Balinese see puppetry as the model and source of dance drama. A dalang (puppeteer) responds flexibly to the change from puppet, to masking, to human dancers and suits the needs of those seeking his/her expertise. To revive tourism, which had fallen due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the 2022 Sanur Village Festival (Sanfes) took the theme Surya Sewana (Glorifying the Sun). As a dalang, the author I Made Sidia, created a wayang wong (literally,“human puppetry”) performance staged at the festival telling the Ramayana story of the hermit Resi Wiswamitra, Rama, and Lakshmana carrying out the Surya Sewana ceremony to neutralize catastrophe. This innovative wayang wong was performed by young Balinese actors/dancers and accompanied by hybrid music (gamelan, keyboard, and bass), using digital technology and other innovations. The performance glorified the sun, rising above pandemic challenges as both a purification effort and a pragmatic attempt to renew Balinese tourism.

I Made Sidia is an award winning Balinese dalang who studied puppetry and dance from youth as well as earning his degree in puppetry at STSI (now ISI [Insitut Seni Indonesia, Indonesian Institute of the Arts]). He has been teaching at ISI since 1993. In 2000, along with his father Maestro Dalang I Made Sidja, he founded the Paripurna Art Company in Bona, Gianyar, Bali, and his large-scale dance drama works are seen in many festivals. He has undertaken multiple cross-cultural collaborations and tours internationally. He is currently a PhD candidate in wayang puppetry at ISI Denpasar.

Introduction

As a dalang (puppeteer/dance drama narrator), choreographer, and exponent of modern Balinese theatre, I try to achieve what padalangan (art of the puppet master) demands: response to the present with attention to Balinese heritage while keeping audiences engaged. In this paper I will: 1) explain how dance drama fits under the rubric of puppetry/material theatre, 2) discuss how the tourist economy and Balinese culture have collaborated since the 1970s to build the arts and the economy simultaneously, and 3) give a case study of a wayang wong (dance drama; literally, “human puppetry”) presented at the Sanur Festival 2022 as Bali emerged from the COVID-19 pandemic (Figure 1).

Padalangan and Dance Drama

In the West, the arts of theatre, music, dance, and puppetry are often seen as discrete and playing to different audiences, with puppetry often seen as a so-called “minor” art targeted at young viewers. The arts of Bali, by contrast, combine all the above arts in one production. Audiences are of all ages and puppetry/masking is envisioned as the fundamental art from which the other “newer” genres are generated. The premier artist is the solo puppeteer, who manipulates all the puppets in wayang kulit (shadow puppetry), or dances multiple masks in the related solo mask form topeng pajegan. The dalang combines all arts in one performance (singing, dancing, and acting), and, therefore, when a group wants to create a new multi-person theatre piece, they understandably turn to a puppet master to lead. The dalang has a knowledge of the ritual practices, narratives, characters, music, and dance sequences needed. Thus, he (or today sometimes she) can weave the many dancers and musicians together to create what in one form is called “human puppetry” (wayang wong) or in another, the dance drama sendratari (from seni [art], drama, tari [dance]). The dalang shows the way, but instead of playing all the roles, he uses the dancer-actors as his wayang/puppets. In both human actor forms the dalang determines the progress of the story, but in wayang wong the actors speak their own lines, while in sendratari, dialogue is superfluous and actors merely mime the action. In each of these genres, movement, costumes, and storytelling remain close to the puppet models. Therefore, what I as a child learned to do with puppets under the instruction of my father, Dalang I Made Sidja, I apply in the wayang wong productions with a hundred or more performers from my studio, Sanggar Paripurna.[1]

Wayang Parwa to Wayang Wong: Puppets to People

Thus, wayang wong is wayang (puppetry) enacted by people. It is thought to have originally developed as barong belas-belasan (performances with masks, each animated by an individual dancer) or barong kedingkling (itinerant masking performance) as groups of dancers would go from door to door during Galungan and Kuningan (holy days that occur every six months in the Balinese calendar). These performances were done to expel evil and attract beneficial spiritual energy. Groups of mask performers would dance a few minutes in the front of each house compound and be given a few coins in return. The precise dates of developing more elaborate dance dramas is unclear, but scholars feel it was associated with court entertainments in both Java and Bali. Soedarsono, writing in 1984, saw it as a form of entertainment originated in the Majapahit kingdom in East Java, beginning in the fourteenth century and which is given varied names in court records (wayang wwang, raket, tekes); he sees contemporary Balinese wayang wong as a continuation of East Java’s wayang wwang (which again means “human puppetry”) and says it was established by Javanized Hindus in Bali (Soedarsono 1984, 12). Current Javanese wayang wong in Central Java, by contrast, develops later and only traces its roots to 1755 as an innovation of the Yogyakarta Sultan Hamengkubuwana I (pp. 15-17).

