During 2021-22, we held a year-long virtual conference entitled “Women and Masks: A Transdisciplinary Arts-Research Conference” through Boston University. This report provides insights into the four weekends of virtual events, which featured presenters from around the world who offered a diverse range of content and experiential opportunities. The conference was inspired by the organizers’ interest in women’s complex experiences with mask practices. It highlighted the paradoxical potential of masks, often revealing the political and cultural narratives surrounding women. The intersection of these two themes exposed both exclusions and acts of agency while illuminating the complex phenomena related to acts of masking and masquerade. The conference has since evolved into the “Women and Masks Project,” with a reimagined and rebuilt website. Through this ongoing project, we have hosted both virtual and in-person events, made archived conference materials available, and created a platform for additional digital humanities resources related to the topic. We hope this will be a growing field of study. By developing an expanding database of artists, scholars, and performers, as well as bibliographic and pedagogical sections, we aim to make women’s work with masks visible and provide valuable resources for researchers and others curious about this topic.

Felice Amato is an assistant professor at Boston University, working at the intersection of visual arts, pedagogy, and performance. Amato’s forthcoming book explores women’s use of puppet and masks to explore themes of embodiment. She directs the Women and Masks Project at Boston University.

Introduction

During 2021-22, I directed a year-long virtual conference entitled: “Women and Masks: A Transdisciplinary Arts-Research Conference.” Based at Boston University, where I am an assistant professor in the art department, the conference consisted of four weeks of online events. In total, we hosted more than 80 presenters from across the globe: Japan, Belgium, Australia, Peru, Brazil, Puerto Rico, Mexico, Canada, Russia, Korea, Germany, the Netherlands, Italy, England, Bali, Ireland, France, and Nigeria. We also engaged over 500 participants in one or more conference offerings. Since the conclusion in April of 2022, we have hosted or co-sponsored additional events and rebuilt and added content to the website, transforming the foundation created into an ongoing digital humanities Women and Masks Project.

The conference emerged from the submission of a small Faculty Project Grant offered by Boston University Center for the Humanities. With the support of my department director and the School of Theatre, I was able to find additional partners at the university. The campus Arts Initiative’s Indigenous Voices Series, the African Studies Center, and the Kilachand Honors College all lent support. The structure I proposed was four thematic weekends. I was blessedly naïve with no concept of the labor––both meta and granular—required to host so many participants and events. Once begun, I was pulled into the excitement of the project. I found important support in a small group of people who shared my passion for the topic. Not only did they consult, host, and create materials, but they informed the richness of the content, bringing in new names and thematic connections. The weekends, which spanned the 2021-22 academic year, were September 24–26, October 30–31, February 11–13, and April 22–24. The original themes were adjusted to fit presenter schedules and the content of the submissions that we received. We anchored each weekend with one or more keynote speakers. These were Joan Schirle, Skeena Reece, Zina Saro-Wiwa, Ana and Débora Correa of Yuyachkani, and Paola Piizzi Sartori and Sarah Sartori. We then assembled panels and presentations and, whenever possible, included making and moving. There was a broad interpretation of the themes in the form of scholarly presentations, mini-performances, the screening of videos, artist talks, interviews, workshops, and studio visits. We endeavored to include global perspectives and embraced divergent ideas that could broaden the idea of the mask and complicate common assumptions. This was crucial to the rigor with which we approached the subject and our desire to push this field of inquiry forward.

We were a small team. Fundamental to the conference was Alexandra Simpson, a theatre maker and then PhD student at York University in Toronto, who had also been a participant in the Sartori workshop. Our conversations were instrumental in the conception and shaping of the conference. An accomplished actor and teacher with extensive experience in masks, Simpson brought her many areas of expertise, hosting talks and experiences, as well as presenting on her own work. Elsa Weihe, the K-16 Education Outreach Program director at the Boston University African Studies Center, collaborated on the February weekend, which was conceived to be specifically global in nature. In addition to submissions received, we worked to identify presenters who could offer two days of African-centered content specifically for educators. This addition reached another audience, providing meaningful professional development for teachers.

Another founding supporter was Deborah Bell, Professor Emeritus of Theatre-Costume Design at University of North Carolina at Greensboro and author of two books on masks. She was active throughout, hosting and giving presentations in her areas of expertise, such as “The Ascendency of Masquerade in Our Digital Age.” Bell brought the history of two previous American mask conferences, held at the University of Iowa in 2001 and Southern Illinois University in 2005. They are described extensively in her book Mask Makers and Their Craft: An Illustrated Worldwide Study (McFarland 2010).

The conference manager, Paula Mans, a BU alumna and artist, hosted events and presented a mask curriculum that she designed for early childhood. She helped to design a fairly elaborate website with a biographical page for each presenter. We built a mailing list of over 800 subscribers and sent out fliers to promote each event, with the additional goal of cultivating visibility for our presenters beyond the events. Recently, undergraduate researcher and project assistant Anna Paradise revised the website and created a digital archive of the schedules of events and ephemera, which is available here: https://sites.bu.edu/womenandmasks/about-the-project/conference-archive/.

In addition to Boston University entities, the conference was endorsed by UNIMA-USA, a chapter of the international puppetry organization, Union Internationale de la Marionnette, a sponsor of this journal. Scholars in the field, Claudia Orenstein and Kathy Foley, both on the UNIMA-USA board at the time, consulted on content and structure. Foley also contributed one of the experiential, interactive presentations which helped break the fourth wall of the Zoom platform. It was entitled, “Wayang Golek (rod puppets) and Topeng (masks): From One, Many.”

