Puppets: Expressions of Cultures. Exhibition curated by Chen Wan-Ping, Lee Tai-Ling, Kuo Chao-Ling, and Fang Jiann-Neng. National Taiwan Museum, Taipei, Taiwan, December 31, 2024–August 31, 2025.

On view at the National Taiwan Museum until August 31, 2025, the exhibition Puppets: Expressions of Cultures offers a glimpse into one of the world’s most comprehensive archives of puppetry arts and provides a rich, multifaceted journey through diverse performance traditions. Initially housed in the Taiyuan Asian Puppet Theatre Museum, founded by Dr. Paul Lin, the collection was transferred to the National Taiwan Museum in 2020 after more than two decades of private stewardship. From a donation of over 11,000 artifacts, including different types of puppets, puppet stages, masks, costumes, props, statues, scripts, and more, one hundred twenty-five pieces were selected for display, each inviting reflection on puppetry not only as a performative craft, but as a living vessel of memory, tradition, and imagination across Asia and beyond.

Organized into three thematic chapters, “Open the Puppet Treasure Box,” “The Multiple Faces of Puppet Play,” and “The Kaleidoscope of Puppetry,” the exhibition reveals the diverse nature of puppetry and an interwoven web that generations of puppeteers and artisans have created with their skilled hands. Furthermore, by centering the relationship between puppets and the human body, the exhibition also underscores the idea that culture breathes life into objects, and, in return, these objects reflect and embody culture—the values, aesthetics, and experiential landscapes of the societies that create and perform them.

Upon entering the exhibition room, visitors are immediately drawn to a prominent display case containing thirty-four puppetry artifacts of varying shapes and sizes from different regions and cultures. The collection sets the tone of the exhibition by showcasing the diverse traditions and practices of puppetry art, such as a mermaid shadow puppet of Suphan Matcha, daughter of Ravana in the Thai and other Southeast Asian versions of Ramayana, a Belgian princess marionette, and an American glove puppet of an old lady, among others. At its center stands a striking six-legged potehi (布袋戲 glove puppetry) stage, once owned by the legendary puppet master Wang Yan (王炎, 1901–1993) of the Zhen Xi Yuan Puppetry Troupe (真西園), who was born during Taiwan’s Japanese colonial period and continued to thrive as a puppeteer after the war. This golden stage carries with it a poignant story: when an antique dealer attempted to purchase it at a low price to export to Japan, Dr. Paul Lin intervened, offering double the amount to ensure the artifact remained in Taiwan. Later, Wang Yan, whose vision had significantly deteriorated, was invited to confirm its authenticity. As he reached out and traced the familiar contours, worn smooth by years of performance, he recognized it instantly and began to weep.

Similar to the puppet stage, all featured puppets and objects exist in unique cultural and historical contexts, both in terms of their creation and performance and of how humans encounter and interact with them. In fact, the slogan “ouyu” (偶遇)is often referenced when promoting the exhibition. In Mandarin Chinese, ouyu means “to come across” or “to happen upon,” but ou as a single word also means “puppet.” The linguistic play of ouyu suggests “encountering puppets,” which highlights another theme of the exhibition: where and how people stumble upon puppets in everyday life. This also resonates with the exclamation of Dr. Paul Lin and the exhibition consultant Dr. Robin Ruizendaal, who is also the co-founder and former director of the Taiyuan Museum, that puppets always interact with humans and live beyond display cases.[1]

Throughout history, communities have turned to puppetry not only for entertainment but also as a means of confronting life’s uncertainties, seeking comfort amid misfortune, and expressing gratitude during prosperity. Puppeteers often seek the protection of theatrical deities, highlighting the spiritual dimensions of their craft. This connection is evident in the exhibition’s inclusion of sacred figures such as a statue and a string puppet of Marshal Tiandu, one of the most respected drama gods in Taiwan and China, a mask of the spiritual figure Ruesi from Thailand’s classical dance drama khon, and a statue of Myanmar’s deity, Lamaing Shin Ma, among others. These objects remind us that puppetry has long been intertwined with ritual, devotion, and the religious responsibilities of performance.