Wayang wong, as performed in contemporary Bali, is credited to Dalem Gede Kusamba (r. 1772-1825), ruler of Klungkung: “He stipulated that the repertoire for the new genre be taken from the Ramayana, and he directed that the dancers create a wayang wong, that is a dance based on the wayang (shadow puppet) theatre using men in place of puppets” (Bandem and deBoer 1995, 59).[2]

The most complete wayang wong performancesin contemporary Bali are that of Tejakula, Buleleng Province, and Wayang Wong Taman Pule temple at Mas Village near Ubud in Gianyar. Both these wayang wong performances are presented for the odalan (temple festivals)with the first day’s show primarily given for the gods and the second day’s performance meant for human audiences. At Tejakula, the form features the story of the death of Prahasta (a minister of Rahwana) for the first day, and depicts the slaying of Rahwana’s giant sibling, Kumbakarna (p. 66), on day two. At Taman Pule temple there is a complete sequence of Lady Sita’s abduction by the demon King Rahwana. Characters wear large masks in the Tejakula version and somewhat smaller masks in Taman Pule, with the visages emulating the iconography of the wayang kulit characters. The persistence of masks in the wayang wong makes sense, in that the Ramayana stories feature many monkeys, eagles, ogres, and grotesquely visaged clowns. This contrasts with the Mahabharata, Panji, or otherstories, where a greater number of characters, however rough, are human. Masks allowed the animal and demon cast to be well represented, even if the masks diminished the audience’s ability to hear clearly the dialogue actors speak. The dalang-like function of making sure viewers understand the story was largely done by the panasar (clowns): Twalen (also Tualan) and his son Merdah (also Werdah) serve the forces associated with the hero Rama, while Delem (Figure 2) and his sidekick Sangut serve the forces of Rahwana, the antagonist of the epic. The clown-servant faces are modeled on four clowns of the same names of the shadow puppet theatre. For all the characters, costume, the body shape of the performer cast for a role, props, etc., are related to the precedents in the puppet theatre. Ritual similar to that used in shadow theatre is also involved. Bandem and deBoer (pp. 67-68) discuss how offerings are required and masks are sprinkled with holy water before being distributed to performers. During a performance, headdresses (gelung) and masks (tapel) hang from a tree near the outdoor performance space as the dancers watch the action and await their entrances. The performers’ stylized gestures give a puppet-like impression to their dancing, fighting, and other actions.

Everything in this art has been affected by the aesthetics of puppet theatre.

The shadow theatre provided a number of elements to the wayang wong. Certain aspects of the dancing, particularly the hand gestures, specifically imitate the movements of the shadow puppets on the lighted screen. The music of the wayang wong also came from the puppet theatre; accompaniment is provided by the gamelan batel (Bandem and deBoer 1995, 66).[3]

The puppet theatre gives more time to dialogue and narration, whereas in the wayang wong the dance element expanded.

Wayang wong masks of demons, monkeys, and clowns are still widely sold to tourists, but in recent years one tends to see Ramayana stories not in wayang wong,but mostly in reduced versions where the dialogue of traditional wayang wong has been cut and the movement has been adjusted toward sendratari,which rarely attempts to depict a complex story. This recent tendency contrasts with traditional village presentations of wayang wong at Tejakula or Mas, which maintain dialogue in archaic language, and, for this reason, proves “difficult” and fails to attract younger audiences who do not understand the language and find it “too slow.” I have replaced masks in my performances outside these villages for many characters with make-up. While minimally maintained in the two villages, the form has been in danger of lapsing.

Institut Seni Indonesia authors, Ruastiti, Sudirga, and Yudarta, have written articles espousing a revival (2019, 2020, 2021). They discuss the creation of a new wayang wong in Balinese dance style that used the Ramayana story of Cupu Manik Astagina (Eight-sided Diamond Case) that I developed. The tale shares how some of the major figures of the Ramayana first became monkeys through foolish actions and family feuding. This tale of Resi Ghotama, his wife (Dewi Indradi), and their three children (Dewi Anjani, Arya Bang/Subali, and Arya Kuning/Sugriwa) used digital technology and involved young Balinese players of Gianyar Plenary Art Studio performing for a ceremony for the Pura Dalem Temple (Shiva/Siwa and cremation temple) in the local village. This performance, with its narrative about how youngsters—too impressed with material things—literally make monkeys of themselves, drew young audiences back to wayang wong. Viewers saw this ancestral art could be important in teaching life values. This experimental production, using digital media and projections, elaborate lighting, and other features, was deemed successful, having the potential to draw tourist attention at the same time as it strengthened Hindu ethics among the young.

The development of an innovative wayang wong model with digital technology that includes millennials should be continued. Besides, as an effort to socialize educational values for future generations, this wayang wong innovation is also a vehicle for the preservation of the nation’s cultural arts (Ruastiti, Sudirga, and Yudarta 2021: 97).

My reading on wayang wong and knowledge of attempts at the revitalization of kindred traditions on Java, as well as my work with Ruastiti, Sudirga, and Yudarta on Balinese projects, helped me as choreographer-director think about how to create an innovative wayang wong with my own company for the Sanur Village Festival 2022. I wanted to continue both revitalizing contemporary wayang wong performances in Bali and to help with the recovery from the crisis that COVID-19 had created in the Balinese economy. To understand why this performance was commissioned, it is important to know the place of tourism in Bali. Arts and culture articulate with cultural and economic success.