While the virtual format constrained us in some ways, it allowed for global participation. Among the many global presenters, Galia Petkova from Eikei University in Hiroshima, Japan presented “The Japanese Female Mask Okame ‘Plain-looking Woman.’ Origins, Usages, Significations.” She discussed female archetypes in Japanese mask culture, in particular the case of Okame, described as a plain-looking, smiling woman featuring a broad brow and swollen round cheeks who is said to bring luck. Her research examines Okame’s origin and historical and contemporary usage. German researcher Freda Fiala presented “Masking ‘Chineseness:’ The Performance Works of Xie Rong (Echo Morgan).” Rong, also in attendance, draws from Fluxus and Eastern Philosophy. Commenting on the body politic and eco-feminism, she uses her body as a canvas, marking it with a range of materials: Chinese ink, red lipstick, and even her own breast milk.

The virtual format also allowed the screening of many short video pieces, such as Israeli puppeteer Orit Leibovitz Novitch’s video Rawness. We received permission to show Advice to Myself 2: Resistance, a collaboration between Heid E. Erdrich and Pulitzer Prize-winning writer Louise Erdrich. Polina Borisova, the creator of the work Go!, also held a talkback. Other screened performances included works by Abby Holgerson and Alice Nelson. Many of these remain available to view through links to our site.

Women and Masks: An Enduring Fascination

Women’s experiences in the realm of material performance, including puppets and masks, has been an abiding interest of mine. The specific focus on masks became crystalized in 2019, when I participated in a month-long seminar with Italians Paola Piizzi Sartori and Sarah Sartori. The mother and daughter were now at the helm of the family’s Centro Maschere e Strutture Gestuali (Mask and Gestural Sculpture Center) and Museo Internazionale della Maschera Amleto e Donato Sartori (Amleto and Donato Sartori International Mask Museum). Known throughout the world, Amleto Sartori developed the pedagogical Neutral mask in collaboration with Jacques Lecoq and was a key part of the revival of theatrical masks and commedia dell’arte in twentieth-century theatre. His son Donato continued the artistic innovations and rigorous research of the family. At the time that I met them, Donato, who was Paola’s husband and Sarah’s father, had recently died. Perhaps unsurprisingly, with the death of the last male in the family, there were many that thought the family’s prominence in the mask world had come to an end. The mother and daughter, however, had been intimately involved in the creative, curatorial, and pedagogical activities for decades (Paola since her early twenties and Sarah since birth) and were profoundly knowledgeable and committed to continuing the family’s work. I was intrigued by how they would navigate the male-dominated world of mask making and masked theatre in general.

The marginalization and even outright exclusion of women from various aspects of mask practices is quasi ubiquitous. In theatre, for example, not only in commedia dell’arte, but also in noh theatre, women are only slowly and recently beginning to integrate into these historical forms as performers. (This was something Petkova included in her talk.) In the case of commedia, for example, the traditional female characters were never masked and, apart from a few exceptions, the range of roles for women were limited. So, was their success in taking on male roles (playing them either as men or transforming the characters into females). And perhaps less visible behind the scenes, those who design and craft the objects central to the performances are usually men. Requiring years of apprenticeship and opportunities to develop their skills and artistry, they exist within networks that are difficult—albeit not impossible—for women to enter. In fact, in the US there is still the problem of erasure or the fading of names from collective consciousness. Jenny West’s talk about her mother Joceyn Herbert, a seminal figure in postwar twentieth-century British theatre, was enlightening. Herbert is not well known outside of certain theatre circles despite her role in the rebirth of masks in the twentieth century. She designed the sets, costumes, and props and reshaped postwar theatre in the UK through “her minimal settings, in which realistic details were placed within simplified settings” (Hogan n.d.). Equally transformative was the way that Herbert engaged as a designer: “Her approach altered the way directors and audiences came to view stage design and contributed to a fundamental shift in the relationship between writer, director and designer” (Hogan n.d.). West’s talk, “Joycelyn Herbert’s Use of Masks in the National Theatre Production of the Oresteia, 1981,” was part of a panel on prominent women in Modernist theatre who, despite the impact they had, are not well known. Annette Thornton presented “Lotte Goslar and Bari Rolfe: Finding a Voice in the Silence of the Mask.” Jennifer Sheshko Wood’s talk was entitled “Tanya Moiseiwitsch: Innovating Stage Design in the 20th Century.” It is ultimately through hearing their names and seeing images of their work that they secure a place in theatre history.

In fact, where one finds masks, one often finds boundaries of many different types that prevent parity in participation. In the folkloric dances and ritual performances and ceremonies of many countries, men have and continue to dominate, often playing female characters. The reverse is rarely seen. The instances in which women take hold of a mask are complex and revealing. In her article, “Masks and Powers,” anthropologist Elizabeth Tonkin says, “Masks are themselves transformations, they are used also as metaphors-in-action, to transform events themselves or mediate between structures” (1979, 241). Often the act itself of putting on the mask, where there has been a prohibition or simply an exclusion, can seem reactive versus generative. This then becomes a part of the content embedded in the act itself; it is not simply a woman who is now masked––it’s charged with the momentum summoned to move into that territory.

