Wakka Wakka’s Animalia Trilogy: Animal R.I.O.T., The Immortal Jellyfish Girl, and Dead as a Dodo. By Gwendolyn Warnock and Kirjan Waage. Directed by Gwendolyn Warnock and Kirjan Waage. Jellyfish and Dodo also written with help from the ensemble. Chicago International Puppet Theater Festival, Chicago, Illinois, January 18-28, 2024.

Wakka Wakka’s completed Animalia Trilogy was performed in full for the first time at the Chicago International Puppet Theater Festival in January 2024, uniting three distinct but thematically linked productions: Animal R.I.O.T. and The Immortal Jellyfish Girl (both of which had already premiered elsewhere) and Dead as a Dodo, which premiered at the 2024 festival. Differing in performance style and production format—the trilogy slowly scales up from the minimalist solo-performance of R.I.O.T. to the animated projections and musical numbers of Dodo—the three pieces stand alone but are nonetheless conceptually and narratively linked through their critique of anthropocentrism, a worldview that centers homo sapiens at the expense of the natural world. The trilogy delivers an urgent warning about the consequences of our self-centered speciesism, employing the audience’s empathy for the non-human and non-anthropomorphic puppets as a means of problematizing humanity’s seemingly innate narcissism.

Can the human race change its current course and nurture the environment rather than extinguish it? Or will we push science and technology to their limits, annihilating the planet and ultimately ourselves? Is it possible to undo the damage we have caused without leaving a destructive trail of unintended consequences? In posing these questions, the Animalia Trilogy transitions from “a guerilla-style, eco-manifesto” (the Chicago Festival’s description of Animal R.I.O.T.) to a sci-fi biotech fairy tale (The Immortal Jellyfish Girl) to a mythic hero’s journey through the underworld of extinction (Dead as a Dodo). Each performance critiques the blindness of humankind in a different way, linking our current apathy to the potential future horrors of the untested biotechnologies we think will deliver us from our own inertia.

The trilogy’s winding narrative follows the Fantastic Mr. Fox (“the real one!” he announces), who is portrayed by Kirjan Waage (one of the writers, directors, and the company’s puppet designer). Waage portrays Mr. Fox by wearing a ski-style mask in the shape and color of a red and white fox, making him simultaneously an anthropomorphic Fox and a human anonymously masquerading as a Fox. With a distinct accent and mild demeanor, the Fantastic Mr. Fox serves as the trilogy’s Everybeing, conscience, comic-relief, and narrator. Mr. Fox talks directly to the spectators, leading them politely through his manifesto in R.I.O.T., serving as the onstage storyteller for Jellyfish’s futuristic folktale, and attempting to help fix humanity’s mistakes in Dodo. Encompassing the entire trilogy is the warning that Mr. Fox gives viewers at the beginning of R.I.O.T. while explaining that the name of his activist group stands for “Animal Resurgence In Our Time! Because if it doesn’t happen in our time, then we are done for, finito, kaputt, game over!”