The Arts in Cultural Tourism

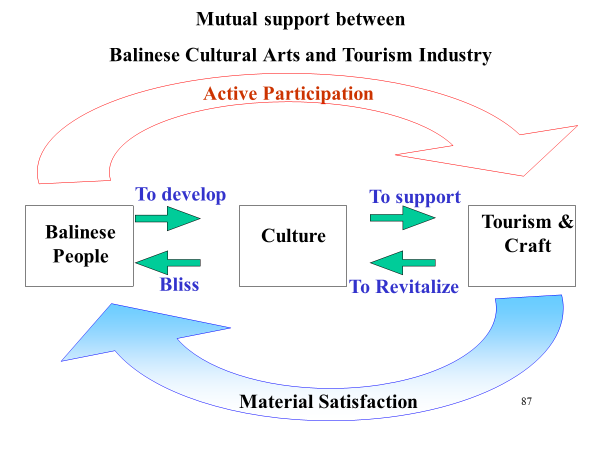

The Balinese realize that performances and heritage are their major cultural capital. Performing arts promote the sustainability of cultural tourism (Bali Provincial Regulation No. 5 [2020]) and contribute heavily to the economy—estimated at 60-70% of the GDP.[4] Since the 1970s, Bali has sought to leverage its arts for promoting cultural and economic viability. As GDP has grown, this emphasis on cultural tourism has actually had the effect, not of destroying, but in some ways enhancing the quality of the performing arts (see Figure 3). Resources gained from tourist dollars are often reinvested in ceremonial as well as more secular events.[5] Performances in temple festivals and local contexts have grown in size and artistry. Gatherings—like the annual Bali Arts Festival, which was first thought of as a lure for tourists—have proved successful in encouraging groups from all over the island to compete in contests and advance artistically. With the festival’s spectacular performances and many competitions (i.e., of child puppeteers, gender wayang players [puppetry music], wayang-style painters, mask makers, etc.), the event promotes the continued training of the next generation in important arts that might otherwise fade (Sumandhi and Foley 1994). While the Bali Arts Festival does draw tourists, most of the audience is Balinese. Groups come to support their children, grandchildren, and the event builds local pride. What youth and adult sports in a Western context may contribute in drawing local enthusiasm, the arts festival encourages in its gamelan, dance, and art competitions.

The vision of Governor Ida Bagus Mantra (1928-1995), in office from 1978-1988, was important in promoting the Balinese “cultural” approach to development. Mantra (1996) felt tourism could be leveraged to strengthen Balinese religious and cultural life. Aesthetics rising from Balinese Hinduism embrace the performing arts and Mantra thought support for the arts would encourage humans to progress both philosophically and economically. Since his governorship, Bali has held to Mantra’s idea: tourism can help stimulate cultural life, providing many opportunities to present artistic work. Prosperity provides resources for creative work and entrepreneurship, which is then recycled for temple festivals, rites of passage, and other ceremonies that require the arts. Thus, cultural capital and entrepreneurship grow as the Balinese community strengthens the Balinese tradition itself.

However, the COVID-19 pandemic had a negative impact throughout the tourism sector, as well as the creative economy (Sugihamretha 2020). The Central Bureau of Statistics noted that foreign tourist visits to Indonesia in January 2020 fell quickly compared to the December 2019 arrival of 1.37 million. By April 2020, only 273 tourists arrived at Bali’s Ngurah Rai Airport for the whole month as compared with 476,104 in April a year before, down 99.94%; and in May, only thirty-four tourists came (Ruastiti, Sudirga, and Yudarta 2021: 27). Balinese travel services, restaurants, and hotels were forced to go out of business. In 2020, only about 10-30% of Bali’s tourism businesses were thought to be able to survive (Sutawa 2020).

As the pandemic eased in 2022, traditional Balinese arts were again seen as part of reviving Bali’s tourism business. The Sanur Village Festival (Safes), described as “a joyous gathering of community, food, music, entertainment and village culture,” was revived, and, “After two years of COVID shutdowns, the return of the festival marked the beginning of better times in Bali, and had the village out to party and celebrate Sanur, thriving once more” (Srdarov and Widayati 2022). The festival, usually held annually, had been suspended due to the pandemic. Sanfes 2022 took Surya Sewana (Glorifying the Sun) from the Ramayana epic as its theme and presented a wayang wong with a story about a ceremony centered around the energy of the sun god, Surya.[6] The work was commissioned from Sanggar Paripurna and involved 135 performers, including some puppets and digital projections, elaborate costumes and some masks, and a plot appropriate to the event. It was presented at Matahari Terbit Beach, Sanur, Denpasar on 21 August 2022.

Wayang Wong Surya Sewana was an innovative production, meant to appeal to youth who are today often “held hostage” by various modern online media, forgetting traditional culture. Our millennial wayang wong was created by implementing aesthetic concepts and artistic methods I learned from my father: 1) composing a story with a contemporary touch via references to an epidemic; 2) developing an appealing plot of the youthful heroes Rama and his brother Lakshmana working in concert with a holy man to remedy disease caused by the ogre king Rahwana; 3) refining characterizations by complex rehearsals; and 4) using stage technology in line with the current developments of IT—digital projections and strong lighting helped give scenic nuance and enlivened the stage. Innovations in choreography, dialogue, and musical accompaniment and other features can give traditional forms like wayang wong renewed life, as the ongoing research of Ruastiti, Sudirga, and Yudarta clarifies (2019, 2020, and 2021).[7]

Surya Sewana describes the ceremony of worship of the sun god Surya who delivers, to Rama and the hermit-priests who have been endangered, warmth and harmony for life in the world (Figure 3). The tale was metaphorically appropriate and pragmatically intended to help revive the life of Bali’s tourist sector post COVID. It was specifically designed for performance at Sanur, an essential tourist locale, which, due to the downturn in tourism, was much in need of warmth and harmony.

As I developed the piece, I thought about ways to make story, setting, costume, music, and choreography compelling (see Table 1).