In 2021, masks were in the Zeitgeist. Even before COVID-19, it seemed that everywhere, contemporary artists—many of them female—were worldmaking through forms of masquerade. Instagram had created mask stars, such as @fashion_for_bank_robbers, who showcased the performativity masks bring to jewelry and fashion. Painter Megan Marlatt and her Big Head Brigade of capgrossos (“big heads” in Catalonian) highlighted the mask’s ability to activate public spaces. The large helmet masks she learned to make in Barcelona (both self-portraits and pop culture personalities) playfully confounded viewers’ sense of the human by disrupting proportionality. Brazilian-Swiss artist Melissa Meier’s dreamlike masks, meticulously assembled of seeds and other matter, melded the acts of posing and performing. This called up the long history of female surrealists’ engagement with masks (Claude Cahun, Leonor Fini, and Leonora Carrington, to name a few).

This phenomenon of material worldmaking has emerged in symbiosis with social media. The cellphone and apps like Instagram have democratized distribution of work, allowing artists to frame and curate their own practice (or curate that of others). The masking is carnivalesque, fantastic, or surreal. But it is material as well, grounded often in real spaces that we peek into. It’s complicated, to say the least: our phones are flooded with often decontextualized imagery from all regions and time periods (some never having existed outside code generated by AI). It has created a quasi-disembodied experience of masquerade; held in the palm of our hand, the small, jewel-like illuminated window pulls us in and leaves the body behind.

Masks continue to be central to activism, subversion, and protest. Tonkin argues that “We can see what Masks do and why they are particularly capable of doing it. . . . Masking, acting through its own paradoxes, is a richly concentrated means of articulating Power” (245-46). The Guerilla Girls’ use of masks, for example, and the resulting political and phenomenological effects reveal the enduring trickster potential of the mask, core to many traditions. Born of the necessity to hide their identity to avoid retaliation, their fierce and hairy masks also disrupted the gaze. Likewise, Pussy Riot, the Russian feminist protest and performance group, made use of brightly colored, handmade balaclavas, often with roughly cut holes for the eyes and mouth. These multiplied their presence, hid their identities, and created an aesthetic tenor of the carnivalesque. Feminist theorist Rosi Braidotti wrote:

You put on your mask, you become Pussy Riot, you take it off, and you no longer are Pussy Riot. . . . That’s the becoming-political: the masked faces of Pussy Riot, who are both over-exposed celebrities and anonymous militants carrying on what must feel at times like a losing battle, sustained under the threat of constant retaliation, repression and violence. In putting on the balaclava you don’t hide yourself but rather express another political subjectivity, which allows you to unveil and debunk the working of power and despotism (9-10).

The use of masks activates the paradoxical potential of the objects to anonymize and to identify, to make numerous, to make singular, to make seen, to confront, to protect, and to hide. And, when women use them, they create specific points of contact between the two themes that bring the political and cultural text of the female body into focus, highlight acts of agency, and, in this way, illuminate what masks can do in a focused way. Innumerable instances, across time and place, reveal that the act of covering is charged for women.

Arts Research and the Transdisciplinary Approach

The conference was conceived as the integration of the scholarly with a multi-modal, transdisciplinary, arts-based research approach. Art research, theorist Patricia Leavy says, “[adapts] the tenets of the creative arts in order to address social research questions in holistic and engaged ways in which theory and practice are intertwined” (2020, 2-3). Empirical knowledge, derived from the senses and from doing, perceiving, and reflecting, had obvious value for the specific focus of this conference. It is through the embodiment of the mask—and the temporal and affective experience of the wearer and observer—that the mask realizes its transformative potential.

Despite the virtual format required at the height of the pandemic, we did not want to lose the body in the days-long flow of virtual events. To that end, we began the entire conference with a session by Jennifer Frank Tantia, a somatic psychologist and dance/movement psychotherapist, entitled “Looking Out and Seeing In: A Journey Through the Body.” Tantia facilitated a participatory process of awareness to and through the body in preparation for the use of masks. Alexandra Simpson also led experiential movement workshops. Continuing this throughout the year, with many such events. In February, German puppet and mask artist Alice Gottschalk led an online movement experience. Another participant, Jean Minuchin offered an immersive workshop entitled, “Gender: Power and Sensitivity through Masks.” An art history professor who attended the workshop said it helped prepare her for a curatorial project by providing her a direct and embodied experience with the objects. In fact, as an amateur myself, I felt strongly about providing the space for someone with no experience to have a powerful, personal experience with a mask. This approach resonated with many. One participant commented in an anonymous survey: “Women artists and issues, the conference was amazing! I connected on an academic, scholarly level and as an artist and woman.”

As an art educator, I felt it was important that there be accessible hands-on workshops. It was important that people experience the potential of movement and the body to change what is perceived as a static mask. Likewise, they should understand how the architecture of the mask asks for certain movements as a character is developed. Italians Chiara Durazzini and Nora Fuser, both mask actresses, gave demonstrations of the development of their masked female characters, specifically highlighting the connection to the female body. Speaking to the practical concerns in the design of masks which are meant to be worn, Alyssa Ravenwood and Crystal Herman gave presentations on the nuances of design and fabrication when creating wearable masks for real actors.

We began the conference with a pre-conference event, part of a two-part workshop with Canadian mask maker Melody Anderson. Anderson facilitated the making of a papier-mâché mask based on a technique she developed over years in Canadian theatre. Masks require testing on the body. Because the workshop happened over eight days, Anderson could respond to the way the completed masks worked––a fundamental part of the pedagogy of mask building. She also gave an artist talk about her entry into masks and how she developed her non-toxic technique. In addition to a movement experience, Alice Gottschalk joined theatre artist Linda Wingerter and led participants in examining the full potential of paper and cardboard, through techniques that each has developed.

