The sacred story of Bhatara Kala (God of Time) is presented for the sapuh leger (sweeping impurity) in Balinese shadow puppetry. The tale is derived from lontars (palm-leaf manuscripts) including Kala Tatwa (Reality of Kala), Kala Purana (Myth of Kala), and others. This symbolic story, related to magico-religious thought, provides guidelines for the community. This paper discusses five narratives in lontar versions of the tale, then notes the interpretation/analysis provided by Dalang I Made Sidja, a senior puppet master of the Balinese wayang tradition. Some of these ideas appeared in Indonesian in Wicaksana and Wicaksandita (2023).

I Dewa Ketut Wicaksana M.Hum is Rector of Institut Seni Budaya Indonesia (ISBI, Institute of Arts and Culture) in Papua.

Ni Diah Punamawati teaches in the puppetry program at Institut Seni Indonesia in Denpasar and writes on Balinese performance.

I Dewa Ketut Wicaksandita teaches in the puppetry program at Institut Seni Indonesia in Denpasar and has written on the work of Dalang Wija, Dalang Sidja, and other contemporary Balinese artists.

The Bhatara Kala play (lakon), performed in Balinese wayang parwa (shadow puppetry), distinguishes itself from other Balinese performances in that it enacts a play within a play. The frame narrative focuses on the eponymous Bhatara Kala (God of Time), demon son of the high god of the Hindu universe (Siwa, India’s Shiva, also known as Bhatara Guru [literally, God/Divine Teacher] and other names). Kala has a taste for human blood. Another major character is Dalang Samirana. This dalang (puppet master), who can go by other names, is usually an incarnation of a deity. In pakeliran (performance on the puppetscreen), Dalang Samirana presents a puppet show about how Bhatara Kala chases his prey.[1] Kala comes to a performance where the dalang is playing Kala’s own history and the show convinces him to mend his ways. Hence, those who have been in danger of being eaten by the demon are saved. This form of “puppet show within a puppet show” is rare in Balinese wayang and is related to a mythos and ritual purification that gives this performance sacred nuance. The story appears in a number of palm leaf manuscripts (lontars), some of which will be discussed below. But the tale is best known in its applied form—performance by a dalang in a ritual for individuals believed to be threatened by Kala/misfortune. Potential victims are purified, blessed with holy water, and so freed of Kala’s threat by watching the play.

This double vision—a work of art inset within a work of art—reminds one of the self-consciousness of modernist drama, but here it is an old trope. Such framing highlights the artifice of performance, commenting on the relationship of “art” and “reality.” Rather than imputing that the fictive is lightweight, the play gives art here great profundity. The show within the show becomes a starting point for self-knowledge on social and cultural realities within a framework of ethics and aesthetics: the fictive makes the god-demon (and by analogy those purified, and, potentially, all viewers) think humanely, understand morals, and refine their feelings (Ma’rifah 2020: 168). Demon Kala is re-formed by watching his fictive life; he grows up.[2]

This essay will primarily deal with the narrative and its psycho-religious exegesis using our ideas on myth and the guidance of Dalang I Made Sidja, a senior Balinese puppet master of Banjar Dana, Bona Village, Blahbatuh District, Gianyar Regency.[3] We will give an overview of the narrative, discuss the variations in the five Balinese lontar (palm leaf manuscript) versions of the story, and argue a psycho-social-religious intent for the narrative. While this paper will deal mostly with these written versions, these texts are studied by the Balinese dalangs who do the ritual performances, giving these sources importance. While we deal here with only Balinese versions, this tale as purification rite is performed in puppetry throughout the Indo-Malay world and may have links to other purification performance rites that involve puppets and mask performance, making it worthy of careful study.[4]

Background and Plot

In Hinduism a divine trinity forms the Tri Murti (Trinity—the creator [Brahma], the preserver [Wisnu], and the destroyer [Siwa]). Bhatara Kala (Fig. 1-2) is a demon son of Lord Siwa. Ideologically, there is a supportive philosophical relationship between Siwa as Pemerelina (Destroyer/Smelter) (Fig. 3) and Kala (Time) as a destructive force (Suweta 2019: 3). Change exists due to time (Kala) and this “demon” can be considered a materialization of the omnipotent power of the eternal divine, known as Sang Hyang Widhi Wasa (God) and is represented by Siwa/Bhatara Guru.

Though details of Kala’s story vary from version to version, the broad outline persists. Bhatara Brahma and Bhatara Wisnu have created too many human beings and their behavior gets out of control. Seeing this, Siwa becomes upset and decides to do yoga on Mount Sangka Dwipa, where he accidentally has a fiery ejaculation of sperm (kama) from which emerges a giant child, screaming for father and mother, and begging for food.

Bhatara Guru Aji Wisesa (Siwa) hears Kala’s plaints and grants Kala permission to eat humans under limited conditions. In one Balinese version of the story, his hunted victims become two children, named Rare Komara and Komari, who are born during sukra wage wuku wayang (a fraught time in the Balinese calendar); they are pursued by Kala.[5] They hide under a large log, but Kala sees them so they hide in the resonator of the gender (a musical instrument that accompanies wayang puppetry)while the puppeteer, in this version called, I Dibya (literally, “divine luster”) performs a sapuh leger otonan (birthday) ceremony with the story about Kala chasing prey. As the ceremony ends, Kala promises to stop eating children and says that this story/blessing is something to be played for those who are born in the period of wuku wayang.