Table 1. Innovation in the Traditional Balinese Wayang Wong Show Surya Sewana

| Aspect | Information |

| Story | The story chosen, namely Surya Sewana, is a wayang play related to Resi Wiswamitra with Rama and Lakshmana who held the Surya Sewana ceremony to avoid disasters instigated by the demonic forces, including the giants Marica, Tataka, Sunda, etc. who serve King Rahwana (here, collectively the demons represented COVID-19) as Rama, avatar of the preserver god Wisnu/Vishnu, restored harmony to the universe. |

| Setting | Setting and artistic LCD lighting background projected on the screen are used, including visualization of scenes in forest hermitages. Stage set-pieces in front of the screen included accessories for trees, flowers, butterflies, etc., unlike traditional wayang wong, whichhas no set pieces. |

| Costume, Mask, Puppet | Innovative costumes, such as the monkey (wanara) costumes in bright colors, were worn by wayang wong actors. Masks were used for clowns who also appeared in puppet form using traditional wayang kulit leather puppets. |

| Dialogue | Dialogue uses three languages—Balinese, Indonesian, and English. |

| Music | Traditional Balinese wayang music/gamelan combined with digital music composition (keyboard and bass). |

| Choreography | Choreography accentuates movements that are agile, dynamic. |

As listed in the table above, the innovation of our Surya Sewana included several aspects. First, the wayang story needed to fit into the current era and reach the young Balinese. Surya Sewana from the Ramayana epic tells of the sage Resi Wiswamitra who solicits the help of the youthful Sri Rama and his brother Lakshmana. Together the three hold a Surya Sewana ceremony to the sun god to avert disaster and restore harmony. The catastrophe we were referring to as we rehearsed was, of course, the COVID-19 pandemic. In the plot, we showed the outbreak of disease in the community was the work of Rahwana, the demon king of Alengka. His troops were spreading this disaster. In my analysis through the Surya Sewana ceremony, Resi Wiswamitra, along with Sri Rama and Lakshmana, fight the threat of Rahwana, and restore peace to life. This is what we as artists were doing at Sanfes—returning our community to physical, economic, and spiritual balance.

We attended to the story setting. We began with the scene at the hermitage where Resi Wiswamitra, along with Sri Rama and Lakshmana, prepare for the ceremony. The second scene showed the actual ceremony in the forest, warding off disaster and neutralizing the outbreak of disease. A fierce battle took place between Sri Rama’s troops and those of King Rahwana. The third scene, still in the forest, showed the condition of the universe returning to normal.

In the complex and artistically pleasing stage setting, trees, flowers, and butterflies appeared. Colorful LCD lighting and visualizations that supported each scene were used. Wayang wong in general can be staged either indoors or outside and current performances are supported by complex stage technology, including light reflectors and so on (Fig 5). For this performance we played outdoors with projections of a palace, hermitage temple (puri), and forest as backdrops, creating a lively atmosphere. Experts in the IT field are part of our team and our professional management, including tightly-scheduled stage adjustments with lighting cues and sound modulations which set the scene. This kept viewers’ attention for the three-hour duration of our show. LED lights as backdrop helped to transform the visuals on the screen from forest to village and palace to ocean. Viewers watched avidly until the end as they listened to the music provided by a semarandhana orchestra. [8]

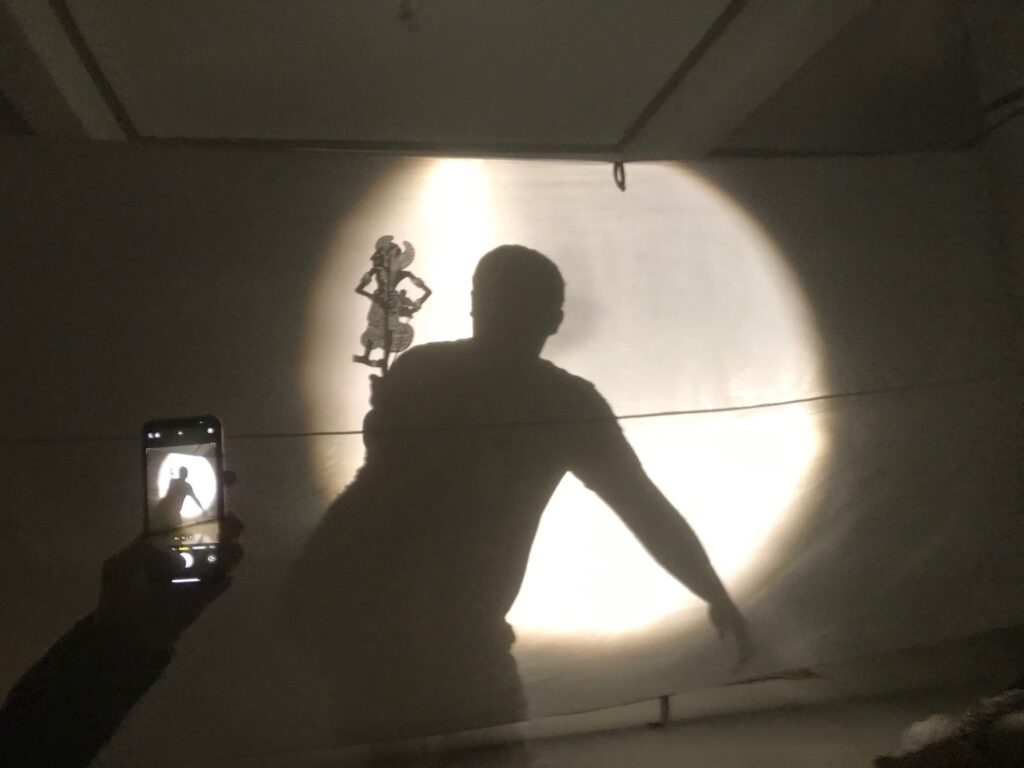

Make-up and costumes were innovative. This wayang wong performance combined characters from wayang kulit (shadow puppetry) and wayang wong (human puppetry). Some characters, like the clowns of the right (Twalen and Merdah) and the left forces (Sangut and Delem,) wore masks when they appeared as onstage figures. They also sometimes appeared as shadows figures projected behind the onstage dancers. Characters like Rama, Lakshmana, and the hermit-priest Wiswamitra were barefaced. This combination helped tourists (as well as Balinese youth not versed in wayang wong understand the equivalency between unmasked, masked, and puppet characters. Seeing the forms combined in one production, with the clown servants sometimes puppets but then masked characters, helped Balinese audiences and tourists see the relation of these genres. This also allowed us to play with scale—a large puppet of Twalen, for example, could loom over the small humans in front of the screen as the clown commented on what was happening in a scene.