We also ended the conference with mask making. The last weekend featured the Sartoris, who gave a multisession masterclass on mask design. Participants met with Sarah and Paola to write character sketches and to translate them into a clay prototype. The Sartoris demonstrated the complex ways that physiognomic principles––specifically traces of animal features within a human face––have been used for character development. They brought attention to line and plane which helped the participants refine the masks for theatrical use, which is different from a carnival costume. Despite being on Zoom, the opportunity to hear people’s intentions and feedback created a community of learners.

February

The February weekend is an example of the thematic approach we strove for. While the programming throughout the conference was intentionally diverse and global, Elsa Weihe from the African Studies Center and I endeavored to develop a weekend with a decidedly global focus. We specifically sought out programming relating to African masquerade, which would disrupt simple stereotypical notions of both the aesthetics and uses of African masks. The weekend started with a screening of British-Nigerian filmmaker, artist, and curator Zina Saro-Wiwa’s 2020 performance-lecture-film, Worrying The Mask: The Politics of Authenticity and Contemporaneity in the Worlds of African Art.

[The film] navigates the moral, philosophical and cultural conundrums that arise from the very existence of contemporary traditional African art. A large part of Saro-Wiwa’s artistic practice explores the masquerade traditions of Ogoniland, her ancestral ethnic group from the Niger Delta. Yet Saro-Wiwa’s hybrid identity has forced her to consider how African masks live concurrently in the West and in present-day Africa and how these African art worlds impact one another especially at a moment when restitution is being demanded. (UCLA 2024)

In the lecture, Saro-Wiwa brings attention to the dilemma posed by contemporary traditional mask carvers for collectors and the art world (both in Africa and the West). These carvers innovate within a genre, seeing the replication of traditional mask styles as a form of preservation of culture and history for the next generation. She raises questions about the fraught conceptualization of “authenticity.” She discussed the overlapping sensibilities necessary to do the work of curating:

What can these objects after all truly communicate to a curator who is not emotionally and spiritually open as well as academically rigorous. The two approaches must come together. . . . The African masquerade made today or a thousand years ago throw up profound storytelling challenges. They challenge us aesthetically, politically, temporarily, racially, and spiritually. It is time we meet the ontological provocations they represent with verb, imagination, and boldness (UCLA 2024).

Saro-Wiwa teased out the aspects of her own engagement with masks that relate to being a woman and/or being from the region (while having grown up in the UK). While the masquerade in Ogoniland, like most African masquerade, is performed by men, Saro-Wiwa brought complexity to this issue. Describing how women tend to be more attached to Christianity in the culture and are, therefore, less transgressive of the proscribed gender roles that limit them from direct participation with the mask (except a rare female who resists social pressure and joins one of the masquerade societies), Saro-Wiwa also suggests that women can curate and study masks. There is also power in the commissioning of a mask as a way of participating in masquerade indirectly. This is something that both she and a local woman have done (in the case of the latter it was the Mami Wata mask, which appears in her film). This financial sponsorship––even ownership––offers a sort of access to masks. While the carvers she has worked with are male, the exhibition she curated of masks by contemporary carver Promise Lagiri included a room full of traditional danced Ogoni masks called “Waakoo,” which feature a breastfeeding figure on top. The mask was originally commissioned to celebrate and “encourage mothers to breastfeed for at least for a year and three months.”

In the Q&A that followed, Saro-Wiwa addressed the need for Africans to appreciate and respect their own culture—including the contemporary makers like Lagiri. She argues that Africans living in the UK, for example, must embrace what happens in the village. Africans who demand repatriation must also care about the fate of masks and other objects and the complexity of their interpretation wherever they are geographically located. Saro-Wiwa was asked about the advice given to American educators teaching about Africa to avoid the mask and masquerade as topics because they reinforce stereotypes. Her response was surprising. She sees this framing as inherently destructive. She says: “If you are afraid of that level of Africanness, you have a problem with Blackness in and of itself.” This outside perspective might be well-meaning, but it premises the notion that there is something wrong with masks and masquerade. She argues that anyone who argues for the avoidance of these aspects of African culture has inadvertently revealed that they believe that their culture is superior.

Among the presenters the following day was poet and scholar Chinyere Okafor of Wichita State, who has written books challenging simplistic narratives about women’s exclusion from masquerade in her native Nigeria. Most recently, she published Gender, Performance and Communication: African Ikeji Mask Festivals of Aro and Diaspora (Africa World Press 2017). In her talk, she also spoke about her approach to using masks in her Women’s Studies classes to empower the students to enact various scenarios. Echoing the complexity that emerged throughout the weekend, Susan Elizabeth Gagliardi of Emory University gave a talk on the African masquerade and, among other topics, the evolving ways it has been studied and framed art historically. In her new book, Seeing the Unseen, she looks at ambiguity in the dynamics of West African objects, assemblages, and performances.