Overview of Bhatara Kala

This research is largely descriptive of the wayang sapuh leger play, Bhatara Kala, using a socio-religious approach and analyzing five lontar texts as the primary data, discussing how this myth is sacred to Balinese Hindus. We also looked at wayang documentation, visualizations in fine arts, written scholarship, and interviewed Dalang I Made Sidja (b. 1933), maestro puppeteer who is accustomed to discussing the philosophy and performing ritual presentations of the Bhatara Kala story in Balinese wayang (see Darling 1984).

Lontar: Palm Leaf Manuscript Versions

Lontar versions of Bhatara Kala’s story are found in Bali. Some of these manuscripts, made of incised palm leaves darkened with lamp soot displaying the letters, have even been translated/published in Indonesian and English. We discuss five versions in this paper: [6]

1) Lontar Kala Tatwa (Reality of Kala) is found in Gedong Kirtya (K. 5104) in Singaraja in northern Bali, founded by the Dutch in 1928 as an archive of Balinese texts, as well as the Cultural Documentation Center (PUSDOK) in Bali (see also Nestrayana 2021 and https://sastrabali.com/lontar-kala-tatwa/).

2) Kidung Sapuh Leger from Gedong Kirtya (K. 645) is available in a translation by Hooykaas (1973, 220-43).

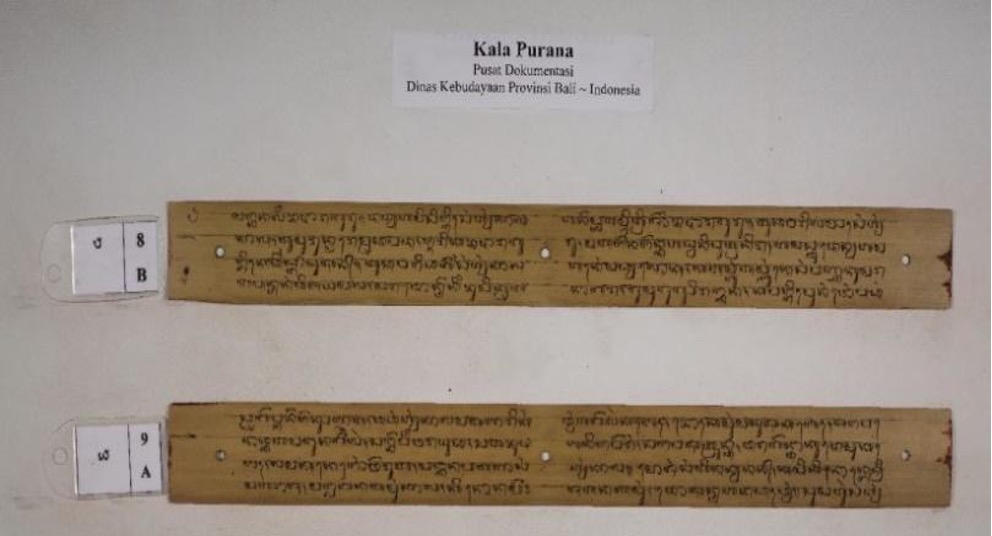

3) Lontar Kala Purana (Sacred Tale of Kala) is available in English (Hooykaas 1973, 170-187).

4) Lontar Kidung Sang Empu Leger (Poem of the Master of the Purification) is in the collection of the Literature Faculty of Udayana University, Denpasar, and translated into English by Hooykaas (1973, 244-268).

5) Lontar Cepa Kala (Riddles Put to Kala) from Gedong Kirtya (K. 504) is briefly discussed in Hooykaas (1973, 162-169).

These many existing texts on the Bhatara Kala themes show this myth was important to Balinese literati of the past. The tale with variations is or was performed in the puppetry of Java, Sunda, and Kelantan in Malaysia, showing significant spread. It is routinely connected with the puppeteer’s blessing of holy water to alleviate the potential for bad fortune.

Lontar Kala Tatwa (Kala’s Reality)

This lontar (Gedong Kirtya K. 5104) focuses on the story of Kala’s birth, whom he may “hunt” as his prey, and thereby clarifies the relationship between Kala and ritual purification in Bali.[7] Lord Siwa and his sakti/wife, Dewi Uma (also known as Bhatari Giri Putri and Durga), are flying above the sea when Siwa’s lust overcomes him. Uma rejects his sexual advances. As they struggle above the waves, he ejaculates. His kama (sperm) plummets into the ocean while Siwa and Uma return to heaven.

Soon Brahma and Wisnu cannot focus during meditation due to a massive churning in the waters. The chaos-causing sperm has coalesced becoming a hulking giant with a terrifying visage—Kala. The gods Brahma and Wisnu flee as Kala screams for his missing parents. All the gods, distraught, assemble with their magically empowered weapons to restore order. But the berserk Danuja Agung (Massive Ogre, that is Kala) defeats them all. Even Siwa cannot withstand Kala’s supernatural force.

Siwa asks why Kala is attacking heaven. The out-of-control son says he must find the identity of his parents. Siwa has Kala surrender his right fang, then acknowledges Kala as his own misbegotten son and Siwa then shares with this boy the god-like power to animate or destroy. Siwa names his son Sanghyang Kala (literally, God of Time). Kala is willing (ri kalania) to surrender his tusk—tooth filing in Bali is the ritual coming of age ceremony—defanging matters. Siwa then gives permission to Kala to eat those who sleep in the late afternoon, children who cry at night, people who thoughtlessly meander mid-road at noon, and others who fall under certain conditions. Kala is not allowed to eat those who progress with deliberation on their journey, and he must deliver good fortune to those who understand their origin and task in life.

