Wayang Workshop: Balimodule, Denpasar, Bali, May 2-7, 2023, UNIMA-USA and University of California, Santa Cruz

A workshop in Denpasar in May 2023 by I Nyoman Sedana and I Made Georgiana Triwinadi introduced foreign theatre practitioners to Balinese wayang kulit. Instruction focused on four character types and culminated in a performance based upon Arjuna’s Meditation. The workshop included visits to noted Balinese dalangs (puppet masters) at their sanggars (home studios) and performances of topeng, kecak, and trance dance enacted within temple contexts.

Karen Smith is a recent President of UNIMA-USA. As a member of UNIMA International’s Executive Committee, she has been Vice President (2016-2021), President (2021-2025), and Editor-in-Chief of the online trilingual World Encyclopedia of Puppetry Arts (https://wepa.unima.org). Her MA (Flinders University, 1982) was on Modern Indian Drama. Her puppetry work in India has been with Shri Ram Centre (1982-1985), Jan Madhyam (1985-1987, 2001-2005), Ishara Puppet Theatre (2001-2003) and in Indonesia on Javanese wayang kulit purwa at Sanggar Redi Waluyo (1999-2000). Journal notes of Damon Young and observations of Kathy Foley and other workshop participants inform this report.

Following the 2023 UNIMA Council held in Bali (April 26-30), with its attendant international seminar and festival, a six-day Wayang Workshop (May 2-7) endorsed by UNIMA-USA expanded fifteen international theatre practitioners’ appreciation of Balinese wayang kulit, classical dance, and topeng masking, clarifying the interlocked aesthetics and essences of these Balinese arts. The mostly American participants were joined by puppeteers from France, Iran, Argentina, and South Korea. All but three of the participants had had no previous study of Balinese wayang kulit.

The Six-Day Wayang Workshop

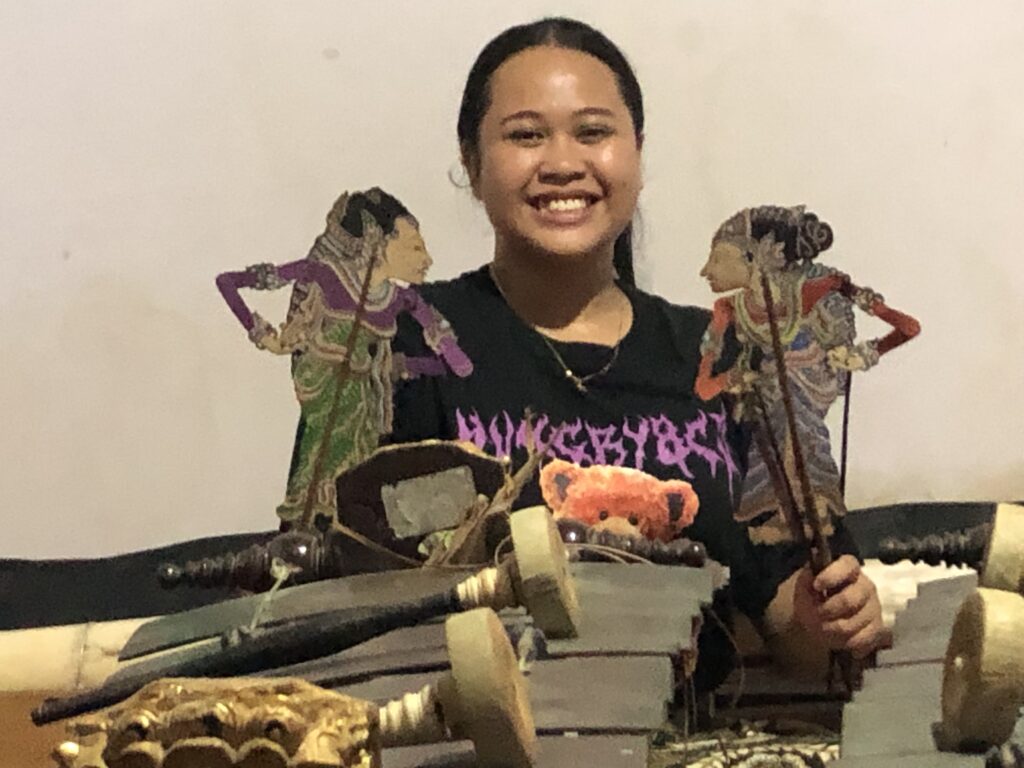

The instruction for the workshop was developed by I Nyoman Sedana, professor of pedalangan (wayang puppetry) at the Institut Seni Indonesia (ISI, Indonesian Institute of the Arts), Denpasar, and director of Balimodule, and his talented twenty-five-year-old son, I Made Georgiana Triwinadi (known as Georgian), a recent ISI graduate. American dalang Kathy Foley ensured there was a focus on the basics, with repetitions and simplifications of dance sequences and dialogue given the limited time frame and the great complexity of the art. Workshop participants rose to the challenge of this heady experience.