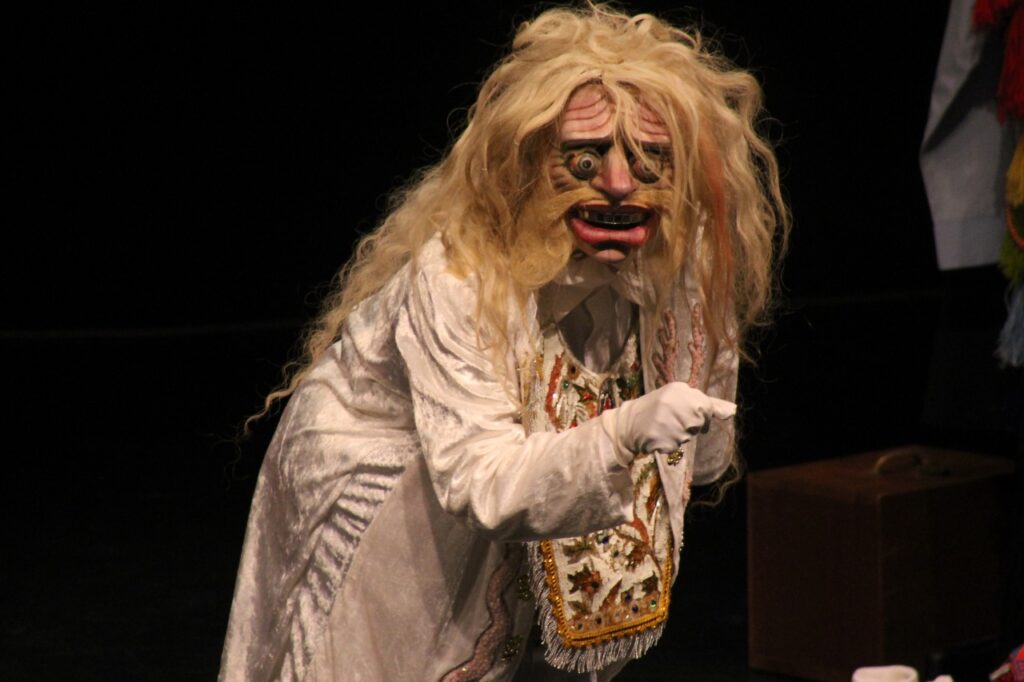

Figures 5 and 6: El Caporal (left) and Débora Correa with the El Caporal mask (right) from the production Contraelviento. (Photos: Courtesy Grupo Cultural Yuyachkani)

During the February weekend, we had a second keynote event on Saturday night which featured scholar Anne Lambright in conversation with sisters Ana and Débora Correa from Peru, who have been the subject of her research. They described their founding involvement with the theatre collective, Grupo Cultural Yuyachkani. The politically-committed group has been working at the forefront of theatrical experimentation since 1971. The Correas also spoke about drawing upon pre-Columbian female imagery to develop characters and described in detail their process of using masks as a form of ludic therapy with women who have suffered various forms of trauma in their native Peru. As one of the participants commented: “Yuyachkani is one of the most important theatre groups in the world. Their work is significant and needs to be shared globally. American theatre students are mostly unaware of theatre in other places in the world. It’s essential to introduce students to the richness of the global theatre world.”

Also in February, we hosted Big Queen Laurita Dollis of the Mardi Gras Indians tradition in which elaborate beaded costumes, adorned with feathers, are imagined, designed, and created new each year. Dr. Cynthia Becker interviewed Dollis about the way that the costuming is created and her participation in the mutual aid-style structures that the carnival activities nurture. Participants perform royalty with specific decorum that includes gestures of respect and honor between and among the groups. Dollis’s talk highlighted the ambiguity of what counts as a mask. While the face is not usually covered in this practice, Dollis described the internal transformation––and that of social interactions––that she experiences when she performs her regal identity in the Wild Magnolias. “I made my suit, and I wore it. . . . The royal-ness was unbelievable. The respect that queens get is unbelievable. And from that time, I never stopped” (Dollis). It also shifted mask and masquerade from the object to the effect: What does this adorning and disguising do? How does it change one’s experience of the body?

Surfaces

The mask has its own materiality and specifically its own surface. The relationship of this surface to the body shows up in compelling ways. The tension that exists between human skin and any other material can trigger the uncanny. Masks can be used to explore even subtle (yet profoundly marked) distinctions in the juxtaposition of human and high-tech flesh. Current technology allows masks for robots to convincingly mimic human skin (with the sex industry a non-insignificant stakeholder). Assistant professor of graphic design at Oakland University, Dho Yee Chung, a presenter in our September weekend, was part of a themed panel on the intersection of fashion, contemporary art, and masquerade. For the panel, she screened her 2018 video, “A Prototype of Desiring Being.” It features a figure in a cartoon-like mask and body stocking that says, “You can project your desire onto my skin and then you can own my image.” Her alter ego wears this costume and mask to embody confusions, fears, and desires in response to the projection of social expectations:

My work entails ideological, cultural, and aesthetic reflections on the meaning and complexity of the new forms of a surface. The use of masks raises the question of authenticity and how hyperreality can be easily fabricated. . . . Furthermore, I am particularly interested in images of women encoded with the desires of consumer society. (Chung)

She described the signification and materiality of the “extended” surface she created, using surface as a shelter, filter, mask, and camouflage.

Themes like surface, core to the mask, were recurrent. In October, artist and professor Lucy Kim discussed materiality, surface, and authenticity in conversation with artist threadstories. Kim creates molds from people’s bodies and uses thick paint to create bas-relief portraits made of draped monochromic castings of acrylic color. Threadstories is a well-known Irish artist whose very material-based practice exists primarily on Instagram, where she has 80,000 followers. There she brings to life her crafted fiber masks by posing and animating them (while protecting her anonymity). She frames her artistic practice in relation to the prevalence of surveillance and facial recognition, rejecting while also, in some senses, embracing social media’s realization of exposure as a sort of currency. She discusses her uneasy relationship with the very platforms on which she has essentially self-created:

Along with the online curated life comes the constant grooming to overshare, I believe personal privacy is precious and it is fast becoming a thing of the past. The hashtag I use “anticeleb’’ encapsulates some of this for me, the striving for exposure or fame for fames sake. The work I was making during my degree was also about privacy in the early 2000’s. I have continued this stand of enquiry as I find it an intriguing area to consider. (Iverna n.d.)