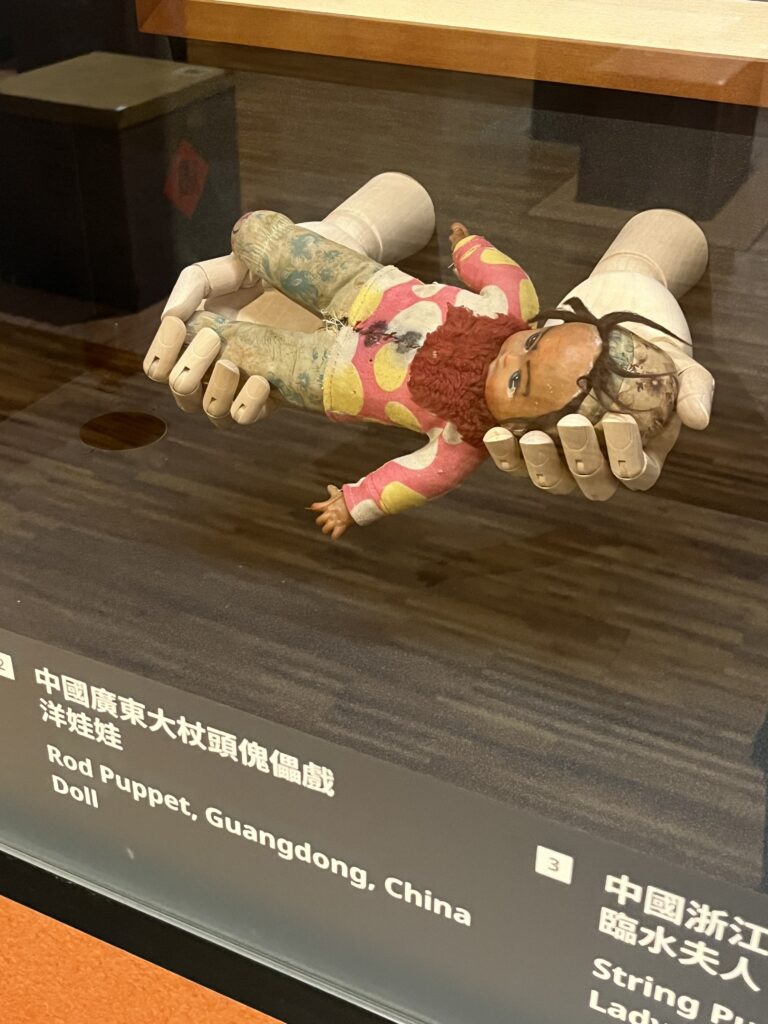

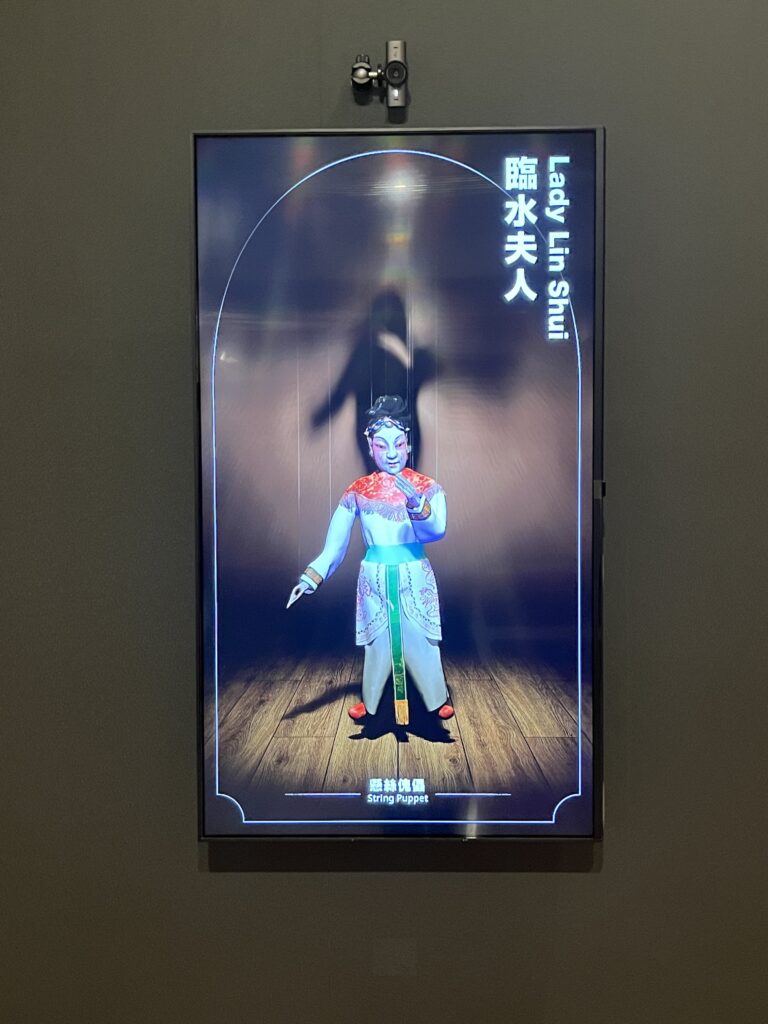

While many associate puppets with death and mourning, puppets also mark beginnings—birth, encounters with new lives, and expressions of hope. For example, in Chinese tradition, songzi (送子), “sending a child,” puppet rituals are performed to bless those hoping for children. Likewise, string puppet performances featuring Lady Lin Shui are often staged as prayers for a safe and smooth childbirth. One especially memorable piece on display is a small songzi doll used in rod puppet performances from Guangdong, China, and symbolizing a blessing for fertility. Displayed behind glass, the doll is gently cradled in a pair of sculpted hands, as if offered by the deities and placed into the arms of women longing for a child, like a cherished gift of hope. These practices reveal puppetry’s deep entanglement with life cycles, communal beliefs, and emotional anchoring.