Experimental wayang mixing puppets and dancers began from the 1990s. My father, among others, was involved in a production of Larry Reed in San Francisco. I myself collaborated with Reed on a production in New York and later worked extensively with Peter Wilson, an innovative Australian puppeteer, on the Ramayana-based intercultural experiment, Theft of Sita, which played at the Adelaide Festival in Australia in 2000 before touring internationally. That show dealt with ecological themes using elaborate lighting and projections and, like my Sanfes production in 2022, was sometimes performed outside under a starry sky. My international experiences have allowed me to further explore shadow casting and projections that I have used in subsequent productions (see Laurie 2000 for discussion of Theft of Sita).

Gamelan players are essential to preserve the traditional heritage. In my productions, they collaborate with MIDI music and Western instruments to create engaging musical compositions. I always use wayang models as a place from which to start. The basic music was provided by a regular gamelan semarandhana orchestra, but we combined it with digital music, keyboard, and electric bass. This made the sound contemporary and appealed to our young audiences.

We did not use masks for most characters, just make-up. Our audiences like to see faces: and so, we worked to make performers’ make-up thin yet effective in the bright lighting. Costumes with headdresses (gelung) drawn from the puppet/mask theatre models made the main characters immediately recognizable. Yet we worked for greater elegance in the costuming than in traditional wayang wong; for example, we gave special attention to the colorful representation of monkeys (wanara) that assist Rama in defeating demons.

We made innovations in dialogue using three languages: Balinese, Indonesian, and English. Balinese and Indonesian were the main languages, while English was used sparingly; but cursing in three languages (including English) could create comedy for locals, and foreign tourists could fully follow the emotion presented.

Finally, we included choreographic innovation. Our choreography felt dynamic because our dancers are fully trained to understand how to interact with the technology we use. They move to and fully exploit the possibilities of the sophisticated, colorful lighting design and this makes the wayang players’ movements feel more agile. Millennials whose life is steeped in technology respond to wayang wong performers who know how to interact well with sound systems, LCDs, and our laser technology. As a choreographer, I help dancers understand that technology is their friend. The latest IT is also used for our broadcast productions and then we prepare CDs. Our videos are played on TV and we upload to YouTube. Up-to-date IT is in demand.[9] Today’s information and communication technology are at the core of every aspect of the creative process that is carried out by contemporary artists (Budiman 2019).

We sought to inspire youth to appreciate wayang wong so as to perpetuate the tradition. We were successful. Many of the 135 performers of Surya Sewana were young Balinese. We actively cultivated youthful participants, as players, dancers in group choreographies, make-up technicians, and other support crew. Involvement in wayang wong from a young age cultivates passing the art from one generation to the next. Young Balinese are the inheritors who will determine the sustainability of wayang wong in the future.

The audience response was enthusiastic, including that of the tourists. Praise came not only from the older generation, many of whom have long been fanatical spectators of wayang wong, but also young Balinese. The research of Ruastiti, Sudirga, and Yudarta (2020) confirms the interest of young Balinese in performing and watching this revitalized wayang wong, and their enthusiasm assures us the noble teachings of wayang will be passed from one generation to the next. As proposed in the theory of social action (Bourdieu 1990), through performing and watching wayang wong young Balinese build their mental structure (habitus) to carry forward this art.

And of course, as evidenced by Ruastiti, Sudirga, and Yudarta (2021), staging innovative wayang wong is able to attract tourists too, helping outsiders understand how Balinese value these old religious stories as a template for facing the challenges of our time. In the current era of globalization, local culture can rise, color national culture, and even influence global culture (Collier 1994, 53-61). Local traditions of art and culture, including wayang wong, have a great opportunity to impact cultural identity. In developing this production, we aspired to reaffirm and share Balinese ideas for ourselves, the nation, and the world.

Wayang has persisted as an important performing art because of its teachings. For example, the tree-of-life/mountain image that opens the shadow puppet show is meant to symbolize what all living things desire: safety, happiness, prosperity, justice, and peace. It represents the world and all its contents: mountains, seas, plants, animals, and humans (Darmoatmojo 1989, Foley and Smith 2015). Wayang communicates important religious values (Soeprapto 2009). Wayang cultivates sensitivity, sensibility, ethics, democratization, and educates us on how to live in an atmosphere of pluralism.

The Meaning of the Surya Sewana Performance

Surya Sewana’s story was one of purification and neutralizing negative influences, including the COVID-19 outbreak which, in our own times, has claimed many lives. We chose the theme of the Surya Sewana ceremony as a ruwatan (purification) for the universe. Ruwat in Balinese wayang aims to neutralize negative forces in both the Bhuana Agung (“Great World”/cosmos) and Bhuana Alit (“small world”/individual human). Through the Surya Sewana ceremony played on stage, metaphorically, the deadly COVID-19 epidemic was neutralized, so that human life could return to normal.

The story of Surya Sewana was about the “harmonizing the universe” by respecting the lifegiving sun in a ceremony accomplished by the hermit-priest Wiswamitra with the help of Rama and Lakshmana. In accordance with the Balinese philosophy of Tri Hita Karana (Three things: human-nature-divinity), we portrayed the harmony of human life constituted by correct relations between humans (pawongan, depicted by Rama and his supporters); the harmony of humans and the natural environment (palemahan, manifested by Rama’s respect for the forest locales, as well as our outdoor presentation site on the ocean shore); and the harmony of human with the divine (parahyangan, as we centered the show around a purification ceremony).