Social Media, Masks, and Worldmaking

Technology has altered our social interactions, and therefore the forms of masking. The sophistication of filters that alter the face continue to evolve, revealing human fascination with the uncanny and the grotesque and anxieties about aging, beauty, and gender. In October, we began the weekend with the performance practices of Skeena Reece, the daughter of the late Tsimshian Nation mask carver Victor Reece. Skeena Reece, a Canadian of Métis/Cree and Tsimshian/Gitxsan descent, has been engaged in a broad, multi-disciplinary practice over the past decades. It has included performance art, spoken word, writing, singing, and “sacred clowning”––the performance of a character who says or does something transgressive to impart wisdom and test the fragility of a community’s beliefs. Engaging with the traditional and the extremely contemporary, @victimprincessmother on TikTok is a series where Reece uses her own body and the mask of social media filters. In seconds-long performances, she distorts her face and voice to perform a variety of tropes of Native women. Simultaneously self-referential, satirical, painful, and provocative, Reece uses this form of masking in these sometimes-uncomfortable vignettes to embody the very stereotypes and aspects of contemporary Native experiences while playing the trickster. She is both inside and outside the culture. For example, she dresses in her own found object knock-offs of stereotypical Native dress to enact the role of Baby Yoda’s mother. In doing so, she dives headfirst into the complexity of claiming Baby Yoda as Native, something some online communities have done. One cannot help but laugh at many of the vignettes, while realizing that the humor and the critique are entwined and happening on many levels. And that all viewers (and even Skeena herself) are implicated in distinct ways, depending on their positionality.

High fashion can become a form of worldmaking, drawing upon a sense of the utopian and the dystopian––and everything in between. One of our presenters, Carina Shoshtary runs the page fashion_for_bank_robbers. A German-Iranian artist, Shoshtary discussed how her material explorations led her from training as a goldsmith to becoming a mask maker who continues to dialogue with jewelry. She curates for research purposes, saying: “I like that the makers of masks and headpieces come from so many different creative backgrounds. . . . This opens up boundaries between the creative fields: sculpture, fashion, makeup art, jewelry . . . everything just melts together.” In her talk, she also highlighted the collaborations which drive many of her explorations. On her Instagram, she makes space and visibility for other mask makers that she admires, creating a virtual community which includes other conference presenters: Mammu Rauhala from Finland and Canadian Miya Turnbull.

There are surprising connections between the high tech and the most ancient aspects of the mask. In “Seeing Together but Differently: From Visuality to Participation in a VR Art Installation,” Manduhai Buyandelger described how masks are widely used to create alternative realities, with examples ranging from computer-mediated virtual reality to traditional shamanic rituals in Inner Asia that she has written on in her book, Tragic Spirits: Shamanism, Memory, and Gender in Contemporary Mongolia (University of Chicago Press, 2013). “Such creative masks help wearers to suspend their everyday identities and assume new ones. The dark swinging tassels of the Mongolian shamanic headdress, for instance, obscure the face of the shaman during spirit-possession rituals as the practitioner improvises personae from a distant past. Audiences must construct the identities of the spirits through the performance of the mediating shaman—who is simultaneously familiar and strange.” Buyandelger’s forthcoming projects include “Being Someone Else” on Immersive Technologies such as VR and other collaborations in Mongolia.

Joan Schirle and Hidden Lineages

In a final conversation after Skeena Reece’s October event, there was a touching moment. We had invited those gathered to switch over on Zoom from viewer to participant. Our September keynote Joan Schirle was in attendance and she turned on her camera. She proceeded to produce a small carved mask that Skeena’s father Victor Reece had given her after a performance in Vancouver decades before. This encounter between Schirle and Reece was an example of the connections, lineages, and legacies that were revealed. This was highlighted from the very start with our choice of Schirle, whose name quickly emerged as an ideal inaugural keynote speaker. We were thrilled when Schirle accepted our request, playfully showing up on screen in a range of masks and even poking fun at the academic framing of the conference. An accomplished artist who entertained us with her amazing performances, she was also a teacher, mentor, and collaborator to many. She was a founding artistic director of Dell’Arte International School of Physical Theater, started in Blue Lake, California, in 1976. It continues to be known for creating original works through the devising process and using traditional physical theatre techniques to explore the contemporary. One of three events, Schirle led a workshop on Sunday called “Schirle’s 17 Solid Suggestions for Superb Mask Performance,” which include:

SPIRIT of the mask—Honor it, reveal it. STILLNESS There is power and mystery in the stillness of the mask, not constantly in motion. SURROUND—The mask is a fragment, a corner of a larger picture to be framed with costume. SURRENDER— to the mask. Allow yourself to be ‘inhabited’ by the spirit of the mask. SUSTAIN—The hardest: to sustain the life of your character through all its actions, reactions, and transitions.

We didn’t know that Schirle was sick when she participated in September. However, a few months later we got word that she had passed away after a long illness. We turned the spring weekend into a memorial for her, drawing people from across the globe to share memories.