Kala then descends to earth to live in the graveyard where his mother, Durga (a terrifying manifestation of Uma), lurks.[8] In the bale agung (main pavilion) of the temple by the cremation ground the demonic female is called Juti-Srana (a manifestation of Uma/Durga) and so she is the appropriate caretaker for this demon son. At the graveyard, Kala becomes the leader of the lower demons [9] and all diseases (gering sasab merana). He roams the Pura Dalem (temple of death/cremation temple, one of the three temples in each Balinese village and the one dedicated to Siwa).

Kidung Sapuh Leger (Kidung of Sweeping Impurity)

This lontar (Gedong Kirtya K. 645) consists of 123 bait (stanzas), divided into tembang macapat (Middle Javanese chanted verse/songs) written in the metrical forms known as sinom, pangkur,and durma.[10] Instead of the bare-bones parent-child plot of the previous telling, this version focuses on sibling rivalry and the hunt for prey.

Siwa has two children, both born in wuku wayang. The eldest is the ogre Bhatara Kala and the youngest is the handsome and petit Rare Kumara. Kala claims he should be able to eat his brother, since Kumara’s wuku wayang birth makes him legitimate prey (Fig. 4). But Siwa asks for a seven-year wait until Kumara “grows up.” Siwa then trickily ensures Kumara will remain forever small. After waiting three years during which Kumara fails to grow, Kala becomes impatient. Siwa helps Kumara escape to the kingdom of Kertanegara led by King Mayasura. Kala follows, attacking midday loiterers (sande-kala) on the road.

(Source: https://pandejuliana.wordpress.com/)

Kumara hides in a bundle of bamboo stalks, a pile of wood, and the chimney area of a kitchen. Kala curses those who have gathered such materials or whose actions may have helped Kumara escape. King Mayasura tries to protect Kumara, but all the king’s horses and men are of no use. Kumara is in Kala’s jaws when Siwa and Uma, riding on their white bull, Nandi, appear. Since it is noon (Kala’s hour to wreak havoc), Siwa, to buy time, poses a riddle, asking: What has asta pada, sad lungayan, catur puto, dwi purusa, eka bagha, eka egul, trinabi, sad karna, dwi srenggi gopa-gopa, sapta locanam (Eight feet, six arms, four testicles, two penises, one vagina, one tail, three navels, six ears, two horns, and seven eyes)? The answer, though Kala cannot perceive it, is right in front of him—the divine parental couple riding bull Nandi.[11] The quiz takes enough time for the sun to move, so Kala loses his high noon right to eat his parents. Kala kicks the coconut tree which will forevermore bend because it failed to block the sun’s rays.

Brother Kumara, still running, arrives at a wayang performance and begs for protection. The dalang hides him in the bamboo resonator tube of one of the gender (metallophone instruments that accompany the show). The famished Kala devours the elaborate food offerings (called banten, caru, bali) prepared for the puppet show. When the dalang demands recompense for the food consumed, Kala pays with a mantra the puppeteer will use to purify living things, saying:

May Grandfather Dalan[g] receive the power to free all living things from every kind of evil, and have the power to exorcize the dead, so that they, with their children and their [children’s] children, may have deliverance (Hooykaas 1973, 241).

The offerings—food, puppetry, music—have, since that time, been paid to Kala for the welfare of the children of tumpek/wuku wayang.

This is a more dramatically complex version of the story than the Kala Tatwa discussed earlier. The fraught family dynamics of the two siblings and perplexed parents tend to be portrayed in most wayang sapuh leger performances by contemporary puppet masters. This is a tale of a divine family feud that makes for rich storytelling.

Kala Purana (Sacred Tale of Kala)

This lontar version (Fig. 5-6) consists of around ninety couplets in the form of palawakya (prose).[12] The plot again is similar to Kidung Sapuh Leger. By the end, Kala feels indebted to the dalang for the offerings that satisfy his hunger and end his thirst for blood. Kala gives the dalang authority to purify (nglukat) all human beings from impurities (sudhamala, literally “end to evils”); these two terms, therefore, can be used to describe the purification ceremony. As Kumara returns to heaven, Kala announces:

I … confirm that though art, the aman[g]ku [enlightened dalang] of the Dharma Pavayanan [Book of the Wayang] . . . [will henceforth be] entitled to provide all people with the [toya] panglukatan [water of purification] . . . so that to the end of time they shall be exorcized by the pan[g]lukatan of Mpu Leger [Master/Poet of Purification] (Hooykaas 1973, 185).

A list of the required offerings is given[13] and it is agreed that Kala can only attack those who are abroad at noon, dusk or midnight.[14]

Kidung Sang Empu Leger (Kidung of the Master of Purification)

This poem consists of ninety-three stanzas in macapat Javanese poetic verse forms (see Hooykaas 1973, 245-266). This iteration involves, once more, a complex family drama, but marital problems between the divine couple are more foregrounded.[15]

Siwa is ill and Uma seeks cow’s milk as medicine. An old cow herder (in reality, Siwa in disguise) claims to have never had sexual relations and demands intercourse as payment for milk. Uma refuses but, needing the antidote to save Siwa, relents, conveniently moving her vagina to her thigh to lessen the contact. When Uma brings the precious milk, Siwa questions how she obtained it, having taken nothing for payment. The divine couple’s son, the elephant-headed Sanghyang Gana (God Ganesha), consults the lontar manuscript Aji Tenung (Book of Divination) that tells all that has transpired. Uma, in anger, assumes her terrifying manifestation as Durga, burning part of the manuscript, and her younger son Kumara tears up the rest. Henceforth knowledge of past-present-future will always be imperfect. Gana, in anger, wants to kill Kumara, but Siwa persuades him to wait until the boy is grown, and, as in Kidung Sapuh Leger, makes sure Kumara will stay forever tiny and sends him to earth.