The introductory training in wayang kulit from the perspective of the dalang (puppet master) that the workshop participants received focused on the specific manner in which a wayang character moves, thinks, speaks, behaves—essentially, how the character expresses its intrinsic nature through its body, face, and inner being. Via trying out each character or scene of walking, fighting, or wooing with one’s own body, face, mind, and empathetic understanding of each individual character, participants got a “danced understanding” of the art form; lessons could then be transferred to the inanimate figures, the wayang, giving the scenes life.

The workshop began with specific movements of four major types of wayang characters. This approach was unexpected; participants might have assumed they would work directly with the puppets and “learn” how to animate them against the cloth screen. However, this embodied approach made it apparent that the puppets were indeed dancing and the students needed to know the dance of each wayang character type to later transfer to their right or left hand (Figure 1). The four character types were: 1. refined (alus) male, for example, Rama or Arjuna; 2. refined (alus) female, for example, Rama’s wife Sita or Arjuna’s wife Subadra; 3. rough/crude (kasar) and demonic characters, such as the demon King Rahwana; 4. mythical creatures that, while “wild,” are noble, such as Hanuman (the white monkey and Rama’s general) and Garuda Jatayu (a noble bird), or the more ferocious nagas (snakes or dragon-like mythical beings).

I had previous experience in Jakarta studying wayang kulit purwa in the Central Javanese Surakarta style. From my very first lesson, I was seated facing the white cloth screen (kelir), with the wayang in hand, and taught how each character was to enter the playing space, how the wayang would need to be placed on the kelir, and how to plant the wayang in the banana trunk (gebog), etc. In contrast, this study began with my own body—an effective methodology forcing me to move, think, and “become” the character types demonstrated.

Workshop participants first practiced basic movements and corresponding head positions and expressions of the four basic character types. Then, with wayang figures in hand, each workshop participant applied those gestures, practicing with the puppets on a section of studio wall.

Georgian was the principal demonstrator of the wayang figures on the kelir. First, he would demonstrate how to place the wayang—with the nose of the puppet’s face pressed against the screen while the base of the figure does not quite touch the bottom edge of the screen—so its shadow would be thrown with the light of the lamp (damar), producing a “life-like” effect. Like the human dancer, the puppet figures were to “glide” and “flow,” but on a screen. Pak (Mr.) Sedana accompanied demonstrations by playing the gender (bronze metallophones, percussive instruments that provide the background music for a wayang performance). We saw how to move the figure from one position to another by keeping the nose of the wayang firmly on the screen, turning it in a “figure 8” pattern.

An example of a characteristic movement of the refined (alus) male character, such as Arjuna, is the elegant extension of “his” arm across the screen. In enacting the gesture of obeisance (sembah), a greeting representing respect and reverence, the alus male will bow and touch his head and then his forehead with the arm facing the one being respected, just as a refined male would greet a king in the courts of Bali in times past. Both alus male and female characters would move with an elegant swaying motion; the refined female, in particular, the epitome of lovely womanhood (Figure 2).

To animate Balinese shadow figures aesthetically then is to, first, learn the postures and movements of each character type. These include the specific style of foot work for each character. The highly refined or alus characters’ feet are represented in the kulit figures and by wayang wong dancers alike as elegantly close together. In contrast, the aggressive or kasar characters’ feet are spread apart, with the most bellicose and malevolent of characters with their legs widely and aggressively opened. Similarly, the position of each character’s arms, whether held at a high, mid or low level, defines type. The face and indeed the expressiveness of each character type, delineated through prescribed rules in the carving and coloring of the figure, are brought to life on stage through motion and voice by the dalang. The pitch and quality of voice of each character type are also very specific: indeed, the way in which the dalang modulates the voice of each character—whether high-pitched and sweet, heroic medium-high pitched, whining, cajoling, rough, brutal, demonic, and many voices in between—are indicative of specific characters, recognized by wayang’s aficionados and the general public. These movements and sounds are fundamental to creating each specific character within each specific moment of the play. The dance-like movements and vocal timbre of characters, once absorbed by the workshop participants, were applied to the wayang figures.

Each day began with mixed morning exercises held at Pak Sedana’s home studio and introduced basic elements. For example, on day two of the workshop, hand-to-hand combat between dancers was first demonstrated, then “reproduced” by the workshop participants, who tried out the fighting moves, first singly then in pairs. Weapons were added to the fights. Once the participants “got the hang of it,” the stylized battle movements of the wayang figures were then demonstrated by Georgian on the screen, for example with two wayang characters driving chariots, then hopping off their vehicles to do battle with their identifying weaponry and fighting styles. The workshop participants then practiced the basic battle movements, but without the screen, each holding two wayang figures, one an alus character in their right hand, the second, a kasar character, in their left.