Schirle shaped the conference in many ways, connecting us to former students and colleagues, such as Alissa Ravenwood and Judy Slattum. Through Joan, we also met Alicia Martínez Álvarez, who founded the Laboratorio de la Máscara in Mexico City (1997) where she has been the director for more than 20 years. She has also been a professor at the National School of Theater Art and the University Theater Center of the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México. Martínez Álvarez screened and discussed her poetic documentary, Laboratorio de la Máscara: El Arte y Sus Objetos (Art and its Objects), which is still available through the project website along with a translation we commissioned. Martínez Álvarez has created masks for many productions and graciously allowed us to use images of her compelling masks across the site.

In addition to teachers and students, there was also the lineage of family. Mothers and daughters as collaborators showed up several times in the conference, such as Paola Piizzi Sartori and daughter Sarah Sartori. It also included Anna Shishkina, the Russian director of Mr. Pejo’s Wandering Dolls, one of the oldest street theatres in Russia, and her daughter Frosia Skotnikova. Another mother-daughter connection was that of Jenny West and her late mother Jocelyn Herbert.

Masks and Political Engagement

Women’s use of masks in connection to power and politics was woven throughout the conference. It was not inconsequential that the conference happened during the pandemic as well as in the midst of a movement of racial reckoning. Milwaukee based artist Kay Reese spoke about her project entitled “Mask-Off.” The compellingly glitchy scanner-based distortions she captured from moving faces (often in PPE) are metaphors “for the pandemic of racial indifference and violence against Black people.” She has also addressed the invisibility of women as they age, exacerbated by skin color.

Examining another form of strategic mask use: obscuring one’s faces, Amber West presented “We Play Our Way, I’m Proud to Be Me: Masked Performance Among Contemporary Female Rappers.” A poet, educator, and feminist scholar, West’s talk about the female masked rapper Leikeli47 illuminated the long history of masking in rap and the specific ways Leikeli47 deploys it as a woman in a male-dominated field.

Papel Machete’s work-in-progress, On the Eve of Abolition, and the conversation between the company members Sugeily Rodríguez Lebrón and Deborah Hunt, also highlighted the way that the theatricality of masks and objects can do real political work. Created in Puerto Rico, the piece critiques the carceral system and advocates for prison abolition. Dutch performer and director of the company Hotel Courage, Katrien van Beurden, joined a Zoom session along with many from her internationally-based troupe to talk about their use of masks for social action in conflict zones.

Trying to define mask reveals ambiguities. Butoh, for example, while not using a mask object, calls attention to the expressive potential of the face and body in tandem, in exaggerated forms that depart from the quotidian. Sarah Bernstein, interdisciplinary artist, astrologer, and poet discussed her work entitled, “Karen,” which uses “the gestural language of masked theater traditions, monologue, Butoh dance and astrology,” to explore the social media meme. Masks, Joan Schirle reminded us, require gesture, energy, commitment, and play that is extra-ordinary and not pedestrian: they live in exceptional space. This was mirrored in the face and body of Bernstein, whose exaggeration separates her from the ordinary, even as she explores pop culture.

The Body

It is difficult to talk about the mask without discussing the body. Clelia Scala, an Ontario-based visual artist, whose practice includes puppets and masks, spoke not only about her artistic practice but about the interesting space she inhabited while both becoming a mask builder and struggling to overcome an eating disorder that impacted her ability to see herself accurately.

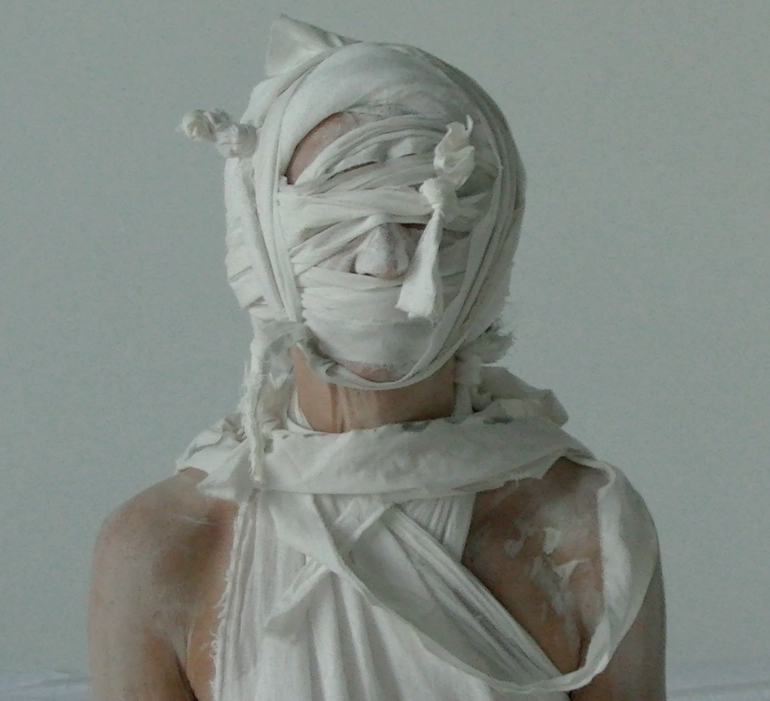

With the female body, come many other themes such as menarche, motherhood, and menopause. Vanessa Benites Bordin presented “Tikuna Masks in the Worecü Female Initiation Ritual,” describing how the masks are an essential element in girls’ first menstruation, one of the primary rituals of that society. The ceremony celebrates female fertility through a recognition of the significance of menarche, as well as the fertility of the land. Another event that referenced the female life cycle was a presentation by Athene Currie, our last conference presenter. The Australian artist and film-maker reminded us of all the rich gestural ways that we might mask with her documented performances that involve wrapping the self as a visual metaphor for female aging, menopause, posthumanism, eco-feminism, and bodily ego. Interestingly, a student in her mid 20s found this the most moving of all the presentations.