Dewi Uma, pregnant by the cow herder/Siwa, gives birth to an egg that looks like an iron rice cooking pot. Hermit-god Bhatara Wrhaspati suggests throwing the egg in the sea, but it resurfaces. Siwa’s right-hand man, Bhatara Narada, suggests burying it in the earth, but it pops out again. Siwa tries burning it, but it remains indestructible. Soon a giant, bald, and bawling being emerges. Already impervious to water, earth, and fire, the child now wants to eat flesh of gods or humans. Heaven empties as all the gods flee, so ravenous Kala tries to find prey on earth. Siwa limits the son’s hunting to certain times and set people.

Surya (God of the Sun, this time not Siwa) and Uma come riding at noon on Bull Nandi. Kala fails to solve the customary riddle and releases them. A priest, Bhagawan Trnawindu, has two children born during wuku wayang, a male Rare Brata and a daughter Rare Brati. As Kala comes, Rare Brata hides by a coconut tree; Kala curses the coconut to bend for shielding him. Brata escapes through the smoke vent of a fireplace; Kala curses anyone who cooks carelessly. Sang Hyang Paramesti/Siwa descends to earth as an amangku dalang (puppeteer who can do purifications/bless holy water, an “enlightened” dalang). Using aji astagina (eightfold mantra), Siwa creates a puppet stage, and devises the offerings (banten) for Sapuh Leger’s sweeping away of impurities.

The wuku wayang-born Rare Brata hides behind the dalang on stage amidst the gender musicians. Kala, distracted by the music and the show, gobbles up the offerings. The dalang gets Kala’s promise that he will henceforth eat offerings and not people. Brata is safeguarded via the dalang’s holy water (tirta sudhamala), so Siwa’s work as puppet master is done, and he returns to heaven.

This version has complex family dynamics, with female adultery (Uma), male jealousy/trickery (Siwa), and sibling rivalry (Gana and Kumara). The elephant-headed Gana threatens Kumara early on, but then disappears as Kala manifests, and attacks, first the heavens, but then the world. The boy, Brata, who throws himself on the dalang’s mercy, is here a wuku wayang-bornhuman, much like the children for whom the sapuh leger ceremony is performed every six months.

Cepa/Japa Kala (Riddles Put to Kala)

This lontar, Japa Kala (Gedung Kirtya K. 504), is in the form of palawakya (prose) and quite streamlined. It focuses on parent-child relations rather than the wider divine family dynamic (for translation see Christiaan Hooykaas 1973, 162-169). It tells the story of the birth of Kala from kama salah (spilt seed/sperm), beginning with the question: where did Kala come from? Answering, he came from diamond sperm (manik sphatika) attended by the heavenly dewata nawa sanga (nine gods-guardians of the eight directions and the center, who are the basis of the Balinese pantheon) (p. 163). Because Kala is born in a crystal-mass form, the nine gods smash the rock-sperm that is Kala with their respective weapons. Kala emerges, with his sharp teeth, thick hair, looming body, and thunderous voice that splits the sky.

The gods flee, helter-skelter. Guru/Siwa sends Kala to lurk at the crossroads (catur patha agung) of north, south, east, and west, where he may seize those walking at noonday and those sleeping late (sande–kala). Kala devours 5,500 people from the east; 9,900 people from the south; 4,400 from the north; 7,700 people from the west; and 8,800 from the center (p. 165). Humans flee, hiding in ravines, incessantly begging Siwa for relief. Siwa and Uma (here called Sri) ride out on Nandi. Dismounting, they transform into cowherders (gopa-gopi) to meet Kala. Siwa poses the riddle and Kala, as always, is flummoxed. Siwa gives permission to attack victims of earthquakes, floods, fallen trees, etc. The manuscript continues with a description of offerings and mantras. The foci in this version are the genesis of Kala from divine sperm, the magnitude of victims he slays, and the delivery of offerings.

Myth in Performance

The Kala play is the special repertoire of the wayang sapuh leger performance and highlights the role of the artist and artistic practice in society. We see the story of Kala as magico-religious myth, providing direction to a group of people (see Peusen 1994, 37). The structural approach to narratives proposed by Claude Lévi-Strauss has stimulated research on mythology from an anthropological perspective. Lévi-Strauss felt that the elements of myth must be studied not in isolation from each other, but rather, as with language—sounds and phonemes—as things that only make sense if we examine all the parts as they combine and relate to other elements (Rahmanto 1993: 322).