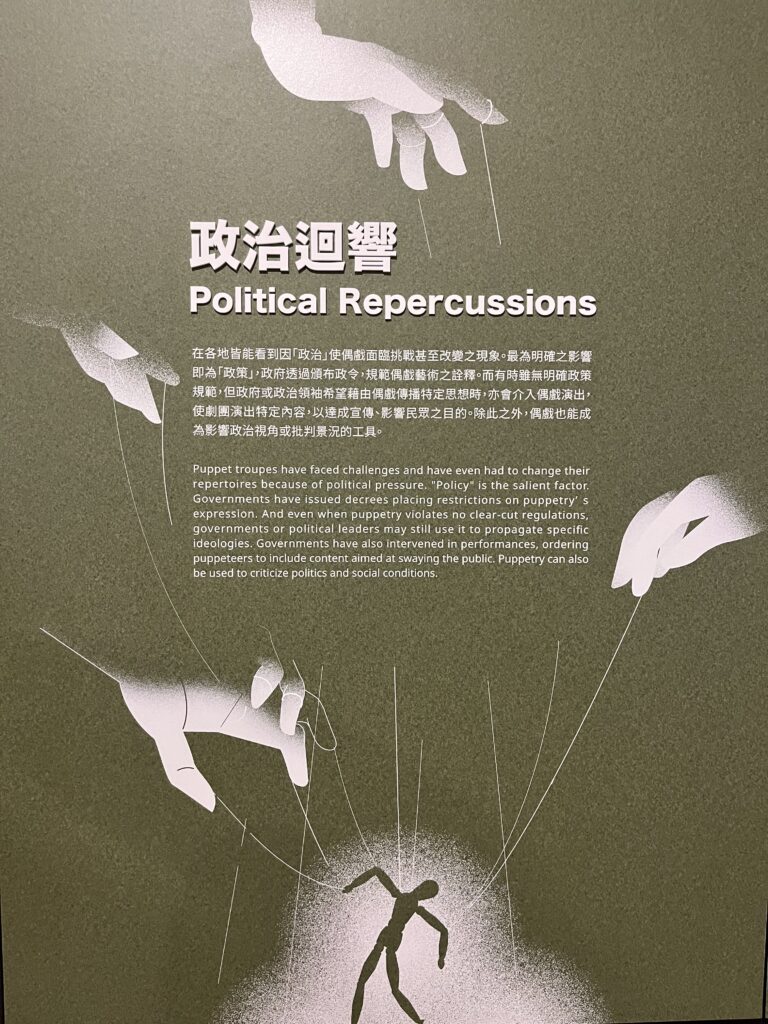

The human encounter with puppets certainly transcends customs and beliefs. In the section titled “Political Repercussions,” we see how puppet troupes have faced challenges due to policy changes, such as being subject to political surveillance or being forced to alter their repertoires. The visual of the wall text vividly depicts multiple hands manipulating a string puppet, a metaphor for external control. Wayang potehi puppetry was brought to Indonesia by immigrants from the Minnan region in the eighteenth century. However, during the Suharto regime (1967–1998), the government implemented an Indonesianization policy aimed at suppressing foreign cultures. Despite their attempts at self-censorship and removal of potentially undesirable content, potehi puppet troupes inevitably declined and did not make a comeback until later. Troupes began using local languages and costumes for performances, embracing the multicultural and ethnically diverse nature of the nation’s population.

While puppet shows may be shaped by policy, puppets have also been used for political propaganda. This exhibition features photographs of performances and shadow puppets used by the Chinese Communist Party to promote political messages during the Cultural Revolution in the 1970s. The shadow puppets wear military uniforms, and the shows feature characters such as male and female soldiers and farmers to convey political ideology. Interestingly, during a similar period in Taiwan, the “Anti-communist and Resisting Russian Cultural Promotion Train” toured the island with anti-communist puppet shows. Despite their different intentions, it is clear that puppetry is an effective tool for political purposes. One could also argue that tumultuous political environments cultivate and demonstrate the unique artistry and resilience of puppetry. In fact, heralding puppetry as a political mouthpiece provides a means to sustain art, tradition, and the livelihoods of those it reaches.