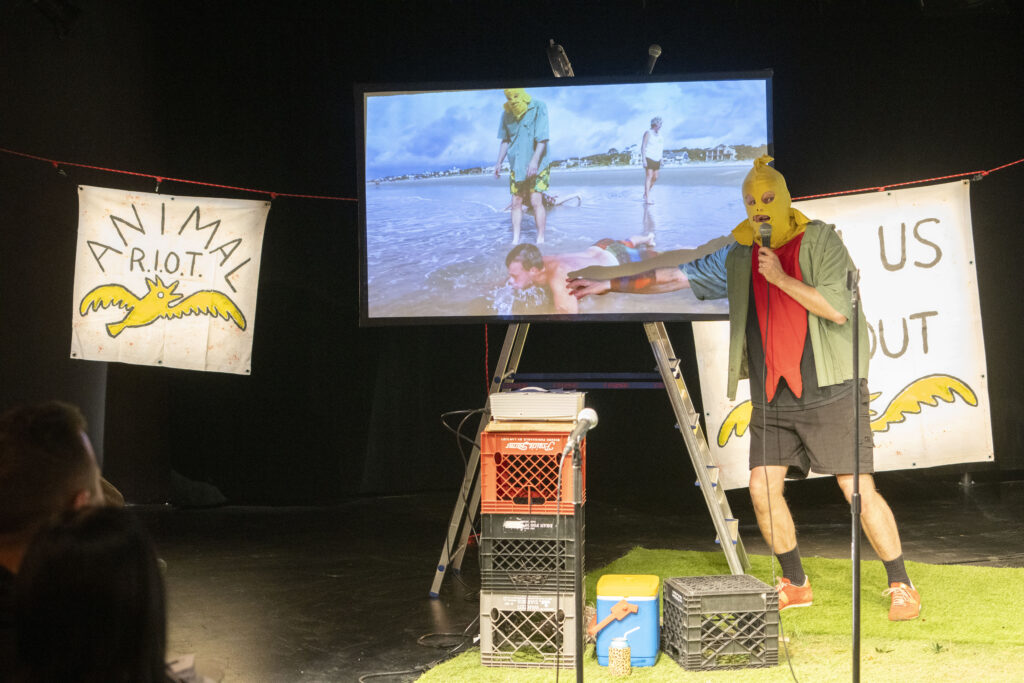

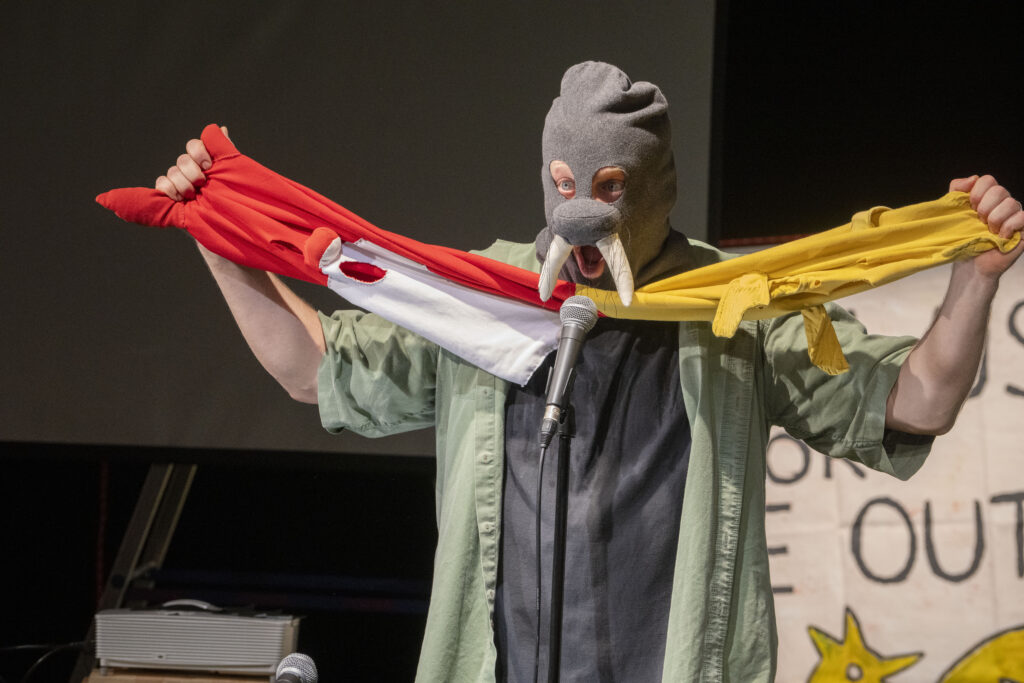

At the Chicago Festival, Animal R.I.O.T. performances were located in an intimate theatre space designed to look like Mr. Fox’s messy yard, with (fake) grass, a cooler, crates, and a projector and screen spread around the lawn outside a camper. Mr. Fox welcomes patrons to the Animal R.I.O.T. gathering, and over the course of the meeting observers are offered donuts and even a beer by different members of Animal R.I.O.T. who have shown up to argue about how to deal with humans. Waage portrays all the supporters of Animal R.I.O.T. by using animalistic ski-style masks of different colors in a tour de force solo performance. The back of each mask is sewn to the front of the next mask, and Waage pulls each one over his head in succession as the play continues.

In addition to Mr. Fox, the Animal R.I.O.T. adherents include a yellowfish, a walrus, an elephant, a turtle, a koala, and a jellyfish, and Waage uses a distinct voice and accent for each of them, allowing characters to speak at any time after their initial appearance. Waage simply puppeteers their masks, still attached and now hanging down in front of him, while the characters converse with each other. Like Mr. Fox, each masked character is both an anthropomorphic animal and a human using the anonymity of the mask to expound an ecocentric viewpoint.