The group advanced in knowledge over the week, learning first general movement, then drum syllables that accompanied the walk or gesture, and the vocal timbre for each character type. We progressed from greetings to the hits and shouts of battle scenes or cuddling and cooing of love interludes.

Morning movement and puppet exercises were followed by afternoon field trips to experience more of Bali’s distinctively rich culture. Visits included participation in a seminar held at Institut Seni Indonesia-Denpasar (ISI, Indonesian Institute of the Arts), meetings with local dalangs, topeng (mask) performers, and attendance at two temple ceremonies.

The afternoon session on the first day was spent at the Indonesian institute of the arts, ISI Denpasar. The seminar presentations from ISI staff and PhD students included papers on the following topics: Bhatara Kala (the Indonesian ancient God representing Time), a sacred myth represented in wayang theatre; the significance of the dalang in wayang kulit; how wayang has been employed to spread the word among the community about COVID-19 prevention; and other topics. International workshop participants also presented. Salma Mohseni Ardehali, Visiting Lecturer at Tehran University of Art, spoke on Iranian forms of animism and how these are represented via objects, such as flags and figurative elements. Her paper showed that the tendency toward vibrant objects in Iran may have preceded the arrival of Islam and has persisted in the region. Korean puppeteer Daejin Eum, who trained in the namsadang tradition (popular arts which include puppetry) and is the director of the yeonhui (performance combining traditional music, dance, and singing) group Eumma, shared his insights into contemporary Korean puppetry, showing how he updates the traditional namsadang with puppets doing feats of spinning disks or playing drums. This form, like the Iranian example, has roots in shamanic performance. Patricia Hardwick, who teaches at the University of Education Sultan Idris (UPSI) in Malaysia, talked of the Indonesian-Malay mak yong theatre that was once performed with masks. Matthew Isaac Cohen spoke of his recent production based on the Ramayana, A Tale of Trees and Wood, with an ecological slant. Bowling Green State professor Bradford Clark talked of designing a Shakespeare version of The Tempest in the 1980s that was inspired by Balinese masks and his more recent Baron Munchausen (2022) production, with marionettes. Dmitri Carter gave insights into his work with the Seattle-based Northwest Puppet Centre and its recent exhibits in Taiwan. Due to the international composition of the group, the topics were diverse. Several of the Balinese presentations appear in this volume of Puppetry International Research.

Another day’s trip took us to the village of Bona, in Gianyar Regency, to the home of nonagenarian master dalang, I Made Sidja; his sons include Dalang I Made Sidia. One of Dalang Sidja’s other sons, a very young grandchild, and Sidja himself demonstrated wayang kulit (Figure 3). Another stop was in Sukawati at the home-studio of another senior dalang, I Wayan Nartha, one of the best wayang makers since the 1970s, and his son, I Ketut Sudiana (who is also a teacher of pedalangan at ISI Denpasar). At the sanggar, the allied arts of wayang performance (pedalangan), music (karawitan) and the making of the wayang figures are taught. As an example of wayang kontemporer (contemporary puppetry), I Ketut Sudiana created a new form of wayang beber: a scroll backdrop that was more than ten meters in length, illustrating, in multiple repeats (made by way of a huge inkjet printer), battle scenes from the Mahabharata. Oversized kulit figures enacted the chosen drama for this production, which he created for his PhD production.

The next trip was to woman dalang, Ni Sendy (winner in a recent competition of women dalangs) (Figure 4). Two young women were playing a musical piece in the haunting gamelan selunding style (selunding, meaning “great” or “large”); this sacred and rare ensemble of Balinese gamelan music is from Tenganan, a village in east Bali. Ni Sendy performed a short scene from the wayang kulit repertoire, accompanied by two women gender players. This was followed by an all-women gamelan semar pegulingan ensemble, a particularly sweet toned orchestra, which was played for the workshop group.

The workshop participants also saw performances, including a topeng at a temple festival nearby and some trance dances outside of Denpasar. One morning we donned traditional Balinese dress to visit the temple of the Pande (the metalworker community) to attend a special ceremony which included topeng mask dance by acclaimed dancer I Ketut Kodi and his son. In essence, akin to Balinese wayang kulit, Balinese topeng is a dramatic dance form in which one or more ornately costumed performers wearing masks, and accompanied by the gamelan, interpret traditional narratives concerning fabled noble ancestors’ myths. The traditional masks performed that day included topeng manis (a refined alus hero), topeng kras (a warrior, an authoritarian character), topeng tua (an old man who jokes and interacts with the audience), topeng jauk (the dancer wears the mask of a demon and gloves with long nails), topeng sibakan (a joker in a comical half mask), and topeng Sidakarya (Figure 5), a sacred mask representing an old man with bucked teeth whose name means “complete the ceremony.” Sidakarya is needed at Balinese Hindu rituals to finish the ceremony.