The importance of artistic beauty/enchantment (here, wayang performance) is an important cultural myth-message of this play. To understand the story textually and contextually one must understand the religious way of thinking of the Hindu community in Bali. In Hindu aesthetics, a work of art must fulfill six conditions (sad-angga): 1) rupa-bheda (secrets of form), the images must be suited to ideas they are meant to convey; 2) sadrsya, clarity in the vision in relation to reality; 3) pramana (proportion), rightness in size; 4) warnika-bhangga (coloring), good composition/coloring; 5) bhawa (bhava, feelings), creating the right atmosphere and radiance; and 6) lawanya (grace), having beauty and charm (see Agastia 1996). The aesthetics of wayang are embodied in kawi dalang (creativity of the performer) and suggest how Balinese puppeteers develop a performance so that it has aesthetic power based on its initial source/plot (Sedana 2002). Sedana theorizes creativity in plot, which he divides into four parts—a) transforming the narrative into dialogue form; b) choosing the story for the occasion; c) composing the play; and d) creating a new story (Sedana 2002, 68-123). Through this kawi dalang method, in presenting the play about Bhatara Kala, a puppeteer who has studied such lontar versions as those discussed above is able to infuse values into the audience’s imagination, such that the beauty (sad angga) communicates the sacred meaning. The story can lead them towards intellectual and spiritual intelligence. Thus, wayang performance in Bali, especially this particular tale, is cosmically based (Sedana 2016: 35): a beautiful atmosphere (lango) is formed and can convey the theological-aesthetic dimension to society.

The conflict in the tale of Bhatara Kala, as with most traditional wayang stories, is rooted in spiritual thought. A spiritual struggle—inner conflict in the deep recesses of the human heart between good and evil (the microcosm)—is envisioned as a contest between white (mystical) power and black (magical) power, which in wayang must end with a victory of white power (Mangkunagoro 1957, 3). This play can be seen as beginning with the growth of a fetus in the mother’s womb. The diamantine mass (manik sphatika) is kama jaya (sperm), falling into the “ocean,” which represents the womb of a mother (compared here to ibu pertiwi, mother earth). The kama jaya (sperm of the father) meets with kama ratih (egg from the mother): these are the forerunners of life. When they unite, they develop into a more perfect form, a baby. During this period, the baby’s body is perfect, but still small.

Dalang I Made Sidja when we interviewed him said he sees the story of the dewata nawa sanga (gods of the nine cardinal directions) whose weapons stab Kala in lontar Japa Kala as a representation of the process of forming all parts of a human body in the mother’s womb, giving life to the baby. As Sidja sees it, Lord Wisnu’s weapon (Chakra, Discus, North) forms the bile (empedu); Sambhu’s weapon (Tisula/Trident, Northeast) forms the throat (tenggorokan); Lord Iswara’s weapon (Wajra/Vajra, East) forms the heart (jantung); Dewa Maheswara’s thurible (Dupa/Incense Burner, Southeast) forms the lungs (paru-paru); Lord Brahma’s weapon (Ghada/Club, South) forms the liver (hati); Lord Rudra’s prod (Moksala, Southwest) forms the intestines (usus); Dewa Mahadewa’s weapon (Nagapasa/Snake Arrows, West) forms the kidneys (ginjal); Dewa Sangkara’s weapon (Angkus/Fire Arrows, Northwest) forms the spleen (limpu); while Lord Shiva’s weapon (Padma/Lotus, Center) forms the core/center of being (pusat hati).[16]

Bhatara Kala is the personification of a baby arriving from his mother’s womb; he will cry, a sign that a baby is born healthy. Siwa (the father), acknowledges the child as his son and gives him the name Sanghyang Adi Kala. The thirst for blood means that a baby needs food in the form of mother’s milk and soft food such as porridge or young coconut flesh. Until a newborn reaches his first oton (six months of the Balinese calendar and considered one year/one cycle), he is treated like a god—thought to be sacred. Bhatara Kala [here the child] begins with acts of preying, greed, and announcing curses, even attacking his own parents. But soon Bhatara Kala is defeated by the puppeteer both ritually and mystically. The dispute between Bhatara Kala and the puppeteer ends with Kala’s submission, a sign that the hard effort of personal moral maturation is accomplished. The child is socialized/humanized.

Conclusion

This story of Bhatara Kala concerns ethical values related to human life, making a bridge between the bhuana agung (macrocosm/world of the gods/natural world) and bhuana alit (microcosm/development of the individual/human society). The message is that it is imperative for humans to find harmony in existence. This is in accord with the Balinese analogy of kadi manik ring cacupu (like a fetus in the mother’s womb): humans are the manik (diamond/fetus) and the universe/nature is the cecupu (container/womb). Philosophically, human life must be limited in its freedom. Kala has freedom in devouring certain victims as permitted by Siwa but must learn the nature of the bhuana agung (macrocosm), which has three levels, namely, swah loka (upper/divine realm), bhuah loka (middle/human realm of earthly life), and bhur loka (underworld/demonic realm). The three constitute a unity and must be harmonized. The puppeteer who performs wayang uses creativity of kawi dalang and explores and unites, fragment by fragment, this tale bearing aesthetic-religious conceptions including the characteristics of divinity, the demonic, and the human. The puppeteer assembles cultural values to present on the puppet screen, using dimensions of belief and beauty via music-movement-dialogue, so that the show triggers religious reflection. In so doing, the viewers will understand what the Kala Tatwa (Pusdok 1987, 3) teaches:

Sira maka aran kamanusa jati, ki manusa jati juga wenang arok lawan Bhuta Kala Durga, Bhuta Kala Durga wenang arok lawan Dewa Bhatara Hyang, karaning tunggal ika kabeh, sira manusa, sira Dewa, sira Bhuta. Bhuta ya Dewa ya Manusa ya.[17]

What is called the true human, the true human unites with Bhuta Kala Durga [Uma], Bhuta Kala Durga also unites with Dewa Bhatara Hyang/Siwa, because all of them are one, Human-God-Demon. Demon-God-Human.