Wayang performances are entertainment in the form of spectacles that contain guidance for understanding life. The Surya Sewana performance philosophically celebrated Dewa Surya as the sun who warms and awakens humans, animals, and plant-life. We crafted the story with hopes of neutralizing disease and harmonizing the universe. Our aim was to purify and cure after pandemic lockdowns.

But our performance was pragmatic too; it was set on a beach which is the center of tourism, in a festival meant to impress national and international tourists with the best aspects of Balinese arts and culture. The wayang wong performance was an offering to revive the life of Bali’s tourism in a downturn due to COVID-19. We prayed that cultural arts presentations, folk crafts, and other creative endeavors, so dependent on support from Bali’s tourism, would revive and thrive. The show was our company’s effort to build collaboration of all parties—including tourism businesses, the government, and the community—in the needed economic revival via the return of tourists, post-pandemic.

The story of the sage-priest Wiswamitra, supported by Sri Rama and Lakshmana, carrying out the Surya Sewana ceremony to neutralize disaster used digital technology, story, setting, costume, dialogue, music, and choreography to promote an empirical outcome. Philosophically and religiously, we were using a Balinese mode of neutralizing disaster by inculcating group ceremonial behavior via the performing arts, honoring our religious heritage and our local wisdom. Practically, we were getting young viewers to understand the meaning of wayang wong practice while kick-starting our economy, getting tourism moving once more.

[1] For discussion of some of my earlier work and general ideas on the adaptation of traditional wayang in contemporary performance see Stepputat (2013) who found my work an “example for the way individual artists not only cope with but actively shape the globalized postmodern world of Balinese performing arts” and Sedana (2005) on what locals termed wayang skateboard, which had multiple puppeteers riding skateboards for smooth passes along an elongated screen, using digital projections and other innovations. Gold (2013) likewise has assessed my innovations.

[2] For additional reading on wayang wong in both Bali and Java, as well as some discussions about contemporary attempts to revive it, see Susilo (1984), Kam (1987), Soedarsono (1984, 1999, 2000), Paneli (2017), Widyastutieningrum (2018) and Ruastiti, Sudirga, and Yudarta (2021).

[3] For more on wayang wong and its place in Balinese dance see also Bandem 1983, 1993, 1996.

[4] For materials on tourism see Williams and Darma Putra (1997), Soedarsono (1999), Sadiartha (2016), Pitana (2011), and Ruastiti (2010), McKean (1973), Noronha (1979),Picard (1996), and Sanger (1988). For impacts of tourism and examples of how arts have been harnessed to remedy crises in tourism see Sedana (2005) and Kodi, Foley, and I Nyoman Sedana (2002).

[5] See Anggarini (2021).

[6] While the story was not directly about the Surya Sewana ritual of the Balinese priest for making holy water and, indeed, that ceremony is a ritual of Siwa [India’s Shiva], the title of the performance indirectly references this important practice. For discussion of this ritual and its importance in Balinese religious culture see Hooykaas (1966) and Stephen (2015).

[7] Each of these elements mentioned in the paragraph, in the teaching at ISI, is given a name in Sanskrit/Kawi (Old Javanese) derived terms: composing a story is sanggit lakon or tatwa carita, developing a plot is arsaning pangasr characterizations is jadma prawerti. Terms for scenic and staging technology and choices are dipa pradipta, maya prakerti and loka prabha rasmi; choreography is natya sancaya; dialogue is krida basita; and musical accompaniment is gurnita tama.

[8] A semarandhana orchestra is a hybrid gamelan set that I Wayan Beratha developed in the early 1980s by combining elements of the long popular gong kebyar gamelan and semar pegulingan, an older ensemble.

[9] For discussion of other such projects using media see Ruastiti, Sudirga, and Yudarta (2021); Sugita and Setini; and Anshori (2021) on drama gong, another Balinese genre.

References

Anggarini, Desy Tri. 2021. “Upaya Pemulihan Industri Pariwisata Dalam Situasi Pandemi Covid-19 (Efforts to Restore the Tourism Industry in the Covid-19 Pandemic Situation). Pariwisata (Tourism) 8, No. 1 (April). https://scholar.google.com/scholar?q=Upaya+Pemulihan+Industri+Pariwisata+Dalam+Situasi+Pandemi+Covid+-19&hl=en&as_sdt=0&as_vis=1&oi=scholart, accessed 20 May 2023.

Bourdieu, Pierre. 1990. “(Habitus X Modal) + Ranah = Praktik,” Pengantar Paling Komprehensif kepada Pemikiran Bourdieu (Comprehensive Introduction to the Thought of Pierre Bourdieu). Bandung: Jalasutra. [Trans. from Richard Harker, ed. 1990. An Introduction to the Work of Pierre Bourdieu: The Practice Theory. London: Macmillan Press Ltd.]

Bandem, I Made. 1983. Ensiklopedi Tari Bali (Encyclopedia of Balinese Dance). Denpasar: ASTI-Denpasar.

_____. 1996. Etnologi Tari Bali (Ethnology of Balinese Dance). Yogyakarta: Kanisius.

_____. 1993. Wayang Wong in Contemporary Bali. PhD, Wesleyan University.

_____ and Frederick Eugene deBoer. 1995. Balinese Dance in Transition: Kaja and Kelod. Kuala Lumpur: Oxford University Press.