The workshop participants could appreciate how these character types are expressed through dance, costume, and mask and could then compare them to the wayang kulit figures we were introduced to, which reflect nuanced character through the art of the carver-painter and the mastery of the dalang.

Another temple event we attended was the full moon ceremony at the Bona temple complex. Seated outdoors, the local men’s kecak group chanted interlocking calls, along with a female choral group, while dancers performed the abduction of Lady Sita from the Ramayana. The evening’s ceremony included two trance style dances—by two prepubescent females (sanghyang dedari) and two horse-riding adult male dancers (sanghyang jaran).

The two young girls, in trance, were carried onto the performing space and performed in delicate unison while seeming in a semi-somnambulate state. This was followed by the energetic fire walking of the sanghyang jaran horse dancers, moving and swirling through a fire of coconut husks, while each riding a symbolic horse. The two male dancers, like the young girls, eventually collapsed and were revived by holy water. Thus, besides experiencing a Balinese temple ceremony, the workshop participants could see how these character types—refined female and fiery male—are expressed through dance, which the wayang kulit figures approximate through expressive carving and the animating mastery of the dalang.

For the finale, the workshop participants put into practice some of the elements of wayang kulit they had absorbed. Pak Sedana suggested the play (lakon), Arjuna’s Meditation (Arjuna Wiwaha) as a scenario. The workshop participants practiced with the oversized puppets (created by Georgian and his wayang group) at the community hall (banjar) across the street from Pak Sedana’s home-studio. Georgian demonstrated moves whilst holding the giant wayang figures. Then participants manipulated the four-foot or more figures: the demon king Niwatakawaca with his demon army, the scene of the seductive heavenly damsels (bidadari), and the five giant “tree of life” (kayonan) puppets. Work on the vocal elements included the “songs” or mouth music, such as the demon army’s “chuck chuck boon – chuck chuck sidh”, “deet bong – deet seer” and “tu-tu gah, tu-tu gah, tu gah” chants; and a short tune associated with the refined female characters: “seeriyaah – arriyaah – luuriyaah – seeriyaah.” (Note: the above written “notation” is my version based on an oral-aural learning technique and no doubt others may have sung slightly different syllables.) To end the piece, Pak Sedana had composed a closing song, which began with: “Please forgive us for any inconvenience…,” to ask the audience to excuse the performers for any shortcomings. Two children of workshop participants wearing monkey masks joined in the forest scene replete with masked and puppet animals. The giant wayang figures of Barong (a lion-like protector) and Rangda (a demonic manifestation of the Goddess Durga) were to epitomize positive versus demonic in the drama; selected workshop members practiced with the extra-large, multi-hinged figures (Figure 6). Matthew Isaac Cohen (an American dalang) animated the small kulit figures on the shadow screen, including the comic characters Twalen and Merdah (assistants of the protagonists) and Delem and Sangut (the antagonists’ comic sidekicks).

The forty-minute performance on the last evening of the workshop drew local children, their parents, several dignitaries, and a dog (the last-mentioned joined the performers onstage). The workshop participants created a funky, energetic, decidedly rough around the edges, show (Figure 7). The six-day Wayang Workshop was deemed a great success—enjoyed by all, including the dog.

Assessment

1. Much of the workshop revolved around the characteristics of types: 1) heroic male characters, 2) refined female characters, 3) demonic characters, 4) special characters.

2. The workshop began with the typical dance movements associated with these character types. As a whole, the participants seemed to resonate most with the demonic characters.

3. The sessions covered the typical voices. Perhaps the short “call and response” exercise that focused on a variety of laughing styles proved the most satisfying as lead by Dalang I Made Sidia who guest-taught one day.

4. The introduction of the syllables for expressing music was great fun. Pak Sedana introduced short verbal chants which reflected the percussive sounds or lyrical passages associated with the character types.

5. We learned the moves, or group interactions, breaking into pairs, of the right-hand (alus, protagonist) and left-hand (usually kasar antagonist) figures, first by doing one puppet’s moves physically, then seeing how these moves were duplicated with two puppets moved by one animator.

6. The performance was a fitting capstone with movement, voices, and musical chants of the demonic characters and heavenly goddesses as the opposing “choruses” testing the hero Arjuna who only appeared on the small screen. The workshop gave us all a taste of the range of Balinese wayang, from the funky demonic to the heavenly divine.

Karen Smith

President, UNIMA International