Puppetry has evolved in tandem with human society, shaped by the communities and contexts in which it lives. When different traditions and perspectives meet, sometimes harmoniously, sometimes in tension, new ideas emerge. The National Taiwan Museum acknowledges that simply placing puppets behind glass is not enough to sustain their spirit or significance, echoing the words of Dr. Lin and Dr. Ruizendaal. As more puppetry artifacts enter museum collections, they risk becoming static relics, disconnected from the living practices that once animated them. This exhibition demonstrates the museum’s commitment not only to preserving the physical objects, but also to showcasing the cultural environments and intangible heritage that give them life. Additionally, it invites new encounters and interactions by having actual puppets on-site and incorporating technological devices for visitors to play with. One interactive installation invites visitors to see their own bodies mirrored as puppets on screen, utilizing motion detection to animate virtual figures in real-time. As we move, the puppets move—responding, reflecting, and performing with us. In that moment of playful connection, the boundary between human and puppet blurs. We move together. We become each other’s doubles.

The final section of the exhibition features video interviews in which immigrants, expatriates, and new residents from various Asian countries share their encounters with and experiences of puppets from their cultures in Taiwan. They discuss how such exchanges enrich not only the collection but also the art of puppetry. These voices resonate with the spirit of the exhibition’s original title in Mandarin Chinese, Ou: Duoyuan wenhua zhi shen (偶:多元文化之身Multicultural Bodies of the Puppet): culture is what gives puppet bodies, while puppets also embody culture. In their capacity to carry memory, tradition, and transformation, puppets remind us that cultural heritage is never fixed. It moves, adapts, and grows, just like us.

Chee-Hann Wu

New York University

Notes

[1] National Taiwan Museum 2025, 00:02:13 and 00:03:38.

References

National Taiwan Museum 國立臺灣博物館. Puppetry Searching for Strange Jewelry Box: Taiyuan Asian Puppetry Museum. Posted April 30, 2025.

https://youtu.be/Mn3mtOA7kMs?si=M8Zv65fGVydrQf4I.