Animal R.I.O.T. does not end on a particularly hopeful note, and The Immortal Jellyfish Girl takes place five hundred years afterward in a future that illuminates the cost of environmental inaction. The dystopian futuristic planet is barren due to high levels of radiation, and hominins have only survived through modifications. There are now two types of human species: the technologically enhanced “Homo Technalis,” who reside in a fascistic city controlled by the Doyenne, and the bio-enhanced “Homo Animalis,” ineffectually led by an intelligent Turtle in an underground hideout. The Turtle (the same bioengineer who was a member of Animal R.I.O.T.) is portrayed not by a mask but by a puppeteer in a full turtle costume, completely covered by a turtle shell with a detachable turtle head. The size and weight of the Turtle is juxtaposed to the Doyenne, who is only a head and an arm—both completely detached—because she was largely eaten by the Turtle’s ecoterrorist bioworms. The disparity is obvious: the Turtle is a substantial, weighty force with no power of his own, while the Doyenne is a despot with absolute authority but almost no physical form. In contrast to the planetary wasteland, the diversity of puppets suggests that life always finds a way. The question posed by Jellyfish is—at what cost? Is there too high a price to pay for the survival of our species or genus?

As narrated by Mr. Fox, Jellyfish becomes a tale of star-crossed lovers attempting to rebalance the natural world. The title character, Aurelia, is an Animalis girl who has a human appearance but occasionally grows polyps that detach as rod puppets and are placed in tanks of water to evolve into a kaleidoscopic array of life. The reason Aurelia’s polyps grow into new life is that the Turtle is not only an ecoterrorist but an eco-Frankenstein. The Turtle created Aurelia out of the DNA of numerous animals including the Turritopsis dohrnii, known as the immortal jellyfish because it can resurrect as a polyp if it dies as a medusa. Aurelia consequently represents the furthest limits of bioengineering, and the Romeo to her Juliet is a Technalis boy who grows giant insect wings because he is forced to work in the most irradiated areas of the city. Bug—as Aurelia names him—represents a bridge between the two factions, a Technalis who is also pushing bio-evolutionary limits.

Both Aurelia and Bug are portrayed by muppet-adjacent, costumed, cloth puppets that are manipulated bunraku-style by multiple puppeteers (“hidden” in head-to-toe puppetry costumes). As the puppets slowly transform, spectators witness both the beauty and the costs of evolutionary survival. The radiation is killing Bug, and unbeknownst to Aurelia, Turtle has bioengineered her to destroy the Technalis when she reaches her Medusa stage. As she moves closer to this evolutionary milestone over the course of the play, the puppet is slowly transformed and deconstructed while becoming beautifully lit from the inside, resembling both a glowing jellyfish and a certain mythic gorgon who turned people to stone.

Stories of star-crossed lovers seldom end happily even when immortality is a possibility, and Mr. Fox intervenes in an attempt to change the ending, reanimating Aurelia and positing a hopeful, rather than a destructive, conclusion based on the fact that puppets, at least, can be brought back to life. In Mr. Fox’s version, Aurelia and Bug ensure that the age of the jellyfish arrives and brings life back to the oceans. Huge hanging columns of white plastic bags, bobbing up and down like jellyfish, drop from above the stage at the end of the play, leading viewers to hope that Mr. Fox’s intervention has been successful.

The final play in the trilogy, Dead as a Dodo, proceeds to question the efficacy of intervention even if it is well intentioned. The play opens with the puppeteers—once again “hidden” in head-to-toe puppetry costumes but now also covered in sparkles—crowding together to form an earthy, cave-like environment out of which a bone appears, as a rod puppet, followed by the skeletons of a Neanderthal Boy and a Dodo. The skeletons are soft, cloth puppets that are manipulated by multiple puppeteers through the bone-cave environment created by the glittering bodies of the puppeteers themselves. The Boy is missing his right arm and left leg and is looking for bones to replace them, but when he finds a bone, another skeleton immediately steals it. The urgency of the Boy’s search becomes clear when he realizes that his missing leg has been replaced by a leg made of the same black sparkly earth as the cave. The Boy is vanishing and returning to dust, and he admits to the Dodo that he is afraid of disappearing and being forgotten, informing viewers that extinction is not the end—further erasure is possible. Yet the Dodo not only remains intact; she suddenly starts growing feathers. While the Boy is fading, the Dodo is resurrecting.