[1] Whatever the puppeteer’s name in various versions, the term usually implies an enlightened being, usually identified with a manifestation of Siwa.

[2] This essay will primarily deal with Indonesian sources and be confined to the Balinese versions of the tale. For discussions of this or related ritual stories often dealing with different areas of Indonesia: for Java see Beatty (2021), Headley (2000), Mariani (2022, 2016), and Santiko (1980); for Bali see Christiaan Hooykaas (1972, 1973), Jacoba Hooykaas (1961), Hobart (1987, 2003), and Stephen (2002); and Keeler (1992) who compares Bali with Java. For translations of ritual plays with related narratives and discussion of ideas for Cirebon area of Java see Cohen (1999) and for East Java see Clara van Groenendael (1999). For Sunda/West Java see Foley (2001).

[3] For more on Sidja see Darling (1984).

[4] For insight into the tale in Malaysia see Cuisinier (1957) and for related purifications dealing with related Balinese Siwa-Durga/Uma stories, especially regarding the female principle, see Ariati (2009), Cerita and Foley (2022), Foley (2022), Christiaan Hooykaas (1974), Lovric (1987), and Hobart (2003). Headley (2004) discusses the female divine principle in Java.

[5] Sukra wage wuku wayang is the most crucial day and falls on a Saturday (seventh day of the twenty-seventh wuku out of the thirty wuku that make up the Balinese year of 210 days). However, the performance is recommended for anyone born during that twenty-seventh week. Tumpek wayang is when sapuh leger is required. Like Friday the thirteenth in Western thinking, it is a day fraught with meaning. Offerings for puppets, masks, and other art objects are normal.

[6] “K.” will indicate that the location of the lontar manuscript is at Gedong Kirtya, Singaraja, the largest repository on the island. See the lontar section in references for names of lontar which we accessed, but do not always discuss in detail. To see images of a sample lontar visit https://archive.org/details/kala-tatwa/mode/1up, accessed 19 May 2021. Other versions, not discussed, are Kakawin Sang Hyang Kala (Old Javanese Poem of God Kala, K. 2102, collected from Banjarangkan, Klungkung) and Tutur Wiswa-Karma (Teaching of Wiswakarma K. 1611, collected from Peguyangan, Singaraja); both are discussed in Hooykaas (1973: 210-219). Lelampahan Wayang Sapuh Leger (K. 2244, see Hooykaas 1973, 188-209), again not discussed here, is close in content to Kidung Sang Empu Leger (4 above), though there is the deviation from normal versions in that Bhatara Kala is defeated by Prabu Arjuna Sasrabahu (Arjuna of 1000 Arms), who is an incarnation of Wisnu [Vishnu], not Siwa, as is more routine. Another related lontar Siwagama, published by Pusdok (1986) references a somewhat related tale of Siwa and Durga becoming demons.

[7] Stephen 2002: 67-69 discusses this work in relation to ritual offerings as a method of returning gods from their terrifying to their peaceful forms. See also Acri and Stephen (2018).

[8] Bhatari Durga in the graveyard is also associated with Kalika who is sometimes seen as a demonic daughter of Uma and Siwa and originator of witchcraft; these characters play significant roles in the Calonarang story (see Stephen 2002: 84).

[9] Names for some of these groups are bhuta-kala, durga, pisaca, wil, danuja, kingkara, denawa, among others.

[10] This Javanese verse style of macapat dictates the number of lines in a stanza, the number of syllables in a verse, and the letter at the end of each line; for the English version see Christiaan Hooykaas (1973: 220-243).

[11] The riddle solution is eight legs=bull [4], Uma [2], and Siwa [2]; six arms=Shiva [4] and Uma [2]; four testicles=Shiva [2] and Nandi [2]; two penises=Shiva [1] and Nandi [1]; one vagina (Uma); one tail (Nandi); two horns=Nandi [2]; seven eyes=Uma [2], Nandi [2], and Siwa [3, including Siwa’s cudamani/third eye].

[12] Christiaan Hooykaas (1970, 170-187), who compared four versions of this lontar, lists eighty-nine recurring verses (see p. 187 for manuscript sources)¥.

[13] See Christiaan Hooykaas (1970, 185). For further discussion of offerings in demon purification rites see Stephen (2002: 71-72) and Acri and Stephen (2018).

[14] Christiaan Hooykaas (1973, 187), see also an original lontar image https://palmleaf.org/wiki/kala-purana, accessed 19 May 2023. In this version we get more specifics of when each child is born. Kala was born later in the afternoon (sandhya-wela) on the Thursday of the wayang week while his younger brother Sang Hyang Panca-Kumara was born on the more fraught Saturday kliwon of puppet week (wuku wayang) (Hooykaas 1973, 170). Kala tries to claim Kumara as victim when Kumara is five. The riddle scene is developed as “Kala became angry. He wanted to devour his parents. He opened his mouth wide like a ravenous lion” (Hooykaas 1973, 179). See also Stephen (2002).

[15] See Jacoba Hooykaas (1961) for more on this version.

[16] Sidja, personal interview, 13 November 1996.

[17] http://radheyasuta.blogspot.com/2013/01/lontar-kala-tatwa.html see paragraph 16. Lontar Kala Tatwa 2013. 31 Jan., accessed 30 July 2023.

