr. Robin and Rain-san, I found that effective communication was possible through gestures and nuanced expressions. By the end, we had developed a strong bond of trust. It was truly a pleasure to collaborate with them in crafting the workshop.

Overall, the feedback illustrates a comprehensive and multifaceted learning experience, highlighting the students’ growth in emotional expression, technical skills, collaboration, and cross-cultural communication.

Feedback from the audience

While our project was not widely publicized, a Japanese dance (kyo-mai) artist, Zuiou Shinozuka, attended the session on the final day. Her insights are as follows:

In January 2024, at a venue within Soai University, the performance created an atmosphere that transported the audience to the late Edo period. The sound of the wind blended seamlessly with the vivid primary colors projected on the screen, setting a tranquil yet immersive scene. The live shamisen performance further deepened this sense of time travel, its evocative melodies complementing the students’ narration and the movements of the shadow puppets.

The shadow play, featuring large and small puppets, moved in sync with the students’ narration, creating a surprisingly lifelike portrayal of human emotions. The interplay of the shadow puppetry, narration, and the evocative sounds of the shamisen gave the audience a feeling akin to stepping into a dreamlike journey—a fusion of historical Japan and the vivid imagination of an artist like Van Gogh.

The dedication of the students, who brought this production to life in a limited time, and the passion of the teaching professors, was deeply inspiring. This collaborative effort left a lasting impression, highlighting the transformative power of traditional performing arts education.

Conclusion

Traditional arts are often perceived by younger generations as “difficult and old-fashioned.” This project aimed to convey not only the beauty of traditional arts but also their significant value to previous generations. By actively engaging in production and performance, students overcame challenges and experienced the joy of participation. Traditional arts and theatre education should, therefore, emphasize personal, hands-on experiences to inspire and foster continuous interest and appreciation. We were in no way under the illusion that the production could mimic the traditional bunraku performance experience, but it was clearly a creative means of inspiring students to connect with traditional performing arts. The preservation and promotion of traditional performing arts require innovative approaches that balance tradition with modernity. Educational initiatives, such as the one undertaken in this study, play a crucial role in nurturing the next generation of performers and expanding audiences. By engaging students in the creative process and emphasizing the dynamic nature of tradition, such initiatives can ensure the continued relevance and vitality of traditional performing arts in contemporary society. There is a pressing need to address budgetary and time constraints in the future to enable its broader implementation across various regions and educational programs, ultimately democratizing access to traditional performing arts and fostering a deeper appreciation for cultural heritage across diverse communities.

Notes

[1] This research was supported by JSPS KAKENHI (grant number JP23H01014).

[2] Bunraku, also known as ningyō jōruri, combines tayū (narrative chanting), shamisen (a three-stringed musical instrument) performance, and ningyō (puppetry). While ningyō jōruri performances can be found throughout Japan, the form popularized in Osaka by Uemura Bunrakuken is specifically known as ningyō jōruri bunraku, or simply bunraku. The tayu and shamisen player, responsible for the gidayu-bushi or musical narrative, work closely together to deliver tense and breathtaking performances. Bunraku puppets are manipulated by three puppeteers, each controlling different parts of the puppet to convey subtle movements and emotions. With its sophisticated storytelling, bunraku encompasses both historical and secular themes, exploring topics such as love, tragedy, and moral dilemmas, and is an essential part of Japan’s cultural heritage. As the number of performers has severely decreased, the succession of this tradition is now supported through a state-subsidized two-year training system in addition to the traditional apprenticeship method.

[3] Ihara Saikaku (1642-1693) is considered one of the three great literary figures of Osaka, along with the haiku poet Matsuo Basho (1644-1694) and the jōruri playwright Chikamatsu Monzaemon (1653-1725). These writers helped to shape a literary culture that spread not only among the elite but also among merchants during the Genroku period. Although Japan was largely closed off during this period, trade with the Netherlands continued, allowing Dutch medicine, science, navigation, and astronomy to be introduced through Dutch books. This limited but impactful cultural exchange brought Western knowledge and technology to Japan. Ihara Saikaku’s haiku, which were characterized by their fresh and unconventional flavor, became known as “Dutch style” (Oranda-ryū). At first, this had a negative connotation, implying that they deviated from traditional norms. However, Saikaku actively embraced this label, and valued it, saying, “The haikai of the Dutch style is distinguished by its elegant form, profound heart, and fresh words.” (Ihara1678).

References

Chou Yi-chun and Robin Ruizendaal,, eds. 2013. “Touch Taiwan!” Taipei: Taiyuan Publishing, (book in English, Chinese, and various Aborigine languages with DVD of the performance).

______. 2014. “TouchTaiwan2”. Taipei: Taiyuan Publishing.

Ihara, Saikaku, 2016. Five women who loved love: Amorous Tales from 17th-Century Japan, trans. Theodore W De Barry. Tuttle Publishing.

https://www.tuttlepublishing.com/authors/saikaku-ihara/five-women-who-loved-love-9784805310120

Ruizendaal, Robin. 1999. “Mass Media and Asian Puppet Theatre in the 20th Century.” International Puppet Theatre Conference Proceedings. Taipei, Council for Cultural Planning and Development. 296-304. Ruizendaal, Robin. 2018. “Puppets, identity and politics in Taiwan.” International Opera Conference, National Taiwan College of Performing Arts. 285-305.