Collier, Mary Jane. 1994. “Cultural Identity and Intercultural Communication.” In Intercultural Communication: A Reader, ed. by Larry Samovar et al., 53-61. Berlmont: Wadsworth.

Darmoatmojo, S. 1989. “Gunungan dan Studi Lingkungan Hidup” (The Tree of Life/Mountain and Environmental Studies.” Gatra, 22, IV.

Budiman, Arif. 2019. “Kolom Pakar: Industri 4.0 vs Society 5.0.” (Expert Column: Industry 4.0 vs. Society 5.0). https://ft.ugm.ac.id/kolom-pakar-industri-4-0-vs-society-5-0/, accessed 22 May 2023.

Foley, Kathy, and Karen Smith. 2015. “Kayon/Gunungan:Tree of Life/Cosmic Mountain.” Puppetry International 38: 4-7. https://static1.squarespace.com/static/55a7e9aee4b02395231deded/t/5e8b8778fa0b1d1af99e1df4/1586202510785/38-PI+FALL-WINTER+2015.pdf, accessed 22 May 2023.

Foley, Kathy, and I Nyoman Sumandhi. 1994. “The Bali Arts Festival: An Interview with I Nyoman Sumandhi.” Asian Theatre Journal 11, No. 2: 275-89. https://doi.org/10.2307/1124234, accessed 22 May 2023.

Hooykaas, Christiaan. 1966. Surya–Sevana. The Way to God of a Balinese Siva Priest. Verhandelingen der Koninklijke Nederlandse Akademie van Wetenschappen, Afd. Letterkunde, Nieuwe Eeeks, 72, No. 3. Amsterdam: Noord-Hollandsche.

Gold, Lisa. 2013. “Time and Place Conflated: Zaman Dulu (a Bygone Era) and an Ecological Approach to Change in Balinese Shadow Play Music.” In Performing Arts in Postmodern Bali. Changing Interpretations, Founding Traditions, ed. by Kendra Stepputat. [Grazer Studies of Ethnomusicology.] Aachen: Shaker.

Kam, Garrett. 1987. “Wayang Wong in the Court of Yogyakarta: The Enduring Significance of Javanese Dance Drama.” Asian Theatre Journal 4, No. 1: 29-51. https://doi.org/10.2307/1124435, accessed 14 July 2023.

Kodi, I Ketut, I Nyoman Sedana, and Kathy Foley. 2005. “Topeng Sidha Karya: A Balinese Mask Dance Performed by I Ketut Kodi with I Gusti Putu Sudarta, I Nyoman Sedana, and I Made Sidia in Sidha Karya, Badung, Bali, 16 October 2002.” Asian Theatre Journal 22, No. 2: 171-198. doi:10.1353/atj.2005.0030, accessed 14 July 2023.

Laurie, Robin. 2000. “Theft of Sita.” Inside Indonesia 64. Oct.-Dec. [published online 30 July, 2007]. https://www.insideindonesia.org/the-theft-of-sita, accessed 14 July 2023.

Mantra, Ida Bagus. 1996. Landasan Kebudayaan Bali (Foundations of Balinese Culture). Denpasar: Yayasan Dharma Sastra.

McKean, Philip F. 1973. “Cultural Involution: Tourists, Balinese, and the Process of Modernization in an Anthropological Perspective.” PhD, Brown University.

Noronha, Raymond, 1979. “Paradise Reviewed: Tourism in Bali.” In Tourism, Passport to Development? ed. by E. de Kadt, 177-204. New York: Oxford University Press.

Picard, Michel. 1996. Bali: Cultural Tourism and Touristic Culture. Singapore: Archipelago Press.

Paneli, Dwi Wahyu Wirawan. 2017. “Transformasi Pertunjukan Wayang Orang Komunitas Graha Seni Mustika Yuastina Surabaya.” (Transformation of the Wayang Orang Group Graha Seni Mustika Yuastina of Surabaya). Journal of Art, Design, Art Education And Culture Studies (JADECS) 2 No. 2: 74-97. http://journal2.um.ac.id/index.php/dart/article/view/2185, accessed 14 July 2023.

“Peraturan Daerah Provinsi Bali Nomor 5 Bali” (Provincial Regulation Number 5). 2020.

Tentang Standar Penyelenggaraan Kepariwisataan Budaya Bali (Regarding the Standard for Conducting Balinese Cultural Tourism). Denpasar: Province of Bali.

Picard, Michel. 1996. Bali Cultural Tourism and Touristic Culture. Singapore: Archipelago Press.

Pitana, I Gede. 2011. “Pemberdayaan dan Hiperdemokrasi dalam Pembangunan Pariwisata” (Empowerment and Hyperdemocracy in Tourism Development). In Pemberdayaan dan Hiperdemokrasi dalam Pembangunan Pariwisata (Empowerment and Hyperdemocracy in Tourism Development), ed. I Nyoman Darma Putra and I Gede Pitana, 1-17, Denpasar: Pustaka Larasan.

Ruastiti, Ni Made. 2010. Seni Pertunjukan Pariwisata Bali (Tourist Performance in Bali).Yogyakarta, Kanisius. http://repo.isi-dps.ac.id/3302/, accessed 22 May 2023.

_____, I Komang Sudirga, and I Gede Yudarta. 2019. “Perancangan Model Wayang Wong Inovatif Bagi Generasi Milenial Dalam Rangka Menyongsong Era Revolusi Industri 4.0 di Bali” (Designing an Innovative Wayang Wong Model for the Millennial Generation in the Context of Welcoming the Era of the Industrial Revolution 4.0 in Bali.” Seminar Nasional Fakultas Seni Pertunjukan, 59-66. https://eproceeding.isi-dps.ac.id/index.php/seminarFSP/article/view/17, Denpasar: Fakultas Seni Pertunjukan, Institut Seni Indonesia Denpasar [also http://repo.isi-dps.ac.id/3317/1/PROCEEDING%20SEMINAR%20INTERNATIONAL%20-Unhi-GAP-2019.pdf], accessed 14 July 2023.