References

Acri, Andrea, and Michele Stephen. 2018. “Mantras to Make Demons into Gods: Old Javanese Texts and the Balinese Bhūtayajñas.” Bulletin de l’École Française d’Extrême-Orient 104: 141–204. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26753404, accessed 7 July 2023.

Agastia, Ida Bagus Gede. 1996. Nilai Moral dan Spiritual dalam Seni Pertunjukan (Moral and Spiritual Level in Performance). Denpasar: Warta Hindu Dharma, Parisada Hindu Dharma Indonesia Pusat.

Ariati, Ni Wayan Pasek. 2009. The Journey of a Goddess: Durga in India, Java and Bali. PhD diss., Charles Darwin University. https://researchers.cdu.edu.au/en/studentTheses/the-journey-of-a-goddess, accessed 15 April 2023.

Beatty, Andrew. 2012. “Kala Defanged Managing Power in Java Away from the Centre.” Bijdragen Tot de Taal-, Land- En Volkenkunde 168, No. 2/3: 173–194. http://www.jstor.org/stable/41581000, accessed 15 April 2023.

Cerita, I Nyoman, and Kathy Foley. 2022. “Balinese Calonarang in Performance.” Ecumenica 15, No. 1: 42-65. doi: https://doi.org/10.5325/ecumenica.15.1.0042, accessed 15 April 2023.

Clara van Groenendael, Victoria. 1999. Released from Kala’s Grip: A Wayang Exorcism from East Java. Performed by Ki Sarib Purwacarita, ed. by Joan Suyenaga. Jakarta: Lontar.

Cohen, Matthew. 1999. Demon Abduction: A Wayang Ritual Drama from West Java. Performed by Basari, ed. by Joan Suyenaga. Jakarta: Lontar.

Cuisinier, Jeanne. 1957. Le Theatre D’Ombres A Kelantan. Paris: Gallimard.

Darling, John. 1984. Master of the Shadows: A Balinese Puppeteer (Film). Human Face of Indonesia 5, Canberra, Australian Capital Territory: Australia. National Film and Sound Archive.

Foley, Kathy. 2001. “Introduction: The Origin of Kala: A Sundanese Wayang Golek Purwa Play by Abah Sunarya and Gamelan Giri Harja I.” Asian Theatre Journal 18, No. 1: 1-58. doi:10.1353/atj.2001.0002,accessed 14 April 2023.

_____. 2022 “Bali’s Rangda and Barong in Cosmic Balancing.” In Monsters in Performance: Essays on the Aesthetics of Disqualification, ed. by Michael Chemers and Analola Santana, 1-21. New York: Routledge https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003137337, accessed 14 April 2023.

Headley, Stephen C. 2000. From Cosmogony to Exorcism in a Javanese Genesis: The Spilt Seed. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

_____. 2004. Durga’s Mosque: Cosmology, Conversion and Community in Central Javanese Islam. Singapore: Institute of South East Asian Studies.

Hobart, Angela. 1987. Dancing Shadows. London: KPI.

_____. 2003. Healing Performances of Bali. New York: Berghahn Books.

Hooykaas, Christiaan. 1972. “Kala di Java dan Bali” (Kala in Java and Bali). In India Mayor, Volume Peringatan yang Disajikan kepada J. Gonda, (Greater India, Volume Offered in Memory of J. Gonda), ed. by J. Ensink and P. Gaeffke. Leiden: Brill.

_____. 1973. Kama and Kala: Materials for the Study of Shadow Theatre in Bali. Amsterdam, London: North Holland Publishing Company.

____. 1974. Cosmogony and Creation in Balinese Tradition. [KITLV: Bibliotheca Indonesica. No. 9] The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff.

Hooykaas, Jacoba. 1961. “The Myth of the Young Cowherd and the Little Girl.” Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land-, en Volkenkunde 117: 267-278.

Keeler, Ward. 1992. “Release from Kala’s Grip: Ritual Uses of Shadow Plays in Java and Bali.” Indonesia No. 54: 1-25. https://www.jstor.org/stable/3351163, accessed 14 April 2023.

Lovric, Barbara. 1987. Rhetoric and Reality: The Hidden Nightmare: Myth and Magic as Representations and Reverberations of Morbid Realities. Ph.D., University of Sydney. https://ses.library.usyd.edu.au/handle/2123/1599, accessed 13 Nov. 2020.

Mangkunagoro VII, K. 1957. On The Wayang Kulit (Purwa) and its Symbolic and Mystical Elements, trans.by Claire Holt. Ithaca: Cornell Univ. Southeast Asian Studies.

Mariani, Lies. 2012. “Ruwatan di Taman Mini Indonesia Indah: Kajian Dinamika Ruwatan” (Healing Performance at Taman Mini Indonesia: Dynamic Effort), Fourth International Conference on Indonesian Studies: “Unity, Diversity, and Future.” [Bandung: Universitas Padjadjaran] [also https://icssis.files.wordpress.com/2012/07/09102012-791.pdf, accessed 7 July 2023].

_____. 2016. “Ritus Ruwatan Murwakala di Surakarta” (The Rite of Ruwatan Murwakala in Surakarta). Umbara 1, No. 1. <http://jurnal.unpad.ac.id/umbara/article/view/9603>, accessed 7 July 2023.