Even the breast made appearances. In an unforgettable opening scene in Skeena Reece’s October performance, she ceremoniously removed a Baby Yoda doll from bubble wrap and breastfed it! This image was echoed during Sarah Sartori and her mother Paola Piizzi’s talk when Sarah’s infant daughter demanded to be nursed during the discussion.

Gaze

Women have not always performed in public spaces with masks. Some have chosen to use documentation of performance as their medium. Erika Herrera, for example, described the process of exploring her Mexican American heritage and assuming an identity through costuming for a series of photos called “Becoming the Buffalo: Exploration of the Self and the Alter Ego,” in which she staged and documented the metamorphosis, often with blurred double exposures. She, Melissa Meier, and Athene Currie engage in solitary performances. Witnessing them only through documentation interrogates the notion of what counts as performance. Is posing performing? This, in turn, opens up conversations about women’s relationship with the camera lens, gaze, and private documentation of the self.

The Women and Masks Project

A different kind of visibility is that which we have and still attempt to foster on the website and mailings. Cheryl Henson recently spoke of making women theatre artists (past and present) “discoverable” by naming them even when one can’t elaborate fully on their contributions. It is impossible even to list all of the names and contributions to the conference in this article and so I urge people to examine the archive and the database. Also, though our program was robust, it suggests a larger field of inquiry. To that end, in the two years since the conference ended, we have created the Women and Masks Project. Conceiving of the resources generated as curated arts and humanities knowledge and data with potential value to researchers, it seemed logical that we should maintain and even build on the repository, which could inform and enhance existing research in the area of women and masks. With the help of Anna Paradise, the website has been redesigned and conference materials archived to be accessible. Due to our arrangements with presenters, we couldn’t archive the recordings of events themselves. We have added a bibliography of books and articles that engage the topic of women and masks, including works by conference participants, as well as a page specifically geared towards pedagogy.

The momentum of the conference encouraged us to host additional events. In 2023, we offered an in-person residency with Sarah Sartori and Paola Piizi Sartori, who gave two talks and a three-day workshop. The project website and social media account provide a platform for events and a hub for exchange. In many ways the conference was facilitated by the global shift to virtual events during the pandemic. It became an accepted medium of engaging and most people were fluent in accessing events through virtual platforms. This facilitated the conference’s global scope and we have continued to host virtual events because of their affordances. In January of 2024, Women and Masks cohosted “Les Masques: A Conversation with Three Francophone Mask Artists” with UNIMA-USA. The work of one of the three presenters, Céline Pagniez from Belgium, had been screened during the conference and she discussed her new work with masks and unhoused women. We also co-sponsored a live-streamed panel at the Italian puppetry conference festival, Arrivano dal Mare!, on the topic of women and autobiography in figure theatre, which is available on the website.

Ultimately, the responses of participants signal a continuing interest in the Women and Masks Arts-Research Project and a space for this interdisciplinary area of inquiry and connection. The comments from people who attended the event perhaps do the best job of summing up the breadth and impact of the overall experience of the conference:

The presentations were extremely high caliber, and it was amazing to have access to many masters of mask without cost. Because the subject was approached through many lenses, including visual artists, performers, historians, educators, social commentators, and accessed practitioners from around the world it was an incredibly rich experience.

[I] found the diversity in each presentation compelling, inspiring and engaging. The historical background was a rich layering element that added insight and meaning to the process of making the various styles of masks and how they have been used in past and in present times to affect the audiences for which they are intended. I so appreciated the depth of generosity and extensiveness in the lesson planning resources and other materials shared in the educational venues (Paula Mans and Marie Darling, Susan Elizabeth Gagliardi’s presentation also) and the creative and applied techniques demonstrated (Kathy Foley’s presentation was enthralling!), the materials suggestions and explanations demonstrated (Linda Wingerter). The keynote speakers (Zina Saro-Wiwa’s film was so polished and thought-provoking), and other professional performance insights and differences in the styles, construction and purposes from Latin American presenters, the Russian group and the Italian commedia to the Canadian presenters, and Bali/Sri Lankan puppetry. ALL were so fascinating to hear about and see in practical use (Alyssa Ravenwood). The use of masks in concept photography also resonated with me (Kimberly Callas, Melissa Meier, Erika Herrera) and I have always appreciated the therapeutic element of mask-making (Clelia Scala).

References

Braidotti, Rosi. 2015. “Punk Women and Riot Grrls.” Performance Philosophy 1, no.1: 239-54.

https://doi.org/10.21476/PP.2015.1132, accessed September 3, 2020.

Hogan, Eileen. n.d. “About the Jocelyn Herbert Archive.” https://www.jocelynherbert.org/time-line/, accessed 5 March 2024.

Iverna. n.d. “threadstories.” https://www.iverna.ie/interview/threadstories, accessed February 15, 2024.

Leavy, Patricia. 2020. Method Meets Art: Arts-Based Research Practice. New York: Guilford.

Tonkin, Elizabeth. 1979. “Masks and Powers.” Man 14, no. 2: 237–48.

UCLA International Institute. 2024. The 2020 Coleman Memorial Lecture–worrying the mask: The politics of authenticity and contemporaneity in the worlds of African art. Available from https://www.international.ucla.edu/institute/event/14387, accessed March 3, 2024.