_____. 2020. “Aesthetic Performance of Wayang Wong Millennial.” International Journal of Innovation, Creativity and Change 13, No. 7: 678-692. https://www.ijicc.net/images/vol_13/Iss_7/13793_Ruastiti_2020_E_R.pdf, accessed 14 July 2023.

_____. 2021. Wayang Wong Milenial (Inovasi Seni Pertunjukan pada Era Digital) (Millennial Wayang Wong [Innovative Performance for the Digital Era]). Jakarta: Jejak Pustaka.

Sadiartha, A. A. Ngurah Gede. 2016. Budaya Entrepreneurship Dalam Tradisi Masyarakat Hindu Bali (Culture of Entrepreneurship in the Tradition of the Hindu Balinese). Denpasar: Universitas Hindu Indonesia. https://docplayer.info/84994963-Oleh-a-a-ngurah-gede-sadiartha.html, accessed 22 May 2023.

Sanger, Annette. E. 1988. “Blessing or Blight? The Effects of Touristic Dance-Drama on Village Life in Singapadu, Bali.” In The Impact of Tourism on Traditional Music, 89-104. Kingston: Jamaica Memory Bank.

Sedana, I Nyoman. 2005. “Theatre in a Time of Terrorism: Renewing Natural Harmony after the Bali Bombing via Wayang Kontemporer.” Asian Theatre Journal 22, No. 1: 73-86. doi: 10.1353/atj.2005.0012 [https://muse.jhu.edu/issue/9579], accessed 29 July 2023].

Soedarsono, R.M. 1984. Wayang Wong: The State Ritual Dance Drama in the Court of Yogyakarta. Yogyakarta: Gadjah Mada University Press.

———. 1999. Seni Pertunjukan Indonesia dan Pariwisata (Indonesian Performing Arts and Tourism). Yogyakarta: Masyarakat Seni Pertunjukan Indonesia (MSPI) [with Art-line and Ford Foundation].

______. 2000. Masa Gemilang dan Memudar: Wayang Wong Gaya Yogyakarta (Rise and Decline: Wayang Wong of Yogyakarta). Yogyakarta: Tarawang.

Soeprapto, Sri, and Jirzanah. 2009. “Transformasi Nilai-Nilai dan Alam Pemikiran Wayang Bagi Masa Depan Jati Diri Bangsa Indonesia” (Transformation of Wayang Values and Thoughts for the Future of Indonesian National Identity). Jurnal Filsafat (Philosophy Journal) 19, No. 2: 147-164. https://doi.org/10.22146/jf.3444, accessed 14 July 2023.

Srdarov, Suzanne, and Lisa Widayati. 2022. “Sanur Village Festival 2022,” 13 Sept. 2022. https://mysanurmagazine.com/sanur-village-festival-2022/, accessed 20 May 2023.

Stephen, Michele. 2015. “Sūrya-Sevana: A Balinese Tantric Practice.” Archipel 89. doi.org/10.4000/archipel.492. http://journals.openedition.org/archipel/492, accessed 22 May 2023.

Stepputat, Kendra. 2013. “Using Different Keys: Dalang I Made Sidia’s Contemporary Approach to Traditional Performing Arts. In Performing Arts in Postmodern Bali. Changing Interpretations, Founding Traditions, ed. by Kendra Stepputat. [Grazer Studies of Ethnomusicology.] Aachen: Shaker.

Sugihamretha, I Dewa Gede. 2020. “Respon Kebijakan: Mitigasi Dampak Wabah Covid-19 Pada Sektor Pariwisata” (Response: Mitigating Covid-19’s Impact on Tourism). Jurnal Perencanaan Pembangunan: The Indonesian Journal of Development Planning 4 No. 2: 191-206. https://doi.org/10.36574/jpp.v4i2.113, accessed 29 July 2023.

Sugita, I Wayan, I Made Setini, and Yahya Anshori. 2021. “Counter Hegemony of Cultural Art Innovation against Art in Digital Media.” Journal of Open Innovation: Technology, Market, and Complexity 7, No. 2: 147-. https://www.mdpi.com/2199-8531/7/2/147, accessed 29 July 2023.

Susilo, Hardja. 1984. “Wayang Wong Panggung: Its Social Context, Technique, and Music.” In Aesthetic Tradition and Cultural Tradition in Java and Bali, ed. Stephanie Morgan and Laurie J. Sears, 117-161. Madison: University of Wisconsin, Center for Southeast Asian Studies. https://doi.org/10.3390/joitmc7020147, accessed 14 July 2023.

Sutawa, Gusti Kade. 2020. Pariwisata Bali dalam Ancaman Pandemi Covid-19 (Tourism in Bali during the Threat of the Covid-19 Pandemic). Denpasar: Aliansi Pariwisata Bali.

Williams, Lesley E., and I Nyoman Darma Putra. 1997. Cultural Tourism: The Balancing Act. Canterbury: Lincoln University. https://researcharchive.lincoln.ac.nz/handle/10182/875, accessed 14 May 2023.

Widyastutieningrum, Sri Rochana. 2018. “Reviving Wayang Orang Sriwedari in Surakarta: Tourism-Oriented Performance.” Asian Theatre Journal 35, No. 1: 99-111. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26533687, accessed 14 May 2023.