Ma’rifah, Indriyani. 2020. “Peran Sastra Dalam Membangun Karakter Bangsa (Perspektif Pendidikan Islam)” (Role of Literature in Developing National Character [Perspective in Islamic Education]). Titian: Jurnal Ilmu Humaniora (Titian: Journal of Humanities). 4, No. 2. https://mail.online-journal.unja.ac.id/titian/article/view/11343, accessed 7 July 2020.

Peursen, C[ornelius] A. van. 1994. Strategi Kebudayaan (Strategy of Culture). Yogyakarta: Kanisius.

Rahmanto, Bernardus. 1993. “Ke Arah Pemahaman Lebih Baik Tentang Mitos” (Toward a Better Understanding of Myths). Majalah Basis (Basis Magazine). 43, No. 9: 322ff.

Santiko, Hariani. 1980. Ruwat: Tinjauan dari Sumber-Sumber Kitab Jawa Kuna dan Jawa Tengahan (Ruwat: Overview of Old Javanese and Javanese Religious Sources). Series to Publish Research No 3. Jakarta: Literature Faculty University of Indonesia.

Sedana, I Nyoman. 2002. Kawi Dalang: Creativty in Wayang Theatre. Ph.D., University of Georgia.

_____. 2016. “Teori Seni Cipta Konseptual” (Conceptual Theory of Creating Art). Prosiding Seminar Nasional Seni Pertunjukan Berbasis Kearifan Lokal (National Proseminar of Performance on the Basis of Local Creativity) 35. Denpasar: Institut Seni Indonesia.

Stephen, Michele. 2002. “Returning to Original Form: A Central Dynamic in Balinese Ritual.” Bijdragen Tot de Taal-, Land- En Volkenkunde 158, No. 1: 61-94. <http://www.jstor.org/stable/27865814>, accessed 7 July 2023.

Suweta, I Made. 2019. “Teks Lontar Kala Purana (Kajian Filosofis, Simbolis, dan Nilai)” (The Text of the Palm Leaf Manuscript Kala Purana [Studies of Philosophy, Symbolism, and Values]). Genta Hredaya 3, No. 1. <https://stahnmpukuturan.ac.id/jurnal/index.php/genta/article/view/444>, accessed 7 July 2020.

Wicaksana, I Dewa Ketut, and I Dewa Ketut Wicaksandita. 2023. “Wayang Sapuh Leger: Sarana Upacara Ruwatan di Bali” (Wayang Sapuh Leger: Method of the Purification Ceremony in Bali). Jurnal Penelitian Agama Hindu (Journal of Research on Hindu Religion) 7, No. 1. <https://www.researchgate.net/publication/367206409_Wayang_Sapuh_Leger_Sarana_Upacara_Ruwatan_di_Bali>, accessed 30 July 2023.

Lontar Consulted

Cepa Kala (K. 504). Singaraja: Gedong Kirtya.[See also Christiaan Hooykaas 1973, 162-169 and Lontar Tatwa Japakala (ms. 19397). Romanised transcription by I Dewa Gede Catra of a manuscript owned by I Made Sutha (Tampwagan, Amlapura)].

Kakawin Sang Hyang Kala (K. 2102) [collected from Banjarangkan, Klungkung]. Gedong Kirtya, Singaraja.[See Christiaan Hooykaas 1973, 210-219.]

Kala Purana. Girya Kadampal, Krambitan, Tabanan. [See also Christiaan Hooykaas 1973, 170-187.]

Kala Tatwa (also Kala Tattwa,K. 5104) Singaraja: Gedong Kirtya. [See also Tattwa Kala 2005.In Alih Aksara dan Alih Bahasa Lontar Tutur Adna Bhuana, Tattwa Kala, Ajiswamandala (Romanization and translation of the palm leaf manuscripts Adna Bhuana, Tattwa Kala, Ajiswamandala.) Office to Document Balinese Culture. Denpasar: PUSDOK].

Kala Tatwa. 1962, transcribed by I Gusti Ngurah Alit. Denpasar: Fakultas Sastra, Universitas Udayana.

Kala Tatwa. 2015. https://sastrabali.com/lontar-kala-tatwa/, accessed 7 July 2023.]

Kala Tatwa. 2021. In Buku Salinan Dan Terjemahan Lontar Kala Tatwa (Book of Publishing and Translating the Palm Leaf Manuscript Lontar Kala Tatwa), trans. by I Nyoman Nestrayana. Denpasar: Whidi Sastra.

Kidung Sang Empu Leger.Faculty of Literature. Denpasar: Universitas Udayana.

[See also Christiaan Hooykaas 1973, 244-268).]

Kidung Sapu Leger (K. 645). Singaraja: Gedong Kirtya. [See also Lontar Kidung Sapuh Leger. 1974. by Listibya.Denpasar: Bali, Majelis Pertimbangan dan Pembinaan Kebudayaan (Listibya) Daerah Bali, and Christiaan Hooykaas 1973, 220-43].

Lelampahan Wayang Sapuh Leger (K. 2244). Singaraja: Gedong Kirtya. [See also Listibiya Bali 1974, along with Lontar Kala Tatwa (Nestrayana, trans. 2021), and Christiaan Hooykaas 1973, 188-209.]

Siwagama. 2002. [Manuscript of Ida Pedanda Made Sidemen of Geria Sanur]. Denpasar: Dinas Kebudayaan Propensi Bali [Pusdok].

Tutur Wiswa-Karma (K. 1611) [collected from Peguyangan, Singaraja]. Singaraja: Gedong Kirtya. [See also Christiaan Hooykaas 1973, 210-219.]