In the underworld, extinct creatures are terrified of being completely eradicated, but the Boy slowly realizes that transformation is not the same as elimination. Extinction has always been a fact of life on earth, long before human beings arrived. If the Dodo is a reminder of humanity’s mistakes, the Neanderthal Boy is a reminder that extinction is a part of evolution. As the Dodo continues to return to life, she transforms from a skeleton to a fully fleshed (and feathered) animal. The Boy tries to help her, and they begin a journey through the underworld to complete the Dodo’s resurrection in an intriguing parallel to Orpheus and Eurydice. When the Boy finally notices that the Dodo has become warm, she suddenly disappears upward as though transported by an alien abduction. A single feather falls on the Boy, who is now alone in an underworld that is increasingly chaotic. Characters he met on his journey are swept helplessly across the stage, and the ferryman Charon mourns the loss of his beautiful fish (a very large puppet that appears to be iridescent when “under water” beneath a black light) who has returned to dust as the Styx has changed course.

As the Boy (re)turns to the earth of the underworld—a reversal of the Dodo’s journey—a woolly mammoth appears upstage, the size of Mr. Snuffleupagus and completely composed of sparkly dust. The Mammoth picks up the Boy’s skull and ribcage and gives them to the puppeteers, completing the Boy’s own transformation from corporeal extinction to ineffable immateriality. Riding the Mammoth, the Boy visits the Dodo in the lab where she has been resurrected and has hatched a chick under the watchful eyes of Mr. Fox, Dr. Yellowfish, and the Walrus (all portrayed by small stuffed puppets). The Boy tells the Dodo that he is proud of her and that he is going to cross galaxies with the Mammoth, but he wanted to see her first (and her baby!). The scientists cannot see the Boy or the Mammoth and discuss what else they should resurrect, deciding against hominids. They want to give other species a chance before humans kill everything.

Unlike Orpheus, the Boy sacrificed himself for the Dodo’s resurrection after braving myriad underworld obstacles, including a Keplerian astronomer who tried to help them. It turns out that being extinct is not the end; the true end is to transform back into the stars. Is this a sign that the Neanderthal is gone forever, and if so, is that truly bad? Just as important, is resurrecting animals driven to extinction by humanity a good idea? Mr. Fox, Dr. Yellowfish, and the Walrus clearly have good intentions and are attempting to fix humanity’s mistakes. Nevertheless, they cause chaos in the underworld because they are interfering with the natural order just as the original extinction did. The Boy is following in the footsteps of Ishtar, Odysseus, and Aeneas, but unlike his Mesopotamian and Greco-Roman ancestors, he does not return to the land of the living. Instead, his journey might best parallel that of Dante emerging from the Inferno just before dawn on Easter and seeing the stars. Unlike those who had journeyed through the underworld before him, Dante’s goal was not resurrection but Paradise. In a scientific world, perhaps returning to stardust in the heavens is the appropriate next step after extinction, no matter how that extinction came to pass. As the boy tells the Dodo in the final line, he is finally able to fly.

Each episode of the Animalia Trilogy builds on the previous plays methodologically and philosophically. Mr. Fox is our Everybeing, but he does not have all the answers. Wakka Wakka actually offers Umwelt workshops (described by Dr. Yellowfish in Animal R.I.O.T.), and they offer their Bioeccentrism Manifesto for free download (inspired by the 1922 Manifesto for Eccentrism, which also inspired the production style of Animal R.I.O.T.). The trilogy wonders whether humanity is fated to use science and technology to destroy ourselves and the earth. “Fixing” our mistakes by scientifically resurrecting extinct animals has its own unintended consequences. Is there still hope? Animal R.I.O.T. indicates that if we are unable to change now, we are doomed. Nonetheless, Mr. Fox’s intervention in Jellyfish posits a reseeding of the oceans, from which all life on earth originally sprang. Is such a thing possible? Or, as Dodo suggests, will we simply all become one with the stars?

Jesse Njus

Virginia Commonwealth University